White Paper: Understanding Medicare Advantage Payment & Policy Recommendations 1

I. Overview

The rates paid to Medicare Advantage health plans are

determined annually through a bidding system that

is largely based on spending patterns in Traditional

Fee-For-Service (FFS) Medicare. It is imperative that

payments to Medicare Advantage health plans are

accurate, adequate and stable to allow them to provide

the necessary care to their enrollees, and to continue

to innovate in new care models and service oerings.

This White Paper provides an in-depth explanation of

the Medicare Advantage payment system, discusses

current challenges and limitations of the payment

system, and proposes several policy recommendations

to ensure consistent and stable payments in Medicare

Advantage.

Understanding Medicare Advantage

Payment & Policy Recommendations

WHITE PAPER SEPTEMBER 2018

TABLE OF CONTENTS:

I. Overview

II. Background on Medicare

Advantage

a. General Overview

b. Rate & Policy Updates:

Annual Rate Notice and

Call Letter

c. Beneficiary Enrollment

& Access

d. Types of Medicare

Advantage Plans

e. Overview of Medicare

Advantage Quality Star

Rating System

f. Medicare Advantage

& Traditional Fee-for-

Service (FFS) Medicare

III. Components of Medicare

Advantage

a. Base Rate

b. Risk Adjustment

c. Premiums

d. Rebates

e. Timeline of Key

Payment Policy

Milestones

IV. Current Challenges &

Policy Recommendations

BMA POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS TO ENSURE

PAYMENT CONSISTENCY AND STABLITY:

1. Reduce frequency of major payment policy

changes;

2. Improve the risk adjustment model and process;

3. Improve the accuracy of the benchmark

calculation; and

4. Reward quality by eliminating the benchmark

cap for plans with 4+ stars.

White Paper: Understanding Medicare Advantage Payment & Policy Recommendations 2

II. Background

A. General Overview

Medicare Advantage, also called Part C, is an option within Medicare that allows Medicare-

eligible seniors and beneficiaries with disabilities to receive their benefits through a private

plan of their choice, instead of receiving coverage through Traditional Fee-For-Service

(FFS) Medicare. Medicare Advantage plans are approved and regulated by the Centers for

Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). The Federal government, through CMS, pays Medicare

Advantage plans a fixed (or capitated) monthly amount per beneficiary to provide health

benefits to an enrolled individual. Medicare Advantage plans provide all Medicare Part A

and Part B services, excluding hospice. Plans have the option to oer prescription drug

coverage under Medicare Part D, which is funded through a separate bidding and payment

system.

B. Rate & Policy Updates: Annual Rate Notice and Call Letter

Medicare Advantage payment methodology and rates, as well as other policies governing

the Medicare Advantage program, are modified and updated each year. The Social Security

Act requires the Secretary of Health and Human Services to make an annual announcement,

called the Rate Notice and Call Letter, of these changes no later than the second Monday in

April before the calendar year in which the changes will be made.

1

The Social Security Act

further requires the Secretary to publish an Advance Notice and Draft Call Letter at least

60 days before publication of the Final Rate Notice and Call Letter, providing stakeholders

an opportunity to comment on proposed changes to the Medicare Advantage program. In

addition, the Secretary also issues an Early Preview of the Rate Notice in late November or

early December before the Advance Notice.

C. Beneficiary Enrollment & Access

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid

Services (CMS) reports that 20 million

beneficiaries – or more than a third of the more

than 59 million eligible Medicare beneficiaries

– are enrolled in Medicare Advantage in 2018,

more than double the 9.7 million that were

enrolled in 2008.

2

The Congressional Budget

Oce estimates that Medicare Advantage

enrollment will grow to more than 30 million

individuals over the next 10 years.

3

While enrollment in Medicare Advantage

continues to grow, substantial geographic variation in enrollment exists. Medicare

Advantage enrollment rates at the state level range from a low of 2% in North Dakota to a

BMA’s Medicare Advantage

Enrollment Map provides

Medicare Advantage

enrollment information

at the county and

Congressional district level.

White Paper: Understanding Medicare Advantage Payment & Policy Recommendations 3

high of 44% in Oregon.

4

This variation is due to many factors, including long-term insurance

market factors in states as well as specific characteristics of each state – for example,

low penetration rates due to a state being rural and sparsely populated (e.g. Vermont,

Wyoming), high penetration rates due to a concentration of retirees (e.g. Florida, Arizona),

or a large number of hospital-owned plans (e.g. Minnesota, Oregon).

Beneficiary access to Medicare Advantage is strong. In 2018, Medicare Advantage included

2,317 individual plan options.

5

In total, 99% of all Medicare beneficiaries have access to a

Medicare Advantage plan and most beneficiaries have multiple plans to choose from in their

area.

6

A recent analysis found that 90% of Medicare Advantage beneficiaries have a choice

of at least five Medicare Advantage plan options, 71% have at least 10 plans options, and

55% have at least 15 plan options.

7

More than 80% of all beneficiaries have access to at least

one zero premium plan, and 40% of beneficiaries are enrolled in a zero premium plan.

D. Types of Medicare Advantage Plans

Medicare Advantage plans oer coordinated care, typically organized around a network of

health care providers that works to manage enrollees’ care. Each Medicare Advantage plan

establishes its own network of providers, subject to legislative and regulatory requirements

that determine the number and type of providers that must be included in a plan’s service

area.

The types of Medicare Advantage plans available to beneficiaries are:

1. Health Maintenance Organizations (HMOs): HMOs often require members to choose a

primary care physician to coordinate their care and utilize network providers or pay the

full cost of care received outside the network. Generally, HMOs require a referral from

a primary care physician to see a specialist. In 2018, more than 60% of enrollees are in

HMOs.

8

2. Preferred Provider Organizations (PPOs): PPOs are similar to HMOs, but they may not

require members to select a primary care physician, and they often do not require a

referral to see a specialist. They may oer coverage for health care services received

outside the network, but typically require members to pay a larger portion of the cost of

out-of-network care. PPOs may be local (county-specific) or regional (span two or more

states). In 2018, approximately 34% of enrollees are in PPOs.

9

3. Private Fee-For-Service (PFFS): PFFS plans allow enrollees to see any Medicare-eligible

health care provider who accepts payment from that plan; however, they may oer

members financial incentives to use certain providers. Just 1% of Medicare Advantage

enrollees selected a (PFFS) plan. In 2018, less than 1% of enrollees are in PFFS plans.

10

4. Special Needs Plans (SNPs): SNPs are a type of Medicare Advantage plan tailored to

serve frail, disabled, and chronically-ill beneficiaries. There are SNPs tailored to enrollees

who are dually eligible for both Medicare and Medicaid, those who have a severe or

disabling chronic condition, or those who live in a nursing home or who require skilled

White Paper: Understanding Medicare Advantage Payment & Policy Recommendations 4

nursing care at home. In 2018, approximately 13% of Medicare Advantage members are

enrolled in SNPs.

11

5. Employer Group Waiver Plans (EGWPs): EGWPs are a type of Medicare Advantage plan

oered by an employer to its retiree population. In 2018, approximately 20% of Medicare

Advantage members are enrolled in EGWPs.

12

E. Overview of Medicare Advantage Quality Star Rating System

Medicare Advantage plans are awarded a star rating between one and five based on

performance on certain quality measures in the Medicare Advantage Quality Star Rating

System. The Star Rating System plays a critical role in ensuring public accountability and

enhancing consumer choice by providing quality information on plans. Star ratings foster

competition between plans to improve quality and may lead to quality-based financial

incentives for some plans and providers. In 2018, 73% of Medicare Advantage enrollees are

enrolled in high-performing four- or five-star plans, almost quadruple the percent of those

enrolled in high-performing plans in 2009.

F. Medicare Advantage & Traditional Fee-for-Service (FFS) Medicare

The financial framework in Medicare Advantage supports care delivery that focuses on

care management, integrated care models, and early interventions. Because Medicare

Advantage plans receive a capitated (fixed) monthly payment per beneficiary to provide

health benefits to enrollees, the plan is at-risk if costs for an enrollee exceed the capitated

payment (plus enrollee cost-sharing). At the same time, if costs are less than the capitated

payment (plus enrollee cost-sharing), plans retain the savings.

The capitated payment structure aligns plan financial incentives with patient health

outcomes, motivating Medicare Advantage plans to oer care coordination as well as

preventive services, early interventions and other services that help enrollees stay healthy

and avoid unnecessary, costly health care services, such as emergency room visits and

hospital admissions. In addition, as described in detail below, if a plan receives rebates from

CMS, it must use those funds to reduce enrollee out-of-pocket costs or to provide additional

supplemental benefits, such as dental or vision coverage.

Payments to Medicare Advantage plans are based on FFS Medicare. As detailed below,

Medicare Advantage payments are largely based on average FFS Medicare spending in

individual counties across the country.

White Paper: Understanding Medicare Advantage Payment & Policy Recommendations 5

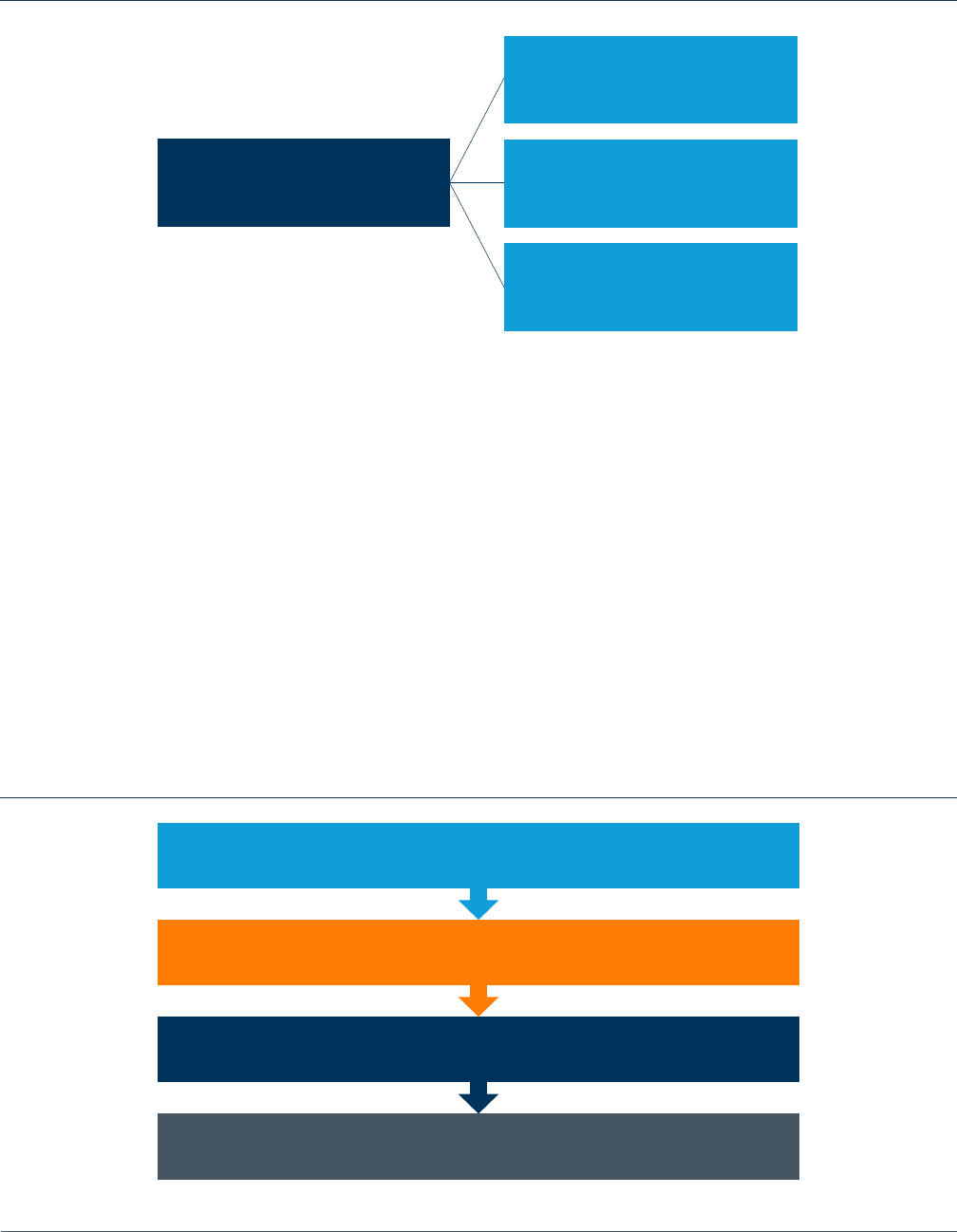

III. Components of Medicare Advantage Payment

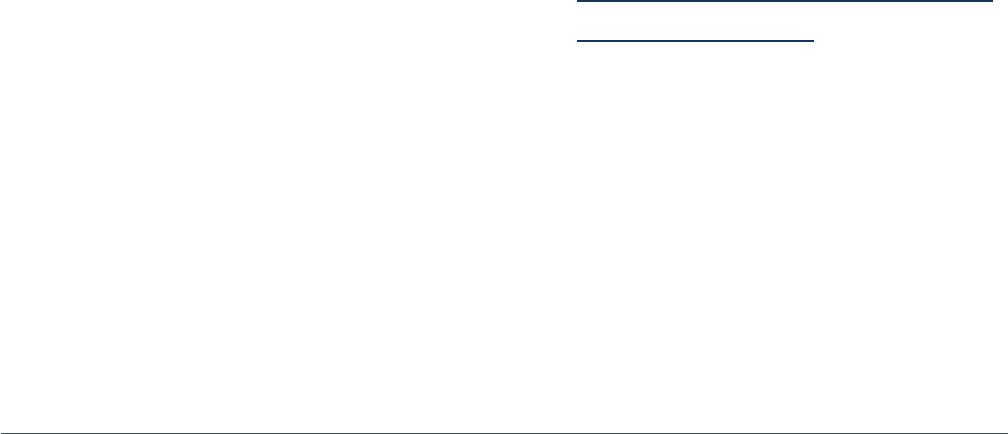

There are four key components that together determine what Medicare Advantage health

plans are paid to provide care for their enrollees:

• Base rate. The base rate is the lesser of the plan’s bid or the benchmark rate. If a plan’s

bid is below the benchmark, then the base rate equals the plan’s bid. If a plan’s bid is

above the benchmark, then the base rate equals the benchmark.

• Risk adjustment. The base rate for a particular enrollee is then adjusted to reflect that

enrollee’s risk score.

• Premiums. Plans that bid below the benchmark may not charge any enrollee premium.

Plans that bid above the benchmark charge a premium that is equal to the dierence

between the bid and the benchmark.

• Rebates. Plans that bid below the benchmark receive a rebate equal to a percentage of

the dierence between the benchmark and the bid.

Each of these components are described in greater detail below.

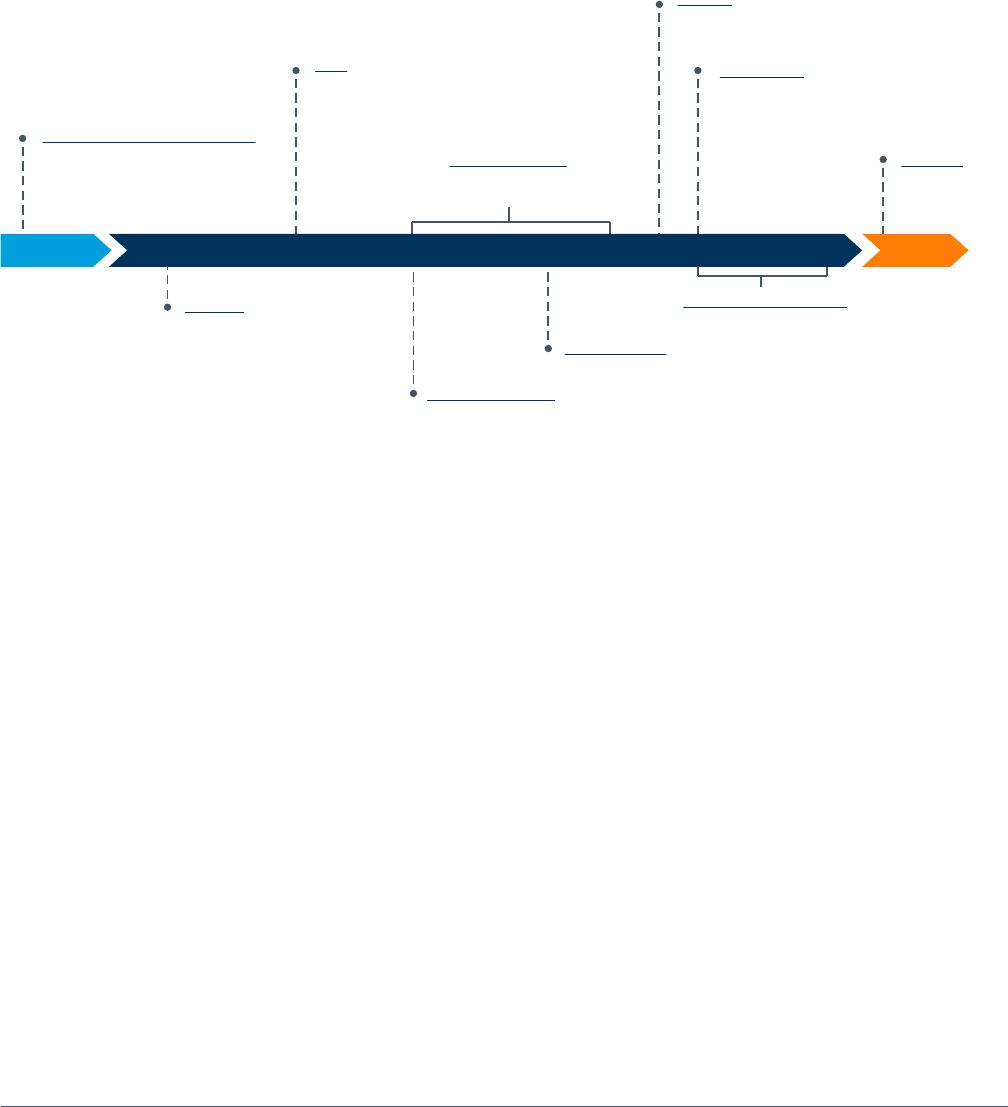

FIGURE 1: SUMMARY OF MEDICARE ADVANTAGE PAYMENT

Base Rate

=

Standard

Bid

Risk Adjustment

Plan Bid

Below

Benchmark

Plan Bid

Not Below

Benchmark

CMS-HCC CMS-HCC

Enrollee

Basic Premium

Always 0

Payment

to Plan

Payment

to Plan

Rebate = 0.5 to 0.7

varies by plan star rating

x

risk adjusted

benchmark-actual bid

Patient characteristics:

Diagnoses, Sex, Working aged status, Age,

Medicaid status, Disabled status

Adjustment (if any) to

CMS payment for risk

model factors of individual

enrollees to maintain fixed

enrollee premium

Enrollee

Basic Premium

Equal to the

Dierence between

the bid and the

benchmark

Base

Rate

CMS-

HCC

Risk

Score

Base Rate

=

Benchmark

x

=

=

+

+

–

+

+

ŧ

ŧ

ŧ

ŧ

ŧ

ŧ

Source: MedPAC. “Medicare Advantage Payment System Basics.” October 2016. Available at: http://medpac.gov/docs/

default-source/payment-basics/medpac_payment_basics_16_ma_final.pdf?sfvrsn=0

White Paper: Understanding Medicare Advantage Payment & Policy Recommendations 6

A. Base Rate

The first component of the payment to a Medicare Advantage plan is the base rate. The

base rate is determined by the relationship between the county-level benchmark and the

plan bid. First, CMS determines the average FFS Medicare spending in each county, which,

following adjustments for geography and demographics, becomes the benchmark. Second,

Medicare Advantage plans bid to provide coverage in a county. Finally, CMS compares each

plan’s bid to the benchmark. The base rate is the lower of the plan’s bid or the benchmark.

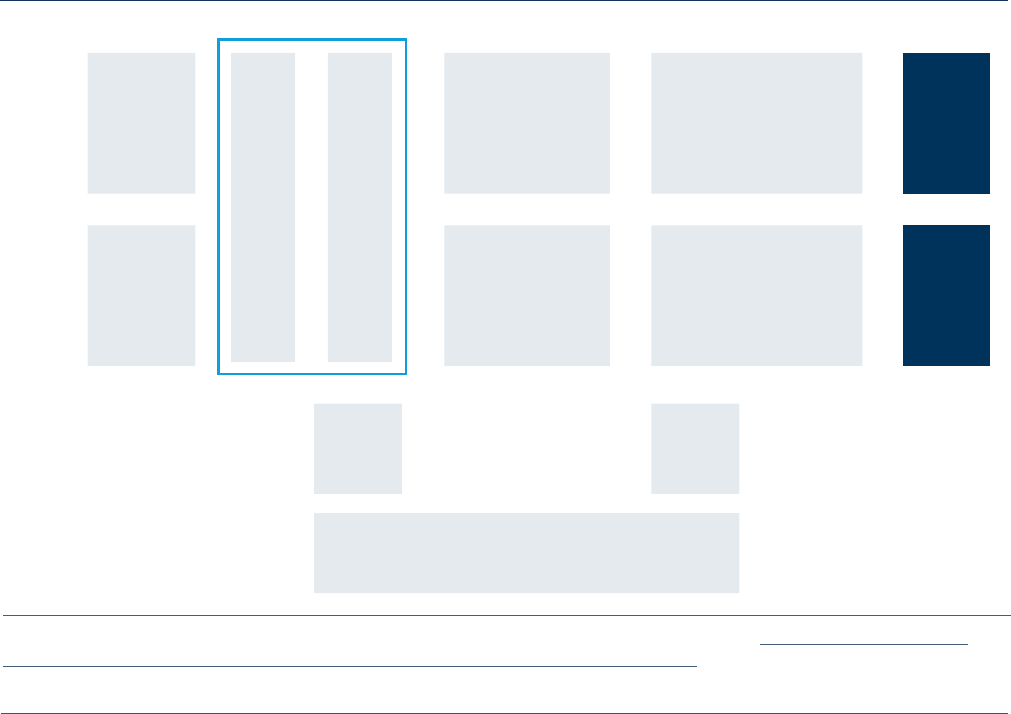

FIGURE 2: HYPOTHETICAL BID AND BENCHMARK SCENARIOS

1. Benchmarks

i. Benchmarks Defined

Benchmarks are the targets against which plans bid to provide coverage of Medicare Part

A and Part B services. A separate benchmark is calculated for each county in the United

States and is set as a percentage of average FFS Medicare spending per beneficiary. This

means that Medicare Advantage benchmark levels in each county are based on the practice

patterns of physicians and other providers who bill FFS Medicare.

For payment purposes, Medicare Advantage plans fall under one of two categories: local

plans or regional plans. Local plans may be any type of plan (HMO, PPO, PFFS) and may

serve beneficiaries living in one or more counties. Regional plans must be PPOs and serve

all of one of the 26 regions established by CMS.

Establishing the benchmarks for both local and regional plans requires a determination

of per capita FFS Medicare spending for each county. To make this determination, the

Secretary first projects the national estimated FFS Medicare per capita costs for the

following year ($848.21 per month for 2018).

13

This amount is then multiplied by a county-

specific geographic index, which is based on a five-year rolling average of FFS Medicare

Benchmark = $1,000

Plan Bids above Benchmark

Plan bid=$1,100

Plan payment from CMS = $1,000

Plan Bids above Benchmark

Plan bid=$1,100

Plan payment from CMS = $1,000

Plans that receive 4 or 5

stars are eligible to receive

a higher rebate percentage

Rebate amount = $50

Beneficiary preimium for

Part A/B services = $100

CMS savings = $50

White Paper: Understanding Medicare Advantage Payment & Policy Recommendations 7

spending in the county, weighted for enrollment and average risk scores, to yield the per

capita FFS Medicare spending amount for each county.

ii. County-Level Benchmark Calculation: Local Plans

To determine the county-level benchmarks for local plans, the per capita FFS Medicare

spending amount is adjusted based on the county’s historical costs relative to the rest of

the nation. Counties with the lowest FFS Medicare spending receive the highest percentage

of per capita FFS Medicare spending as their benchmark. These percentage adjustments

were established by the Aordable Care Act as follows:

Highest-cost quartile 95% of FFS costs

Second-highest cost quartile 100% of FFS costs

Third-highest cost quartile 107.5% of FFS costs

Lowest-cost quartile 115% of FFS costs

For a local Medicare Advantage plan that operates in more than one county, an average

benchmark is calculated across the counties in which the plan operates, weighted by

enrollment.

iii. County-Level Benchmark Calculation: Regional Plans

The process for calculating benchmarks for regional plans, which must serve all of at

least one of the 26 regions established by CMS, is a bit more complex. These regional

benchmarks are a weighted average of:

• the average county-level benchmark (described above), weighted by the number of

Medicare beneficiaries in each county and the national percentage of beneficiaries

in FFS Medicare, and

• the average plan bid, weighted by each plan’s projected enrollment and the national

percentage of beneficiaries in Medicare Advantage.

14

iv. Quality Adjustments to Benchmarks

Benchmarks for both local and regional Medicare Advantage plans are also adjusted based

on plan quality. Plans with a 4, 4.5, or 5-star quality rating from CMS receive an increase in

their benchmark (5% in 2018).

15

In addition, these benchmark quality adjustments may be

doubled for high-quality plans in certain qualifying counties (urban areas with FFS Medicare

spending below the national average and historically high rates of enrollment in Medicare

Advantage).

White Paper: Understanding Medicare Advantage Payment & Policy Recommendations 8

v. Benchmark Caps

In many counties across the country, benchmarks (including quality adjustments) are

capped at their pre-ACA levels. In 2017, benchmarks in half of counties across the country

were constrained in some way by the benchmark cap, meaning plans with 4 or more stars

received a benchmark quality bonus less than the statutory 5% or received no quality bonus

at all.

16

In 2016, more than 2 million Medicare beneficiaries were enrolled in 4-star plans but

denied enhanced benefits, including reduced cost-sharing, because of the benchmark cap.

2. Plan Bids

With benchmarks determined, the next step in the payment process is the submission of

plan bids. Medicare Advantage plans submit bids reflecting the plan’s estimated cost of

providing all Medicare Part A and Part B services to a beneficiary with “average” health,

with the exception of hospice. Bids include the estimated costs of medical services as well

as administrative expenses and profit. However, plan administrative expenses and profit may

not exceed 15% of total plan revenue, ensuring that 85% of revenue is dedicated to member

benefits. Plans that do not meet this minimum medical loss ratio (MLR) requirement must

refund CMS the dierence between their MLR and 85%.

Medicare Advantage plans that wish to oer Part D prescription drug benefits submit a

separate bid for the Part D portion of coverage. Payment for Part D-covered services is

calculated separately, in the same manner as it is for plans oering standalone prescription

drug coverage.

3. Calculation of the Base Rate

A Medicare Advantage plan’s base rate is determined by comparing the plan’s bid and the

benchmark. If the plan’s bid is below the benchmark, the bid becomes the plan’s base rate.

If the plan’s bid is at or above the benchmark, then the benchmark becomes the plan’s

base rate, and the dierence is returned to enrollees in the form of reduced cost sharing

obligations or enhanced benefits.

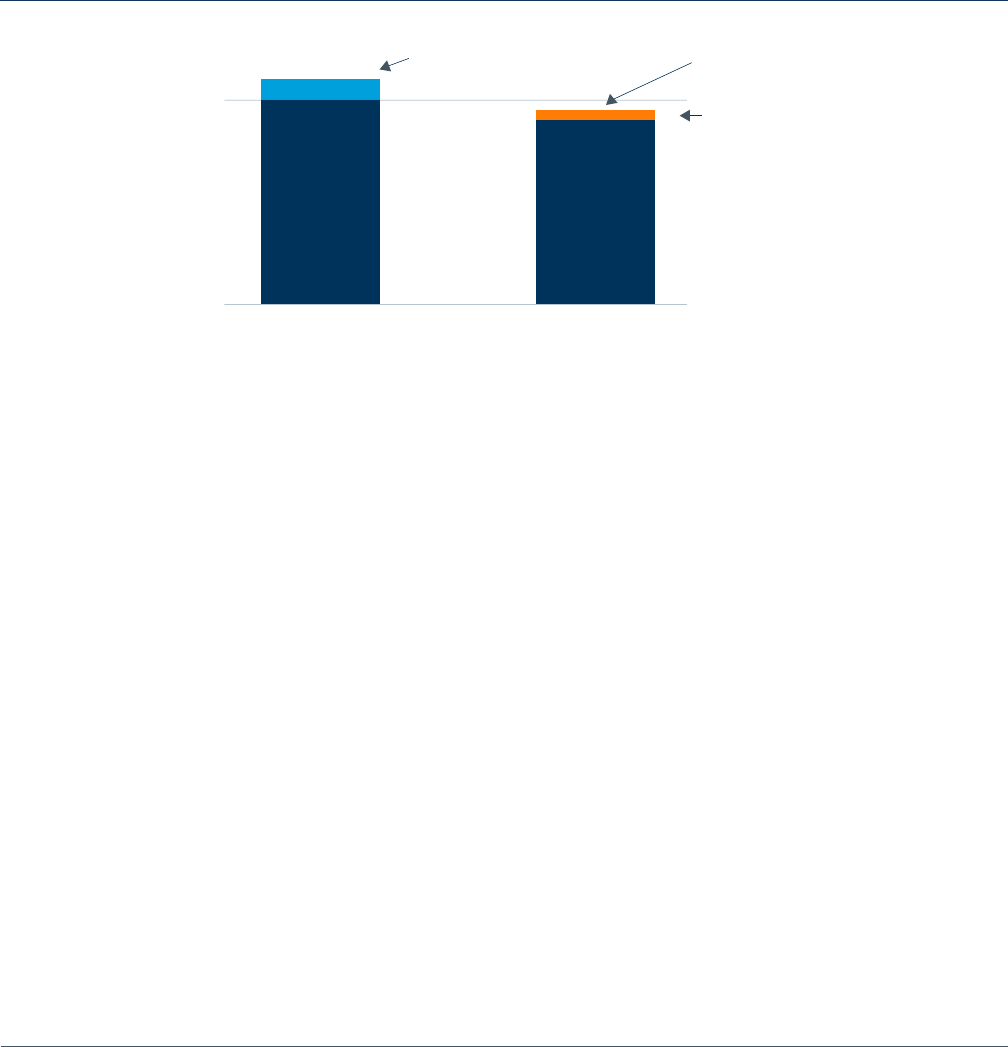

B. Risk Adjustment

After the base rate is determined, CMS uses a system called “risk adjustment” to modify

a plan’s base rate to reflect the health status of each enrollee. This ensures capitated

payments made to Medicare Advantage plans reflect the expected cost of providing health

care to each beneficiary.

17

A risk score of 1.0 implies that the person’s expected costs are

equal to the costs of a beneficiary of average health. An enrollee with a risk score of 2.0 is

expected to cost twice as much as the average, whereas an enrollee with a risk score of 0.5

is expected to cost 50 percent less than average (see Figure 3).

White Paper: Understanding Medicare Advantage Payment & Policy Recommendations 9

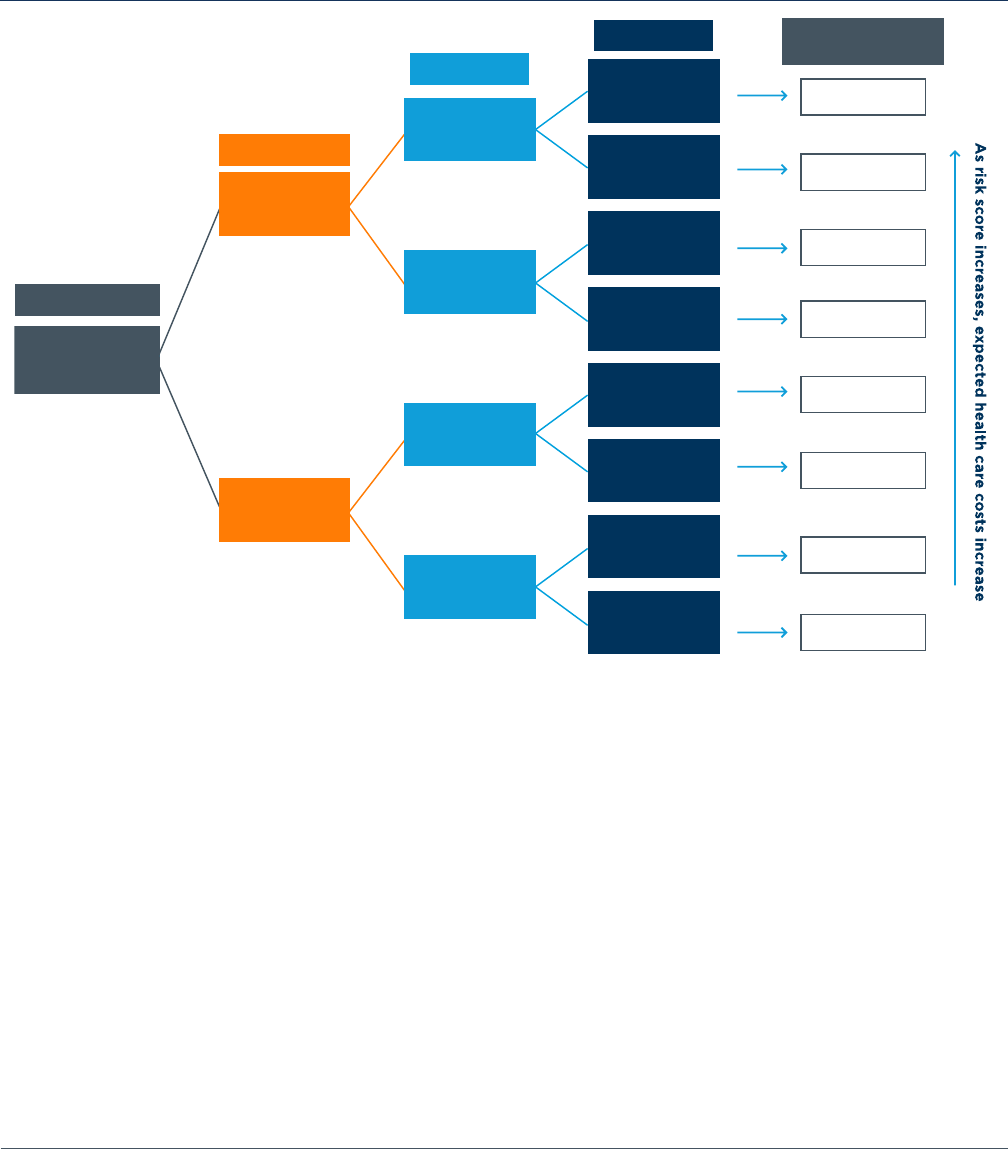

FIGURE 3: INDIVIDUAL RISK SCORES

Since 2004, CMS has used the Hierarchical Condition Categories (CMS-HCC) model to

risk adjust Medicare Advantage base rates. The CMS-HCC model uses diagnoses from

inpatient, outpatient, and physician encounters to provide a comprehensive accounting

for the full range of patient spending. To generate a risk score, CMS first groups all

International Classification of Disease, Tenth Edition (ICD-10) codes into diagnostic

groups called DxGroups. These groups include diagnosis codes that cover similar medical

conditions. Second, CMS combines the DxGroups into Condition Categories (CCs), which

groups enrollees based on similar clinical profiles and expected costs. Third, CMS imposes

hierarchies on the model by dropping a less severe manifestation of the disease if a more

severe manifestation is present. Finally, once the hierarchies are applied, CMS publishes the

list of categories, or Hierarchical Condition Categories (HCCs), as part of the annual rate

announcement, typically located in a table in a supplemental attachment. This process is

illustrated in Figure 4 below.

FIGURE 4: MEDICARE ADVANTAGE RISK ADJUSTMENT PROCESS BEGINS BY GROUPING DISEASES AND ASSIGNING HCCS

Group ICD-10 codes into DxGroups that represent a medical condition

Combine DxGroups into Condition Categories that are similar clinically

and in terms of cost

Impose hierarchies so that person only is coded with most severe

manifestation of disease

Select HCCs to include for payment

Risk Score = 0.5

Expected costs are 50% lower than

Costs for the average beneficiary

Risk Score = 1.0

Expected costs are equal to

Costs for the average beneficiary

Individual Risk Scores Assess

Relative Health Care Costs

Risk Score = 2.0

Expected costs are two times higher

Than costs for the average beneficiary

White Paper: Understanding Medicare Advantage Payment & Policy Recommendations 10

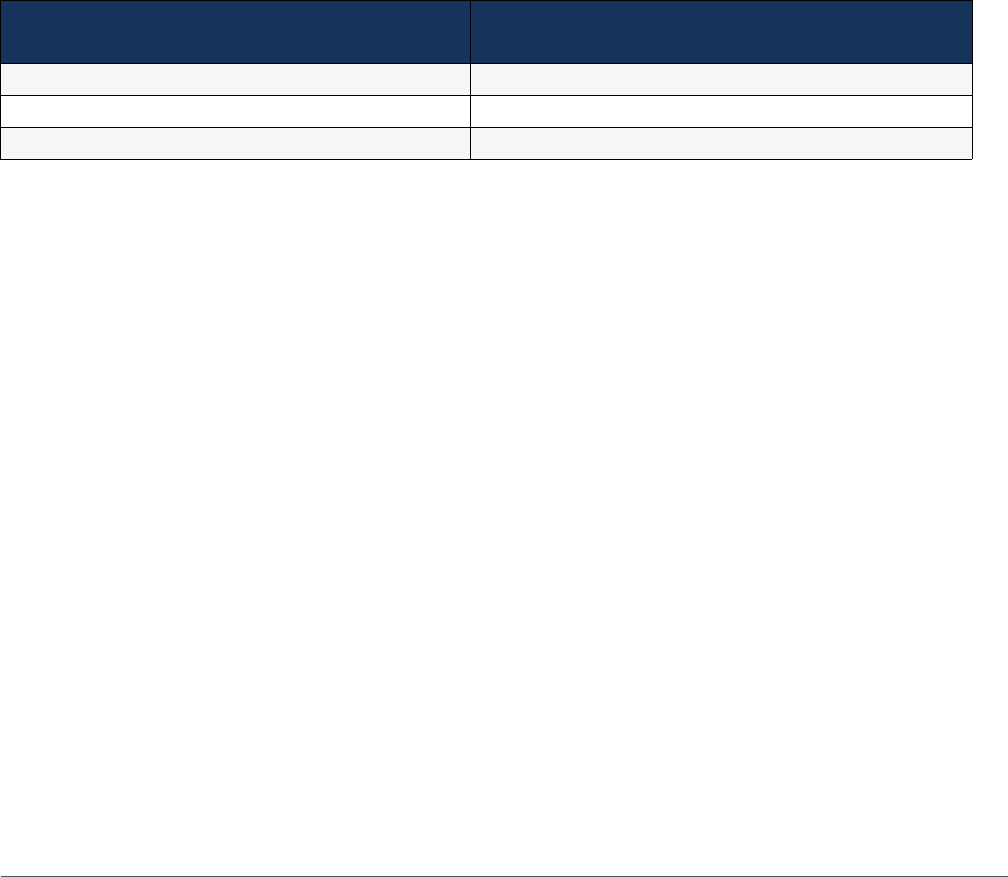

Each HCC has an associated coecient (or weight). The coecients for each HCC are

added, along with those for age and gender, to determine the risk score, as shown in Figure

5.

18

CMS estimates the costs associated with dierent risk scores based on FFS Medicare

spending and utilization data.

FIGURE 5: MEDICARE ADVANTAGE RISK ADJUSTMENT EXAMPLE

Because CMS uses FFS Medicare data to calculate payments to Medicare Advantage plans,

it also must adjust those payments to account for coding pattern dierences that exist

between Medicare Advantage and FFS Medicare. These coding dierences arise from

structural, payment, and care model dierences between FFS Medicare and Medicare

Advantage. For instance, because CMS uses diagnosis codes submitted by providers to

risk-adjust plan payments, Medicare Advantage plans have an incentive to ensure accuracy

in diagnosis codes both to ensure adequate payment to meet beneficiary needs and to

identify at-risk individuals for early intervention and care management. FFS Medicare does

not require the same specificity in diagnosis coding because payments to providers rely

on procedure codes. To account for this dierence, Congress mandated an annual coding

intensity adjustment in 2010 and subsequent years which requires CMS to reduce Medicare

Advantage risk scores by a uniform, pre-determined factor every year. As of 2018, the

reduction is 5.91% annually. CMS has the statutory authority to increase the annual coding

intensity adjustment but, to date, has not used that authority.

Age and Gender

HCC 111

HCC 86

HCC 88

1.149

1.009

0.916

0.776

0.821

0.681

0.588

0.448

Normalized

Risk Score

Female beneficiary,

age75

(0.448)

COPD

(0.328)

Acute Myocardial

Infarction

(0.233)

Angina Pectoris

(0.140)

Angina Pectoris

(0.140)

Angina Pectoris

(0.140)

Angina Pectoris

(0.140)

No Angina Pectoris

No Angina Pectoris

No Angina Pectoris

No Angina Pectoris

No Acute

Myocardial

Infarction

No Acute

Myocardial

Infarction

Acute Myocardial

Infarction

(0.233)

No COPD

White Paper: Understanding Medicare Advantage Payment & Policy Recommendations 11

C. Premiums

The third component of payment to a Medicare Advantage plan is the enrollee premium.

Depending on how a plan’s bid compares to the benchmark, the plan may charge enrollees

a monthly premium. If a plan bids above the benchmark, then the enrollee pays a premium

equal to the dierence between the bid and the benchmark. If a plan bids below the

benchmark, there is no member premium.

D. Rebates

The fourth and final component of the payment to a Medicare Advantage plan is the rebate.

All plans that bid below the benchmark receive a percentage of the dierence between the

bid and benchmark as a rebate, ranging from 50% to 70% of the dierence between the bid

and the benchmark. The amount of the rebate paid to the plan is determined by the plan’s

quality star rating; plans with higher star ratings receive Quality Bonus Payments (QBPs) in

the form of a higher percentage of the dierence as a rebate, as follows:

Plan Quality Star Rating

Percent of Bid-Benchmark Dierence

Paid to Plan as a Rebate

3 Stars or fewer 50%

3.5 - 4 Stars 65%

4.5 - 5 Stars 70%

Plans are required to use rebates and QBPs to provide supplemental benefits, such as

hearing, dental or vision, to reduce beneficiary cost-sharing, or to provide innovations in

care delivery, such as telemedicine or home care. The combination of zero premiums and

additional benefits incentivizes Medicare beneficiaries to select high-quality, lower-cost

Medicare Advantage plans.

White Paper: Understanding Medicare Advantage Payment & Policy Recommendations 12

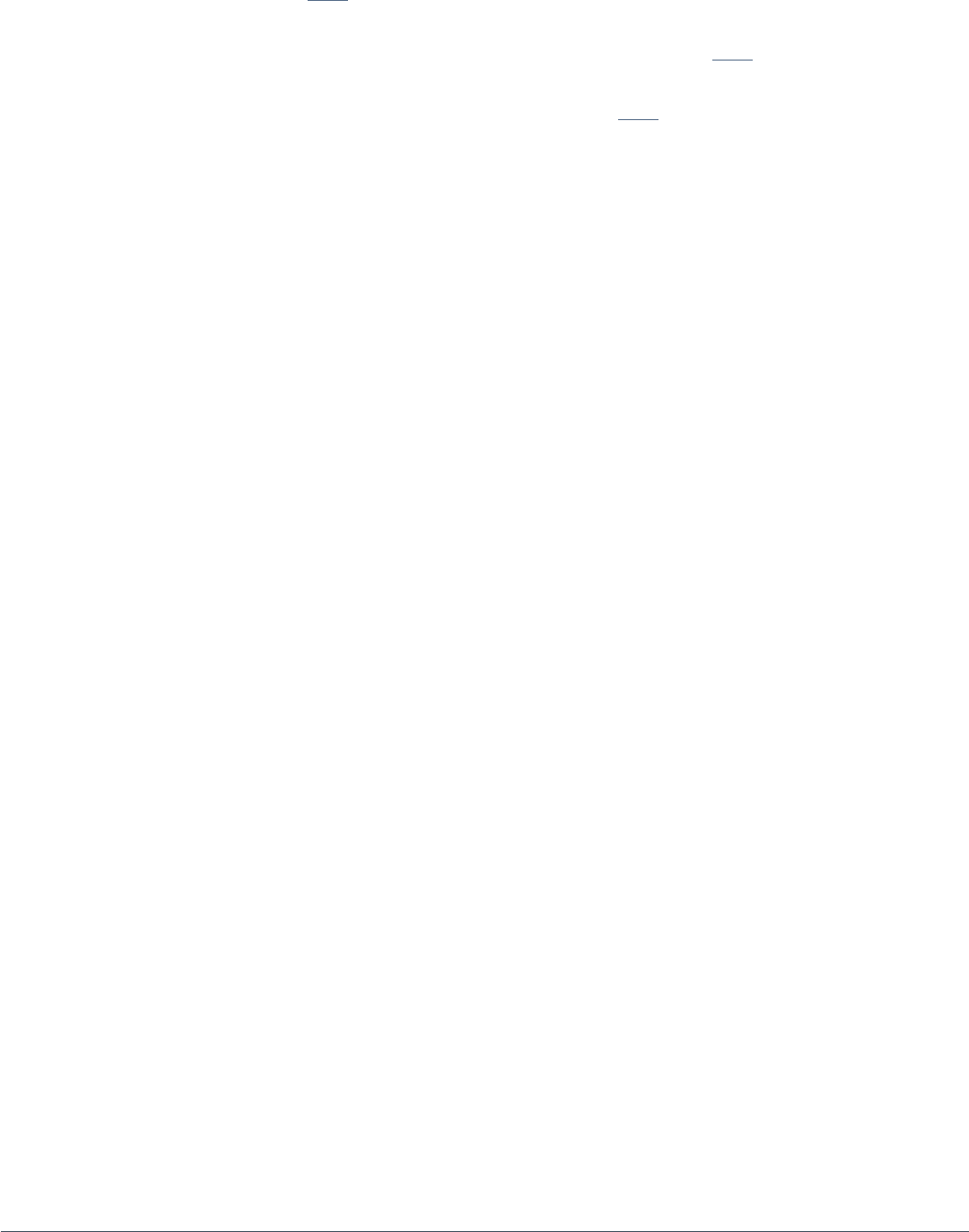

E. Timeline of Annual Payment Policy Milestones

Benchmark development, bid submission, and determination of each plan’s payment is a

lengthy process with many steps, identified below.

19

November (of the previous year)

CMS releases an early preview of

rates for the following plan

payment year

February

CMS publishes Advance Notice

and Draft Call Letter with a

30-day comment period

April

CMS publishes Final Rate Notice

and Call Letter for the following

plan payment year

June - September

CMS reviews and approves bid

data; Actuarial certifications due

June (first Monday)

Medicare Advantage

plans submit bids

Mid-October

Medicare Advantage

plan quality star ratings

for following payment

year announced

October 15 - December 7

Open Enrollment

Mid-September

Contracts fully executed

October

Medicare Advantage plans

may begin marketing

January 1

Plan Benefit

Period Begins

White Paper: Understanding Medicare Advantage Payment & Policy Recommendations 13

IV. Current Challenges & Policy Recommendations

There are challenges in the Medicare Advantage payment system that potentially

undermine the consistency and stability of payment and may impact the resources

available to care for beneficiaries and to invest and innovate in new models to improve

care delivery and contain costs. To address these challenges, BMA makes the following

recommendations:

1. Reduce frequency of major payment policy changes

Challenge. As noted above, CMS issues an Advance Notice of Methodological Changes

and Draft Call Letter each year in February and finalizes these proposed changes each

April. Through this annual rate setting process, CMS may change any or every element

of Medicare Advantage payment rates, including changes to the risk adjustment model,

Star Ratings system, and other factors that significantly influence payment rates. Plans

operating in this unpredictable and unstable rate setting environment must prepare for

unstable funding and unforeseen rate cuts, which may not be aligned with multi-year

contracts between plans and multiple providers, including value-based contracts. This

unpredictability impacts eorts to make investments in innovation and care delivery

programs that better meet the needs of Medicare Advantage enrollees and may negatively

impact beneficiary cost sharing reductions or enhanced benefits.

Policy Recommendation. To bring some stability to the rate setting process, BMA

encourages CMS to consider a multi-year process for Medicare Advantage payment policy

changes. Using a multi-year process will help streamline and alleviate unnecessary burdens

in the regulatory process, provide predictability to Medicare Advantage plans so they may

invest in innovation and care improvements, encourage multi-year value-based contracting

that includes multi-year goals regarding risk-assumption by the provider, and reduce

administrative burdens on health care providers. A multi-year policy change process would

also bring stability to plans’ community partners that are asked to build workforce and

administrative infrastructure. In a multi-year policy setting process, CMS would be able to

spread policy changes over a multi-year cycle while continuing to make annual rate updates

required by statute.

BMA POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS TO ENSURE PAYMENT CONSISTENCY AND STABLITY:

1. Reduce frequency of major payment policy changes;

2. Improve the risk adjustment model and process;

3. Improve the accuracy of the benchmark calculation; and

4. Reward quality by lifting the benchmark cap.

White Paper: Understanding Medicare Advantage Payment & Policy Recommendations 14

2. Improve the risk adjustment model and process

Challenge. CMS has changed the risk adjustment model over the past several years in an

eort to improve payment accuracy.

20

However, challenges remain both in terms of the

model itself and the process for making further changes. While changes in the model

to improve accuracy and adequacy of payment to meet beneficiary needs are essential,

the stability of the model is also critical. Any changes to the risk adjustment model are

dicult for stakeholders, including clinicians, to understand, assess, and implement. These

challenges are amplified when stakeholders have limited information regarding the impacts,

consequences, or concerns about both the current model and proposed changes.

In addition to challenges with the coding intensity adjustment, described above, several

structural challenges exist within the risk adjustment model. First, CMS has found that the

current risk model underpays Medicare Advantage plans for coverage provided to dual-

eligible beneficiaries, who are among the most high-need, high-cost, high-risk enrollees

and require more specialized care and management. Second, stakeholders continue to have

concerns regarding the risk model’s ability to accurately predict costs for individuals living

with multiple chronic conditions.

Third, stakeholders have raised serious concerns about the transition to the Encounter

Data System (EDS) as the single source of enrollee diagnosis data used as the basis for risk

scores. These concerns were recently echoed by the Government Accountability Oce,

which concluded that limited progress has been made to validate the EDS, potentially

resulting in inaccurate risk scores.

21

CMS is transitioning the system used to gather diagnosis

codes and is currently using a blended version of two dierent systems. Under the current

system, Medicare Advantage plans filter diagnosis codes and submit them to CMS, where

the files are reviewed and audited for accuracy. With the newer EDS, Medicare Advantage

plans submit all unfiltered data directly to CMS, which then applies its own filtering logic to

extract diagnosis codes.

Policy Recommendations.

1

A well-functioning risk adjustment program must adequately

pay plans that enroll high-cost individuals and manage their care eectively. With millions

of baby boomers aging into Medicare, it is essential that risk adjustment in Medicare

Advantage provides for adequate payment to care for all beneficiaries, ensuring the long-

term sustainability and eectiveness of the program.

White Paper: Understanding Medicare Advantage Payment & Policy Recommendations 15

Briefly, BMA recommends the following:

• Maintain coding intensity adjustment at the statutory minimum level, to achieve stability

and adequacy of the prospective, capitated payment and enable plans and providers to

gather the data necessary for early intervention and care management;

• Improve risk model accuracy for individuals with multiple chronic conditions, considering

the cumulative impact of a large number of chronic conditions, the interaction between

behavioral/mental health conditions and physical health conditions, the dierences in

dual-eligible beneficiary costs given dierent eligibility pathways, and the potential for

using more than one year of data to establish risk scores;

22, 23

• Incorporate social determinants of health into the risk model as proposed and executed

by CMS and the National Quality Forum (NQF) for quality measures in the Star Rating

System. As Medicare Advantage grows and becomes increasingly complex, a better

understanding of how social determinants of health aect beneficiary costs, and

adjusting payments accordingly, will be critical;

• Validate the Encounter Data System to ensure accuracy of risk scores for Medicare

Advantage enrollees before progressing further in calculating risk scores using encounter

data; and

• Improve transparency of the risk adjustment model change process by improving the

notice and comment process, publishing and responding to all comments received, and

conducting open door forums.

3. Improve the accuracy of the benchmark calculation

Challenge. In order to measure average FFS spending to calculate county-level benchmarks,

CMS uses data for all FFS beneficiaries in a county, including those who have both Part A

and Part B, those who have only Part A, and those who have only Part B. However, in order

to enroll in a Medicare Advantage plan, beneficiaries must enroll in both Part A and Part B.

MedPAC has found that a smaller share of FFS Medicare beneficiaries are enrolled in both

Part A and Part B over the past few years.

24

MedPAC has also found that per beneficiary

spending is higher for beneficiaries enrolled in both Part A and Part B than the combined

total of average spending for all beneficiaries enrolled in Part A and all beneficiaries

enrolled in Part B. Finally, in its analysis of risk scores, MedPAC found that the average risk

score of beneficiaries enrolled in both Part A and Part B is higher than average risk scores

for all enrollees in either Part A or Part B.

Policy Recommendation. BMA supports MedPAC’s recommendation that CMS should

calculate Medicare Advantage benchmarks using FFS Medicare spending only for

beneficiaries enrolled in both Part A and Part B in order to improve accuracy in the

benchmark calculation.

White Paper: Understanding Medicare Advantage Payment & Policy Recommendations 16

4. Reward high quality by eliminating the benchmark cap for plans with

4+ stars

Challenge. The Quality Star Rating System program plays a key role in keeping Medicare

Advantage eective and innovative by incentivizing improvements in quality. Medicare

Advantage enrollees benefit from both these quality improvements and from the

requirement that plans use rebates that result from bidding below the benchmark and

quality bonuses to reduce enrollee cost-sharing or increase benefits. Under current law,

county-level benchmarks (including quality adjustments) are capped at their pre-ACA

levels.

The benchmark cap prevents plans in certain counties from receiving the bonus payments

they earn and prevents beneficiaries from receiving the full benefits of enrolling in a high-

quality plan. In 2017, benchmarks in half of counties across the country were constrained

in some way by the benchmark cap, meaning plans with 4 or more stars received a

benchmark quality bonus less than the statutory 5% or receive no quality bonus at all.

25

In

2016, more than 2 million Medicare beneficiaries were enrolled in 4-star plans but denied

enhanced benefits, including reduced cost-sharing, because of the benchmark cap.

Policy Recommendation. CMS should lift the benchmark cap for high quality, 4-star and

higher Medicare Advantage plans to ensure that all Medicare Advantage beneficiaries

receive the full benefits of enrolling in a high-quality plan.

White Paper: Understanding Medicare Advantage Payment & Policy Recommendations 17

1

42 U.S.C. Sec. 1395w-23(b). Web.

2

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, “Monthly Contract and Enrollment Summary Report,” July 2017.

Web.

3

Congressional Budget Oce, “June 2017 Baseline,” June 29, 2017. Web.

4

Better Medicare Alliance, “Beneficiaries Continue to Choose Medicare Advantage,” October 2017. Web.

5

Kaiser Family Foundation, “Medicare Advantage 2018 Data Spotlight: First Look,” October 2017. Web.

6

Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, “Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy,” March 2018.

Web.

7

Better Medicare Alliance, “Beneficiaries Continue to Choose Medicare Advantage,” October 2017. Web.

8

Better Medicare Alliance analysis of CMS Medicare Advantage Enrollment Data, July 2018.

9

Ibid.

10

Ibid.

11

Ibid.

12

Ibid.

13

Paulette C. Morgan, “Medicare Advantage—Proposed Benchmark Update and Other Adjustments for

CY2018: In Brief,” Congressional Research Service, February 17, 2017. Web.

14

Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, “Medicare Advantage System Payment Basics,” October 2017.

Web.

15

Paulette C. Morgan, “Medicare Advantage—Proposed Benchmark Update and Other Adjustments for

CY2018: In Brief,” Congressional Research Service, February 17, 2017. Web.

16

Paulette C. Morgan, “Medicare Advantage—Proposed Benchmark Update and Other Adjustments for

CY2018: In Brief,” Congressional Research Service, February 17, 2017. Web.

17

For further information on risk adjustment, see Better Medicare Alliance, “Medicare Advantage Risk

Adjustment: Evolution and Current Issues,” October 2017. Web.

18

Better Medicare Alliance, “Medicare Advantage Risk Adjustment: Current Issues, Evolution & Policy

Recommendations,” March 2018. Web.

19

Milliman, “Regulatory Oversight in Medicare Advantage,” June 24, 2016. Web.

20

Better Medicare Alliance, “Medicare Advantage Risk Adjustment: Current Issues, Evolution & Policy

Recommendations,” March 2018. Web.

21

United States Government Accountability Oce, Medicare Advantage: Limited Progress Made to Validate

Encounter Data Used to Ensure Proper Payments, January 2017. Web.

22

United States Senate, Committee on Finance, Bipartisan Chronic Care Working Group, Policy Options

Document, December 2015. Web.

Sources

White Paper: Understanding Medicare Advantage Payment & Policy Recommendations 18

23

Better Medicare Alliance, “Medicare Advantage Risk Adjustment: Current Issues, Evolution & Policy

Recommendations,” March 2018. Web.

24

Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, “March 2017 Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy,

Chapter 13: Status report on the Medicare Advantage Program,” March 15, 2017. Web.

25

Paulette C. Morgan, “Medicare Advantage—Proposed Benchmark Update and Other Adjustments for

CY2018: In Brief,” Congressional Research Service, February 17, 2017. Web