STANFORD MEDICINE SEPTEMBER 2018

White Paper:

The Future of Electronic

Health Records

Introduction

Ten years ago, one doctor in 10 kept

digital records on their patients. The

other 90 percent made notes on paper

and stored them in manila folders on

shelves and in filing cabinets.

Paper records had some obvious

disadvantages. They took up space,

they were diicult to share with

other physicians, hospitals, and

insurance companies.

Patients switching doctors, hospitals,

or places of residence could not easily

bring their records with them.

In 2009, in the wake of the financial

crisis, the federal government acted

to remedy this situation. The Health

Information Technology for Economic

and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act set

aside $27 billion of federal funds

to encourage health care providers

to adopt electronic health record

(EHR) systems, and more money was

subsequently made available for training

and assistance. All told, the federal

government spent about $35 billion on

bringing the U.S. health care industry

into the electronic age. The program was

highly successful in that it made EHRs

commonplace. Today, nine in 10 doctors

have adopted them. “We have made a

colossal transformation in a relatively

short period of time,” says Lloyd Minor,

MD, Dean of Stanford Medicine. “But we

have not realized the potential benefits

of the data that exist in electronic health

records.”

Indeed, many of the benefits of EHRs

have been elusive. As implemented

today, EHRs have too many of the

drawbacks of paper records. The

promise of being able to send them

easily from one oice to the next has

been hampered by a lack of standards

and perverse incentives in the health

care marketplace to hoard information.

Worse, EHRs, with their cumbersome

user interfaces and onerous billing

requirements, have become a burden

to doctors and nurses, contributing

to burnout and information overload

among physicians, and degrading

patient care. “A clinician will make

roughly 4,000 keyboard clicks during a

busy 10-hour emergency-room shi,”

writes Abraham Verghese, Professor for

the Theory and Practice of Medicine at

Stanford Medicine, in the New York

Times Magazine.

“In the process, our daily progress

notes have become bloated cut-and-

paste monsters that are inaccurate

and hard to wade through.”

Although EHRs have many problems,

there are reasons to believe that

they will eventually start living up to

their promise. With some changes in

technology, regulations, and attention

to training, EHRs may soon serve

as the backbone of an information

revolution in health care, one that will

transform health care the way digital

Future of EHR

“

There are a lot

of reasons to be

optimistic that

we will be able to

have both high-

tech and high-

touch medicine.

-Lloyd B. Minor, MD

Carl and Elizabeth

Naumann Dean

Stanford University School

of Medicine

technologies are changing banking,

finance, transportation, navigation,

Internet search, retail, and other

industries. Regulations are being put in

place that will put patients in control of

their own health records and facilitate

the sharing of data among health care

organizations. Engineers are developing

artificial intelligence technology that can

“take notes” for physicians, summarize

the important points from a patient’s

record and assist in medical decision

making. Apple’s recent app for medical

information, which gives third-party

developers the ability to pull information

from health records, is expected to be

the first of many developments that

brings health care data to patients’

fingertips. In August, technology firms

including Alphabet, IBM, Amazon and

Apple pledged to “share the common

quest to unlock the potential in health

care data, to deliver better outcomes

technologies are changing banking,

finance, transportation, navigation,

Internet search, retail, and other

industries. Regulations are being put in

place that will put patients in control of

their own health records and facilitate

the sharing of data among health care

organizations. Engineers are developing

artificial intelligence technology that can

“take notes” for physicians, summarize

the important points from a patient’s

record, and assist in medical decision

making. Apple’s recent app for medical

information, which gives third-party

developers the ability to pull information

from health records, is expected to be

the first of many developments that

brings health care data to patients’

fingertips. “There are a lot of reasons

to be optimistic that we will be able to

have both high-tech and high-touch

medicine,” says Minor.

This white paper is intended to provide

a roadmap for this transformation. We

will explore the current state of the

EHR, reporting the results of a survey by

Stanford Medicine and The Harris Poll

“

A clinician will

make roughly

4,000 keyboard

clicks during a

busy 10-hour

emergency room

shi.

-Abraham Verghese, MD, MACP

Linda R. Meier and Joan F.

Lane Provostial Professor

Stanford University School

of Medicine

of physicians and their experiences and

attitudes with EHRs.

Most important, we will oer some

concrete suggestions for solving the

problems that physicians confront

today with regard to EHRs and how

the medical profession can fully

leverage the power of medical data

over the next decade.

We will distill the key ideas from a

symposium of health care industry

professionals, hosted by the Stanford

University School of Medicine on June

4, 2018, including a vision of how

EHRs could contribute positively to

health care and medicine by 2028,

how to exploit the best ideas from the

tech industry to make it happen, and

immediate and practical steps that

health care professionals can take

towards this vision.

Future of EHR

The Vision

for 2028

What would a health care

system with a fluid movement of

information and state-of-the-art

technology look like?

In an ideal world, physicians, nurses,

and other health care practitioners

would simply take care of their patients

without having to think much about

health records at all. They would devote

most of their time and attention to

interacting with the patient. Whatever

the outcome of the examination,

relevant information would flow

seamlessly to all parties necessary to

handle the patient’s progress through

the health care system—to insurance

companies, hospitals, other physicians,

and the patient.

In terms of the electronic health record

itself, this means that the EHR would be

populated with little or no eort. When

the nurse or doctor takes vital signs,

these would be automatically uploaded.

In the exam room, an automated

physician’s assistant would listen to the

interaction between doctor and patient,

and, based on the communication in

the room and verbal cues from the

clinicians, record all relevant information

in the physical exam.

The automated physician’s assistant

would also oer options for taking

action. It would use artificial intelligence

(AI) technology to synthesize medical

literature, the patient’s history, and

relevant histories of other patients

whose records would be available in

anonymized, aggregated form. When

the assistant hears a complaint from

the patient, the EHR would populate

dierent possible diagnoses for the

clinician to investigate. It would also

be sensitive to an individual patient’s

characteristics—lifestyle, medication

history, genetic makeup—and bring

all the relevant medical knowledge to

bear on what would be best treatment

options for a particular patient.

This kind of medical decision-making

support would bring Precision Health

into the doctor’s practice, with the

goal of keeping people healthy.

Knowledge would flow not only to the

clinician that is caring for a particular

patient, but also to public health oicials

interested in the population at large. We

can imagine a future where EHRs are

part of a rich, seamless data stream that

facilitates doctor-patient rapport even as

it delivers real-time diagnostic support.

Clinicians would be free to do what they

do best: use their brains and interact

with other human beings.

Future of EHR

The current reality of EHRs is less

inspiring. As a starting point, The Harris

Poll conducted a survey on behalf of

Stanford Medicine that explores the

attitudes physicians have about EHRs in

their practices. The online survey took

place between March 2 and March 27,

2018. Respondents were 521 primary

care physicians in the United States,

whose medical specialty was defined

as Family Practice, General Practice or

Internal Medicine, recruited through

the American Medical Association lists.

Results were weighted to bring gender,

region, and medical specialty into line

with actual proportions of doctors in

the country. They were licensed to

practice in the U.S. and had been using

their current EHR system for at least one

month.

When EHRs were first introduced, the

hope was that they would liberate

patient health information and

would lead to better insights and

care.

But primary care doctors are clear in

the survey and in conversation that

the opposite has happened: EHRs too

oen get in the way of better care. In the

Stanford Medicine-Harris poll, doctors

report that more than 60 percent of

their time spent on behalf of patients

is actually devoted to interacting with

EHRs. Half of oice-based primary care

physicians think using an EHR actually

detracts from their clinical eectiveness.

Writes Verghese:

“In America today, the patient in

the hospital bed is just the icon, a

placeholder for the real patient who

is not in the bed but in the computer.

That virtual entity gets all our

attention.”

Christine Sinsky, MD, Vice President of

the American Medical Association in

charge of professional satisfaction, says

that these results accurately reflect her

experience as a physician. “I’ve made

site visits to over 50 practices. I’ve given

more than 200 presentations at society

meetings, health system meetings,

grand rounds at academic medical

centers. The conversations I’ve had in

those places align with findings of the

Stanford Medicine survey,” she says. “If

anything, they underestimate the degree

of professional angst and moral distress

that physicians have experienced as

they deal with this tool.”

The angst comes when physicians have

to make trade-os between the amount

of time they spend with their patients,

the amount of time they spend creating

documentation of their encounter with

each patient, and the amount of time

they have le for families and friends.

“

If anything, they

underestimate

the degree of

professional angst

and moral distress

that physicians

have experienced

as they deal with

this tool.

-Christine Sinsky, MD

VP of Professional

Satisfaction

AMA

2018: The Current

State of Electronic

Health Care Records

Future of EHR

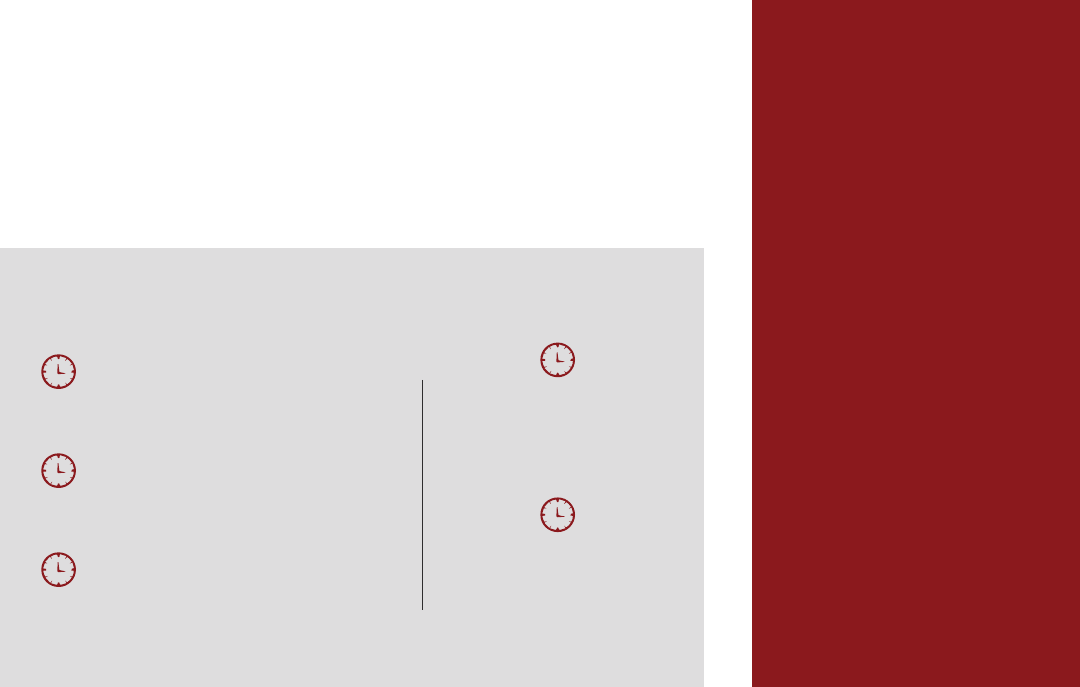

11.8 minutes

Interacting directly with a

patient during a visit

8.3 minutes

Interacting with the EHR

system during a patient visit

10.6 minutes

Interacting with the EHR

system outside of a patient visit

18.9

Total time

spent in EHR

62%

of time spent in the EHR

per patient

How Physicians Are Spending Their Time Per Patient

Source: Stanford Medicine-The Harris Poll

Physicians in their practice have to

synthesize a great deal of information,

and EHRs oen make this task more

diicult, says Sinsky. EHRs are oen

designed with dropdown menus that

increase the cognitive workload on the

physician. Doctors report anecdotally

being able to see fewer patients, having

to spend more time working, and feeling

dissatisfaction with the work they do.

Whereas previously a physician

might dictate a brief medical note,

they are now oen responsible

for the clerical work of formatting

electronic notes, which increases the

time spent on documentation.

Medicare and Medicaid reporting

requirements have made this problem

worse by requiring physicians to

document every action taken on behalf

of the patient. “As good as the EHRs

are as they exist right now, they’re not

nearly as intuitive as they should be,”

says Marc Harrison, MD, President and

CEO of Intermountain Healthcare.

“They actually can get in the way of the

patient-doctor interaction. As a nation,

we are taking our doctors and nurses

and making them into data-entry clerks.

It’s not fun, it contributes to burnout, it’s

non-value-added time.” Few physicians

see any clinical value in their EHRs. Only

8 percent cite factors related to clinical

matters, such as disease prevention

and management (3 percent), clinical

decision support (3 percent), and patient

engagement (2 percent). On the other

hand, 44 percent of physicians say the

primary value of EHRs is to serve as

digital storage.

Where do we go from here? Nearly

three-quarters of doctors in the poll

say the first order of business should

be improving the user interface of

EHRs to enhance eiciency and reduce

screen time. Half want to see data entry

shied to support sta and 38 percent

would welcome a highly accurate voice

recording technology that would act as a

scribe during patient visits.

The poll also indicated some

long-term concerns. More than 40

percent of doctors would like to see in

the next decade EHRs transformed into

a powerful tool that helps with clinical

“

They actually get

in the way of the

patient-doctor

interaction. We

are taking our

doctors and nurses

and making them

into data-entry

clerks. It’s not fun,

it contributes to

burnout, it’s non-

value-added time.

-Marc Harrison, MD

President and CEO

Intermountain Healthcare

Future of EHR

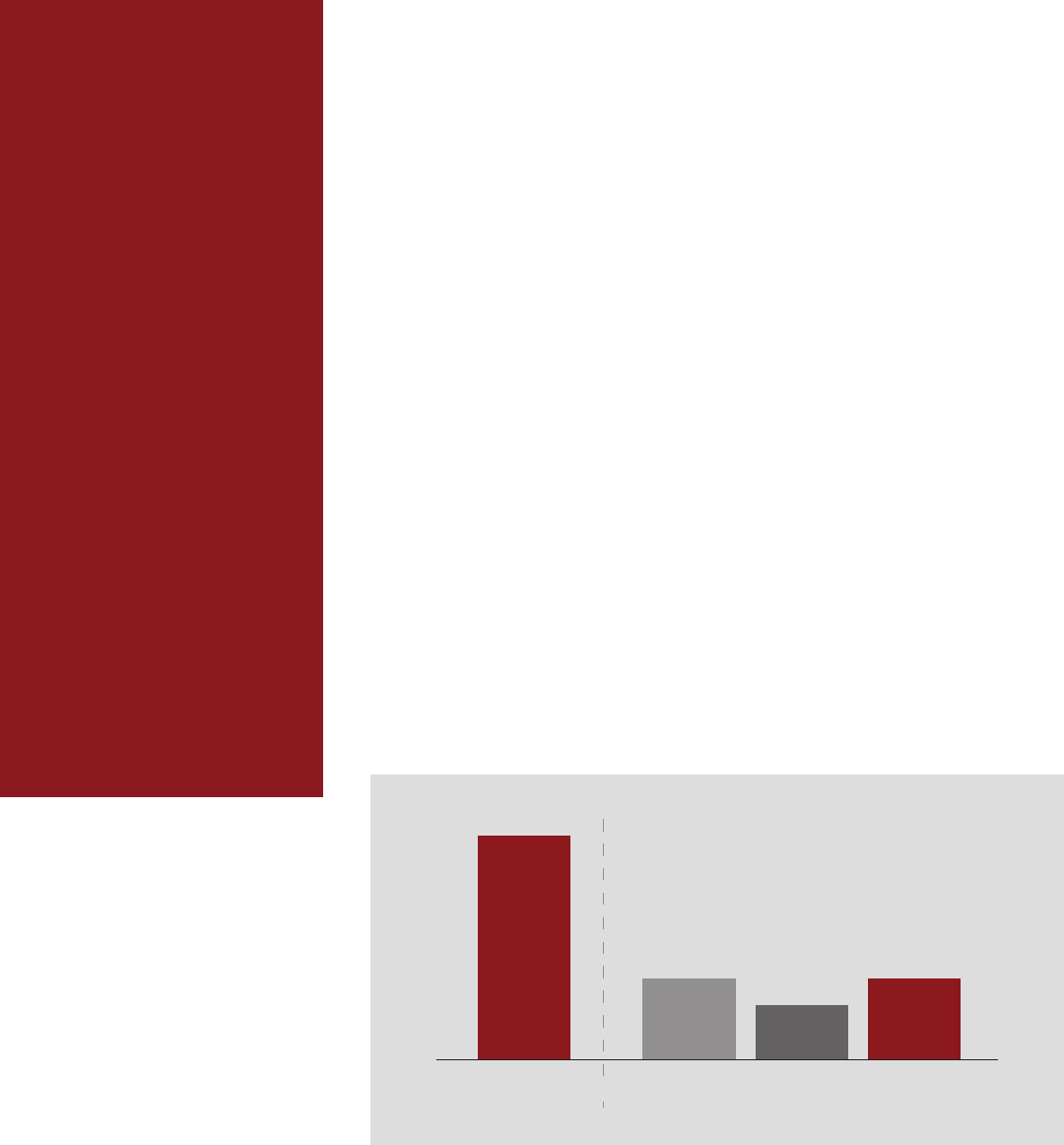

44 percent of physicians say the primary

value of the EHR is to serve as digital storage.

Only 8 percent cite factors related to

clinical matters.

TOTAL DISEASE

PREVENTION

CLINICAL

DECISION

SUPPORT

PATIENT

ENGAGEMENT

8%

3%

2%

3%

Source: Stanford Medicine-The Harris Poll

care, predictive analysis to support

disease diagnosis and prevention,

and population health management.

About a third would like to see financial

information integrated into the system

so that patients can weigh the costs of

their care options.

The top area of interest among

respondents was “interoperability”—the

need to make patient data available

easily and readily to professionals from

all parts of the health care system for the

benefit of the patient.

More than two-thirds of doctors

listed this as the No. 1 issue to fix

in the long term. To do that, we

have to have a radically dierent

health IT infrastructure—one that

promotes data sharing and is open to

developers.

The Importance of

Managing Change

Changes in technology, regulation,

and the business of health care

could transform medicine in the next

decade. In the short term, however,

physicians can take some steps to

alleviate the burden on their practices

from EHRs. Following best practices

for implementing EHRs can improve

physician satisfaction and improve

patient care. Judging from the

experience of some of the best-run

health care provider organizations,

the most practical and significant step

physicians can take is to better learn

how to use their current EHR systems.

The amount of training physicians get

in their EHRs has a big impact on their

own levels of satisfaction. Although

satisfaction is low on average among

physicians, surveys by KLAS, a health

care information-technology research

firm, show wide variation in satisfaction

levels among organizations, which

suggests that some are managing their

use of EHRs better than others. “While

less than half of physicians feel that their

EHR enables quality care, we’ve come

across a half dozen organizations where

over 75 percent of their physicians feel

that their EHR enables high-quality

care,” Taylor Davis, Executive Vice

President for Analysis and Strategy at

KLAS Enterprises, told the Stanford

Medicine symposium.

These organizations are not necessarily

the ones that have been most aggressive

at adopting the latest technology.

Instead, they emphasize teamwork

and training—and they’ve devoted

higher than average amounts of time to

training physicians to use EHRs. “Their

physicians realize that it’s a myth that

the EHR is going to be intuitive enough

to use out of the box,” said Davis. “It’s

not their technology, it’s their change

management.”

“

While less than

half of physicians

feel that their EHR

enables quality

care, we’ve come

across a half dozen

organizations

where over 75

percent of their

physicians feel that

their EHR enables

high-quality care.

-Taylor Davis

EVP, Analysis and Strategy

KLAS

Future of EHR

Short-Term EHR

Fixes

1 of 4 PCPs believe there should be

better training on how to

maximize the value of their EHR

27%

Source: Stanford Medicine-The Harris Poll

Some organizations are trying to limit

physician training for using EHRs to

an hour or two, while others put them

through two-week programs. “What’s

clear is that the organizations with the

least physician burnout are the ones

where physicians have had longer

training sessions,” says C.T. Lin, MD, Chief

Medical Oicer at University of Colorado

Health.

“And it’s not about how to use the

EHR. It’s about how we provide care,

with the EHR as one of the main

tools.”

A few years ago, Lin and his colleagues

at Colorado Health realized that many

of the physicians and nurses at its 400

clinics were dissatisfied with their EHRs.

They started an experiment, called

Sprint, in which they sent an 11-person

team to one clinic at a time to perform

custom training and development.

The goal of the Sprint team was to

address physician burnout and help

the clinic work better as a team. The

team was composed of one physician

informaticist, one nurse informaticist,

one project manager, four analysts who

can build things, and four trainers.

When the team would show up at a

clinic, physicians and administrators

would oen insist that they needed

nothing less than a complete overhaul

of the systems they use for keeping

electronic patient records. Oen,

however, their current systems already

provided much of the specific features

and functionality they needed.

“Typically, three-quarters of what they

ask for the system already does,” says

Lin. “We would say, ‘Oh, you know the 17

clicks you have to click to perform that

task? Try that button instead.’ And they

would say, ‘How long have we had one

of those?’”

The reason clinicians didn’t know

about features they needed is

because they didn’t get adequate

training at the outset, or they

weren’t brought up to speed when

new systems were rolled out or

incremental changes were made.

“

People get this

sort of empowered

feeling of like, now

that you’ve le,

we can carry on

the work because

you’ve shown us

a better way of

working. That’s the

surprising finding

out of Sprint.

-CT Lin, MD

Chief Medical Information

Oicer

UCHealth

Future of EHR

TRAINERS

ANALYSTS

PHYSICIAN

INFORMATICIST

PROJECT

MANAGER

NURSE

INFORMATICIST

Responsibilities

Sprint Teams

30%70%

Develop methods

for better

communication

Help build

things the record

systems can’t do

For this reason, each Sprint team comes

with four trainers who bring physicians

and other practitioners up to speed.

In many cases, management failed to

design the clinic’s workflow to take

advantage of the capabilities of the EHR.

About 30 percent of a Sprint team’s job

is to build things that the clinic’s current

records system doesn’t do. These can

include making up a flow sheet or a new

kind of synopsis report—anything that

a physician needs for their specialty but

for one reason or another never got. The

team generally delivers these projects

a day or two aer a physician asks for

them. “People feel like, at the end of

those two weeks, someone cares,” says

Lin.

The Sprint team also inculcates better

habits of communication among

members of clinical teams. For instance,

they introduce the practice of holding

team huddles every day. “People get this

sort of empowered feeling of like, now

that you’ve le, we can carry on the work

because you’ve shown us a better way of

working,” says Lin. “That’s the surprising

finding out of Sprint.”

Colorado Health assembled its first

Sprint team by borrowing from its

existing sta. Early on, executives

considered disbanding the team, but

its reputation had already spread to

department heads, who were eager

to know when they would be seeing a

Sprint team in their clinic. Two years

aer the experiment was started,

Colorado Health put together a second

team. The SWAT-team approach has

its drawbacks. It takes resources and

suers from a lack of scalability. Even

with two teams and a rapid-fire ethos, it

will take 10 years for Colorado Health’s

two teams to work through 400 clinics.

An alternative, says Lin, is to be strategic

about which pain points to target. If

an organization can’t aord to create a

SWAT team of 11 people for two-week

stints, it may be possible to construct

a team of, say, three people who can

accomplish half as much. “If the New

York Times publishes a béarnaise sauce

recipe that’s not in your fridge, you

have to work with what you’ve got,”

says Lin. “Can I get to 80 percent of

the deliciousness using what I already

have?”

Other health care organizations have

used up-front training to achieve

better physician satisfaction.

NorthShore University HealthSystem

created an onboarding program for

physicians that called for four to six

hours of training on their Epic EHR

systems. Within two weeks, physicians

also completed three full days of one-

on-one training by clinical trainers

with backgrounds primarily in nursing.

The amount of required training time

is adjusted if physicians can show

proficiency with an EHR and completed

their residency in an environment that

uses Epic. Training time can also be

extended as needed.

NorthShore’s clinical trainers typically

meet recently hired physicians at the

physician’s oice one hour prior to the

first scheduled patient. The trainers

get the physicians set up in the system

and answer questions. Trainers stay

the entire day to provide one-on-one

support. This process is repeated on

the second day. The trainer returns the

following week to ensure that there are

no remaining concerns about how to

use the EHR.

Greater Hudson Valley Health System,

a community hospital, got good results

by enlisting physicians to help them

prioritize development tasks. This

allowed them to reduce the time to

implement changes requested by

physicians to within two days. Greater

Hudson Valley also established a

governance process that gave the

organization some nimbleness in

responding to health crises, such as a

measles outbreak in 2018. This idea was

to allow for changes in workflows in

response to a crisis without introducing

confusion. Their solution was to have

analysts meet regularly with clinicians

to determine the top five issues

they want action on. The hospital’s

information technology sta also began

Future of EHR

to use Epic’s analytics tools to measure

productivity, to find the best workflow

that increases the quality of patient

care. During the measles outbreak,

IT met with the hospital’s lawyers,

quality-control personnel, nurses, and

infectious disease experts to determine

how best to modify EHRs to make them

more useful in managing the crisis.

The changes took a matter of hours to

implement.

Central to the success of Great Hudson

Valley’s program is making analytics

data available to physicians. Since the

clinicians helped narrow down the list

of priorities, it is important that they are

able to access data they need to make

appropriate decisions.

For physicians and health care

organizations that handle Medicare

and Medicaid patients, the federal

government is beginning to move

away from some of its more onerous

requirements for documenting the

patient-doctor interaction.

Its recent “Patients Over Paperwork”

initiative, announced in June 2018,

would consolidate some Medicare fee

structures for outpatient

visits, reduce clerical tasks associated

with coding and billing administration,

and allow doctors and other

practitioners to focus on documented

changes since the patient’s last visit

rather than re-documenting information.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid

Services (CMS) estimates that the new

regulations would save nearly 30,000

hours spent on billing administration.

If these changes are adopted, they

might relieve some of the burden on

physicians in the next few years.

Ineiciencies in Billing

and Reimbursement

Physicians and patients alike have their

favorite anecdotes about the problems

of the U.S. health care system. Many

of these stories center on the process

of billing and reimbursement. Terry

Gilliland, MD, Senior Vice President and

Chief Health Oicer at Blue Shield of

California, told the Stanford Medicine

symposium that overhead for billing

transactions accounts for 6 percent of

a payer’s costs. One practice reported

that it takes a trained registered nurse

45 minutes on average to get insurance

pre-authorization for a CT scan. Another

practice reported that, over the course

of dealing with all of their dierent

payers and care organizations, they are

required to fill out 200 dierent forms.

In general, health care billing in the U.S.

is characterized by a pervasive fear of

technology and ineiciency.

“This is an extremely fragmented

manual process that is not

benefitting many people,” says

Gilliland.

One problem is a lack of automation

of manual processes. About a third

of physician practices insist on doing

business with paper forms and fax

machines. A physician’s oice might fill

out a claims form on paper and fax it

to the payer, who would pay someone

to transcribe it into their system. Then

the payer will identify information that

is missing in the form but is needed

to process a claim. The form then gets

faxed back to the doctor’s oice, which

addends it and faxes it back. The payer

then has to pay someone to transcribe

the information into the system. These

kinds of ineiciencies drive up the cost

of transactions.

Future of EHR

Ineiciencies

In Billing and

Reimbursement

One practice reports it takes a

trained nurse 45 minutes, on

average, to get insurance

pre-authorization for a CT scan.

Another practice reports that,

over the course of dealing with all

of their dierent payers and care

organizations, they are required

to fill out 200 dierent forms.

Despite the rapid adoption of EHRs,

there has not been a commensurate

reduction in fragmentation and

automation in the realm of billing.

This is ironic considering that the

conventional wisdom among physicians

is that billing is the primary purpose

of EHRs in the first place. Standards

for Application Programming

Interfaces (APIs), which allow soware

from dierent devices to exchange

information securely and eiciently,

may help alleviate some ineiciencies

in billing. (We’ll discuss APIs further

below.) For instance, an API may give a

payer access directly to the information

it needs to process a claim, rather

than having to exchange faxes with

the doctor’s oice. The change in

recent years from transaction-oriented

reimbursement schemes, in which

health care providers are paid for,

and have to document, each act they

perform, to those that emphasize the

value of health care services to the

patient, has lowered the volume of

forms and documentation somewhat.

Fewer practices are required to

document things that they’ve done to

get reimbursement.

Physicians: Junk the fax machine.

Every doctor’s oice ought to

embrace electronic communications.

“For the 30 to 40 percent of American

practices that are unwilling to give

up the fax machine and are unwilling

to receive electronic payments,

perhaps there has to be a culture

shi,” Gilliland told symposium

attendees. Federal and private payers

may be able to help in this regard by

providing incentives. Even simple

changes such as physician practices

shiing to a payer’s portal website,

rather than insisting on using faxes

and paper payments, would create

significant eiciencies.

Physicians must start accepting

electronic payments. Many doctors’

oices are reluctant to allow payers

to transfer funds electronically for

fear that they would also be able to

make withdrawals.

Payers need to support physician

practices. Providing in-kind support

to providers in exchange for sharing

clinical and claims information would

help practices adopt technology.

For instance, payers could provide a

dashboard back to providers so that

they can get analytical insights about

their utilization and costs. This would

have the added benefit of helping

them make the transition to value-

based billing.

Create common standards across

payers. If health care insurers and

other payers agree on a common

set of data and formats, they would

greatly reduce the bureaucratic

burden on small practices who now

must fill out so many dierent forms.

Streamline pre-authorization.

Decreasing the hassle and time to

process claim pre-authorizations

would reduce ineiciencies and

2.

3.

Future of EHR

4.

Gilliland identified some

practical, short-term steps

to help streamline billing:

1.

5.

enhance patient care. Physician oices

should get instant feedback on pre-

authorizations. It should not take 45

minutes of a nurse’s time on the phone

to get authorization.

Artificial Intelligence

Can Improve the Doctor-

Patient Interaction

Artificial intelligence holds great promise

for alleviating some of the burden on

physicians of working with electronic

health records and freeing the physician

to focus on the patient during an

examination rather than on filling

out forms.

AI can potentially help physicians

get up to speed on a patient’s clinical

history, take notes and document the

visit with the patient, and support

medical decisions about what to do

next.

A clinician, upon walking into an

examination room, needs knowledge

about the patient’s background

and history. The EHR as currently

implemented in many organizations

is not designed to impart knowledge.

It contains a great deal of information,

but it can be diicult for physicians to

locate specific information needed for

informed decision-making. The quality

of much of the information is poor—

much of it is put there for non-clinical

purposes, such as documenting patient-

doctor interactions with billing codes to

satisfy regulators and insurers. “If you

could document just what you need

to take care of the patient, the volume

of notes in an EHR would shrink by 70

percent,” says Paul Tang, Vice President

and Chief Health Transformation Oicer

at IBM and a symposium participant.

All that extra information obscures

whatever useful information the EHR

contains, and makes the doctor’s job

harder.

Reading a patient’s record in the EHR

and gleaning insight from it is a high-

level cognitive task. “You wouldn’t ask

a medical student to do it or you’d get

back a ton of stu,” says Tang. He and

others are working on natural language

processing technologies that can read

“

If you could

document just

what you need to

take care of the

patient, the volume

of notes in an EHR

would shrink by 70

percent.

-Paul Tang, MD, MS

Chief Health Transformation

Oicer

IBM Watson Health

Future of EHR

Top Value Propositions

of Funded AI/ML Digital

Health Companies

(Total Funding Raised)

CLINICAL

WORKFLOW

HEALTH

BENEFITS

ADMIN

$514.8M

$469.5M

the text and data on the record and use

machine learning algorithms to choose

what information is relevant. The act

of writing a note is also a high-level

cognitive task: it requires a synthesis of

the clinician’s experience in the exam

room, which includes not only the

words that are spoken in conversation

but also non-verbal cues and medical

judgements in the physician’s head.

Clinicians used to write succinct notes

on paper records. Now they too oen

use the copy-and-paste function on their

computers to add excessive amounts of

information, which makes it that much

harder to find what’s relevant.

Source: Rock Health

Studies show that physicians who use

medical assistants to act as “digital

scribes” and record the content of the

patient-doctor interaction show far more

satisfaction and lower rates of burnout.

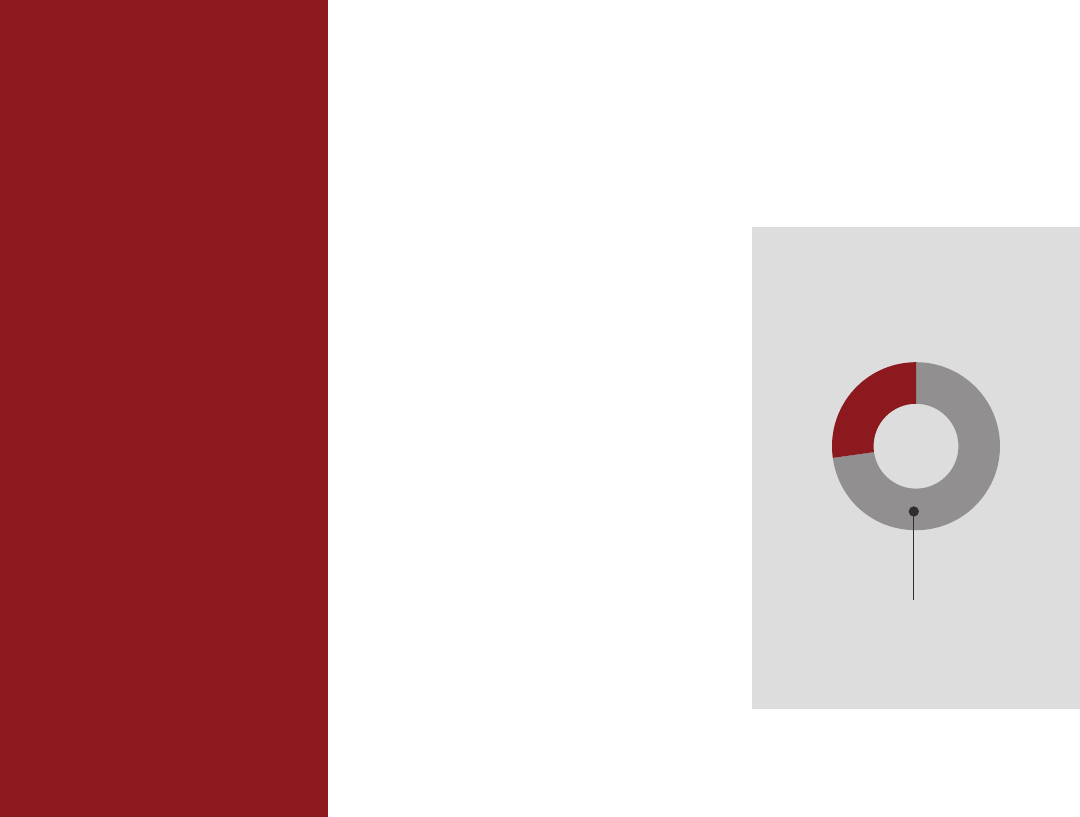

University of Colorado Health

experimented with increasing the ratio

of Medical Assistants (MAs) to physicians,

from 0.4 MAs per physician to nearly two.

Before the physician enters the room, an

MA spends 20 minutes talking with the

patient, updating the medical records

and handling minor medical issues,

such as vaccines and screenings. When

the physician walks in, the MA stays in

the room, acting as a scribe during the

exam. They found that over the course

of a year, this approach went a long

way to relieving physician burnout: the

metric they use to measure physician

burnout declined from 55 percent to 14

percent. Assigning two people for each

physician to act as scribe may not be a

cost-eective solution, however.

AI researchers are working on

automating the job of scribe. Google

and Stanford Medicine have been

working for more than a year on

a digital scribe project that would

listen to the dialogue in a patient

visit and take notes.

The idea is not merely to take a

transcription, but rather to knit the

dialogue into a narrative. In the study,

each doctor wears a microphone to

capture conversations with patients,

which are used to train machine-

learning algorithms in getting the gist of

a doctor-patient interaction. The goal is

to train the algorithm to generate a pithy

progress note.

Google researchers say that

its scribe can capture complex

conversations typical of a patient-

doctor conference even when family

members and other practitioners are

present in a noisy environment.

AI can also potentially assist doctors

in making medical decisions at the

end of a patient visit. For instance, if a

patient who is already on medication for

hypertension comes into the doctor’s

oice with high blood pressure, what

should the doctor do: increase the

dosage or try another drug altogether,

and if so, which one? Doctors oen have

to make these kinds of decisions with

incomplete information on the patient

or on population studies of the drug’s

eicacy. The physician then needs to

do considerable research to determine

the best medical course of action. An

AI assistant that could take in relevant

information about the patient in the

EHR and combine it with a review of the

medical literature could save the doctor

a great deal of time.

In a study recently published in Nature

Digital Medicine, researchers at the

University of California, San Francisco,

University of Chicago Medicine, Stanford

Medicine, and Google used an advanced

algorithm to predict unexpected

readmissions, long hospital stays, and

in-hospital deaths among 216,000 adult

patients using data from their EHRs. The

study suggests that machine-learning

algorithms can make sense of messy

electronic health record data, including

unstructured clinical notes, errors in

labels, and large numbers of input

variables, to make predictions about

patient health. Another study at Stanford

Medicine uses algorithms to si through

large databases, including electronic

health records, to detect patients who

likely have a certain genetic condition

that can lead to a fatal heart attack at a

premature age.

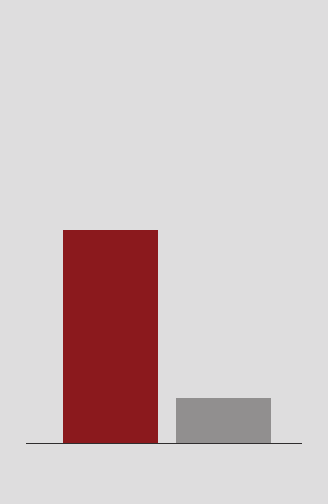

A combination of AI and information

CHART

55%

14%

Over the course of one year there was a

decrease in physician burnout at the

University of Colorado Health due to the

addition of more medical assistants to help

physicians with note entry.

Future of EHR

Physician Burnout

OVER ONE YEAR

BEFORE

AFTER

from patient records could also advance

the ball on Precision Health.

Based on an individual’s

characteristics, AI could draw

on sources of big data to

oer personalized treatment

recommendations, based on:

The patient’s past medical history

Genomic information

The way the patient metabolizes

certain drugs

Relevant medical literature

Similar patients in the population

Environmental and social factors

Intermountain Healthcare, for instance,

is studying the clinical and economic

implications of using genomics in the

treatment of behavioral health. It is

currently using genomics in the care of

people with depression—specifically

to determine which antidepressants at

which doses will be most eective for a

patient based on their particular drug

metabolism. The company is planning

similar studies for anti-psychotic and

bipolar patients. Combining genomics

with machine learning could be a

powerful predictive tool.

An AI-based decision support system

for individual doctors could serve as

a window to data from many other

sources, and could be a major tool in

preventive and personalized health.

An App-Based Ecosystem

Can Put Patients at the

Center

Perhaps the biggest disappointment

of EHRs is that they are still to a large

degree static. Although they store data

electronically, that data is still trapped

within the institutions that gather it.

The next step in the digitization of

health care, symposium participants

agreed, is to free up this information

in ways that enhance patient health

while protecting privacy. The goal is to

leverage data in the EHR to enhance

patient care. This should happen in an

information marketplace that empowers

patients and health care providers to

configure their own EHR experiences

and workflows.

Harris Poll respondents overwhelmingly

called for greater interoperability of data

in EHRs. In other words, the information

in EHRs should pass seamlessly

among health care organizations and

patients. This includes all the ways

patient records are currently exchanged

among providers and payers and

patients, but also new ways that would

enhance patient care. For instance,

aggregate data from EHRs would help

in determining what medical resources

should be deployed strategically across

a population to help manage risks.

“When predictive models are enriched

by clinical data, they are richer and more

accurate,” says Rishi Sikka, MD, President

of System Enterprises, Sutter Health.

If physicians can make more accurate

predictions, they can intervene in

meaningful ways to prevent illness.

Free movement of data would also

improve patient health by eliminating

unnecessary tests. Whenever a blood

test is done because the records of

a previous test were unavailable, or

“

When predictive

models are enriched

by clinical data, they

are richer and more

accurate.

-Rishi Sikka, MD

President, System Enterprises

Sutter Health

Future of EHR

whenever an x-ray is taken because

a previous image was not readily

available, patients are exposed to undue

risk.

A lack of available information also

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

makes it more diicult to make good

medical decisions. Physicians are oen

in the dark about what their patients do

aer they leave the examination room.

A doctor may not know, for instance,

whether a patient with diabetes has

filled a prescription for insulin, even

though this information is critical to the

patient’s health. “Typically, information

does not go back from pharmacy to

doctor,” says Roy Beveridge, Chief

Medical Oicer of Humana. “There’s no

feedback loop. This is simple to do if

there’s connectivity,” says Beveridge. “It’s

why interoperability is so important.”

Even organizations that have a greater

than usual need to exchange

information struggle with

interoperability. A survey published

in July 2018 in JAMIA of 68 hospitals

found that even those organizations

that frequently shared patients didn’t

do very well at exchanging records. Of

63 pairs of hospitals studied, 23 percent

reported worse information sharing

between the hospitals with which they

regularly share patients, with 17 percent

reporting better sharing and 48 percent

indicating no dierence. “New policy

eorts, particularly those emerging from

the 21st Century Cures Act, need to

explicitly pursue strategies that ensure

that [highest shared patient] providers

engage in exchange with each other,”

conclude authors Julia Adler-Milstein of

University of California, San Francisco,

who spoke at the Stanford Medicine

symposium, and Jordan Everson of

Vanderbilt.

One obstacle to the free flow of

information is perverse incentives in

the businesses that deal with EHR

systems. Health care organizations

that gather data about patients have

a proprietary interest in that data—

they want it to flow only if they are

compensated for it. “Unless there’s a

free exchange of data, your hospital

believes that its data is valuable to

them, and they’re not releasing it to the

“

This is simple

to do if there’s

connectivity,

it’s why

interoperability

is so important.

-Roy Beveridge, MD

Chief Medical Oicer

Humana

Future of EHR

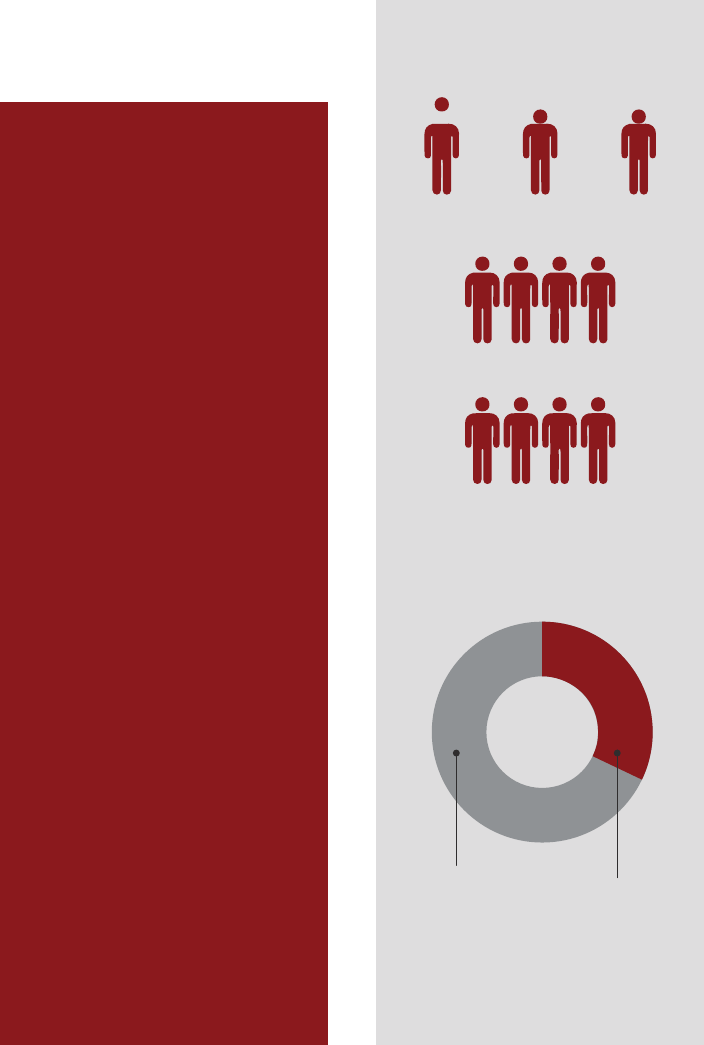

Reported worse

information sharing

Reported better

information sharing

Reported no dierence in

the information sharing

23% 17% 48%

Out of 63 Pairs of Hospitals Studied That

Regularly Share Patients

Source: Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association

ophthalmologist or the pharmacy,” says

Beveridge.

“If no one is sharing information,

this simple feedback loop doesn’t

occur, because everyone’s trying to

maximize their little bit of money.”

Congress acted in 2016, with the passage

of the 21st Century Cures Act, to fix the

lack of interoperability by authorizing

HHS to investigate cases in which patient

information is not shared and imposing

penalties. “It didn’t escape Congress

that some of this information wasn’t

being shared for a variety of reasons and

that people didn’t have health care on

their smartphones,” says Don Rucker,

MD, the National Coordinator for Health

Information Technology at the Oice of

the National Coordinator for Health IT,

part of the U.S. Department of Health

and Human Services (HHS). Rucker’s

oice is currently working to promulgate

rules that flesh out the provisions of

the Act by defining permissible types of

information blocking—instances when a

business can legally refrain from sharing

information—and establishing rules for

open APIs. “We believe those rules will

be powerful,” says Rucker.

Another obstacle is concern over privacy.

Currently the practice of handling

patient medical records is governed

by a combination of state rules and

the Health Insurance Portability and

Accountability Act of 1996, or HIPAA.

Devised in the early days of the AIDS

crisis to ensure the privacy of medical

diagnoses, HIPAA forbids dissemination

of patient data without the permission

of the patient except under specific

exceptions, such as some circumstances

in which health care providers need

to exchange data about patients they

have in common. Since some state laws

are more restrictive, some people are

hesitant to exchange data even when

they are allowed to.

Health care organizations tend to have

an overly-restrictive interpretation of

HIPAA rules, says Lucia Savage, Chief

Privacy and Regulatory Oicer at Omada

Health and a former Chief Privacy Oicer

at the Oice of the National Coordinator

“

Future of EHR

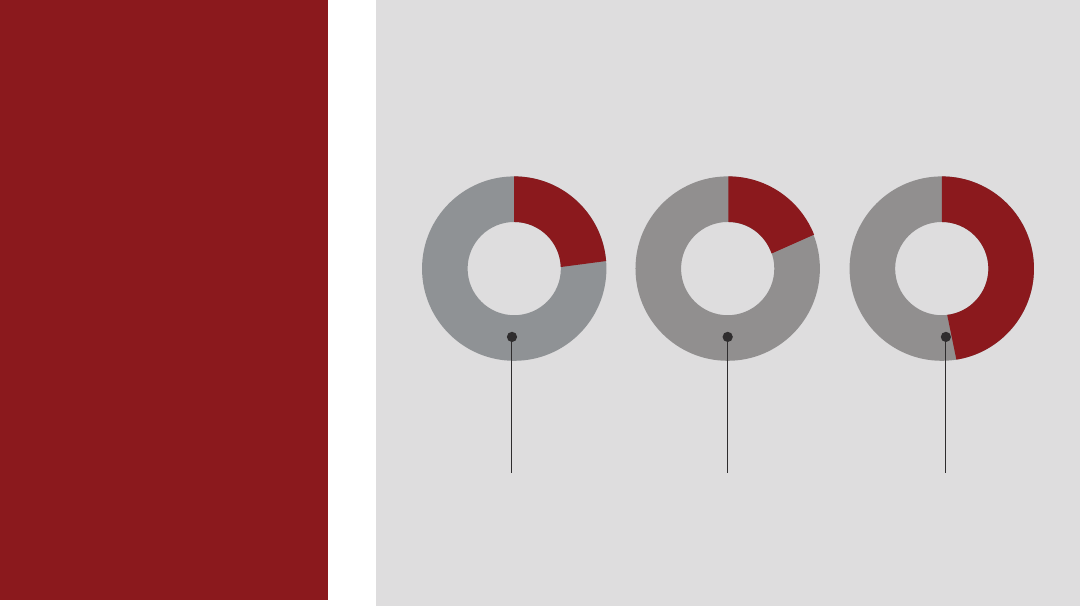

Long-Term EHR

Developments Physicians Want

Integrating financial information

into the EHR to help patients

understand the costs of their

care options

32%

Solving interoperability

(system-wide information

sharing) deficiencies

through various strategies

67%

Improving predictive analytics

to support disease diagnosis,

prevention, and population

health management

43%

It didn’t escape

Congress that

some of this

information wasn’t

being shared for a

variety of reasons

and that people

didn’t have health

care on their

smartphones.”

- Don Rucker, MD

The National Coordinator

for Health Information

Technology

ONC

Source: Stanford Medicine-The Harris Poll

of the more than 4,000 or so hospitals in

the U.S. The hope is that this situation

will improve once patients demand that

their health data is readily available, and

more institutions join the trend.

Demand from the patient user is

crucial to overcoming many of the

barriers that now stand in the way of

interoperability.

The foundation of an app-based health

care world would be the EHR. It would

be the basic repository of data about the

patient, and the patient would control

that data by granting permissions,

for Health Information Technology, in

HHS. Patients and executives are skittish

about privacy in the wake of revelations

about NSA surveillance and Facebook’s

sale of user data. An overly-restrictive

view of patient privacy when it comes to

medical records has hampered eorts to

make the data available in useful ways.

Participants at the Stanford Medicine

symposium were overwhelmingly of

the opinion that the risk of not sharing

data outweigh the risks to privacy. Says

Savage: “The best way to secure a health

record is to print it out on paper, stick it

in a box, and cover it with cement. But

then it’s of no use at all.”

A lack of standards for EHRs has also

held back progress in making data

freely available. EHRs oen contain a

mixture of formatted data and free text,

and standards vary widely from one

IT provider to the next. And they are

not interoperable with one another—

sometimes even within the same health

care organization.

In an eort to free up medical data, the

non-profit group Health Level Seven

International draed a standard called

FHIR, for Fast Healthcare Interoperability

Resources, that specifies how health

care apps can share data. HHS gave EHR

developers until January 2017 to create

FHIR-based open-specification APIs.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid

Services, a part of HHS, gave health

care organizations until January 2019

to provide data when a patient requests

it via a FHIR-based app. This means, in

eect, that data must be delivered when

a patient’s app requests it, so long as the

app is authentic and secure.

A year and a half later, the app

revolution hasn’t yet arrived. Resistance

from the medical community to new

technology is one factor. Privacy

concerns are another.

“People were worried that the app

would be a fraudulent app or that

identity credentials presented by the

app would be stolen,” says Savage.

“Tons of work has been done with

the medical professional to try to get

them used to this idea that in fact it’s a

completely legitimate exercise, legally

and technologically, for an individual

to give their credentials to an app that’s

acting on their behalf then for the app to

do the work of fetching.”

Many health care technology experts

believe that app-based medicine will

eventually break the logjam that is

keeping medical data from flowing

freely. Apple’s recent upgrade to its

Health app allows users to download

information from participating health

care providers onto their iPhones. At

the moment, only three or four dozen

institutions participate—a small fraction

“

Future of EHR

The best way to

secure a health

record is to print

it out on paper,

stick it in a box,

and cover it with

cement. But then

it’s of no use at all.

- Lucia Savage

Chief Privacy and Regulatory

Oicer

Omada Health, Inc.

through their acceptance of the terms

and conditions of the app, in accordance

with HIPAA and other regulations.

In a way, the EHR itself is a collection

of health care components, oen

integrated via APIs that standardize

how each one communicates with the

others. Thus, in the anticipated app-

based economy, those APIs would be

extended, using industry-accepted

security protocols, to encompass

information that patients, physicians,

and care teams could repurpose in

ways that are meaningful and useful.

It would also go a long way to solving

the interoperability problem, provided

those protocols are openly and easily

available, as is required in the Cures

Act. The power of an open API is that

it can be used to fetch information

without having to have nurses calling

insurance companies and assistants

sending faxes. The app itself contains

all the permissions and contractual

agreements required to carry out a

transaction, so there’s no checking

or double-checking involved. “It’s the

dierence between a dumb pipe and a

smart pipe,” says Aneesh Chopra, who

served as Chief Technology Oicer in

the Obama White House. “An API is a

smart pipe. It’s designed with all the

agreements built into it. It gives an app

developer the ability to get data quickly

in accordance with certain rules.” And

the app/API interaction leaves an audit

trail.

Patients, doctors, and health care

industry professionals could glean

insight from an ecosystem of health care

apps that interprets data, combines

data from dierent sources, and

communicates it to relevant parties—

patients, doctors, and health care

industry professionals. Patients could

use their smartphones to assemble their

own ecosystem of apps that meet their

own needs for health information, the

same way they’d use apps for checking

accounts or to apply for a mortgage or to

call an Uber.

The Veterans Health Administration is

trying to build such an ecosystem for its

9 million veterans and families. The VA,

which provides care at 1,240 facilities

globally, has made interoperability

a priority in its $10 billion plans

to modernize its EHR system. It is

partnering with vendors and other

health systems to ensure that its EHR

system will be 100-percent interoperable

across vendor EHRs and would

leverage APIs to create a developer-

friendly environment to nurture app

development.

About a dozen groups have signed

an industry pledge to support this

eort.

If each patient had a universe of health

care apps to pick and choose from, it

would help to democratize medical data,

Future of EHR

the way ATMs democratized banking.

From an information technology

standpoint, the challenge to medicine is

greater than it was for banking. Health

care data is inherently more complicated

than account balances and mortgage

payments. Medicine has had barely a

decade to wrestle with this particular

information challenge. The next decade

promises to be an eventful one.

For Medical Practices:

Invest in adequate EHR training when

onboarding physicians and bring

them up to speed when incremental

changes are made;

Enlist physicians to help prioritize

EHR development tasks and to

design clinical workflows that take

advantage of EHR capabilities (e.g.,

the Sprint team model);

Tailor the size and makeup of

physician development teams, taking

into account the clinical resources

available;

Deliver EHR development projects

soon aer physicians ask for them;

Establish an EHR governance process

that gives the clinical organization

nimbleness in responding to health

emergencies and crisis scenarios;

Make analytics data available to

physicians—presented in a way that

is intuitive at the point of care;

Shi non-essential EHR data entry

to ancillary sta. In the near term,

consider increasing the number of

medical assistants to act as “digital

scribes” (though this option is

expensive). In the long term, seek

automated solutions to eliminate

manual EHR documentation;

Re-evaluate your organization’s

interpretation of privacy rules;

Create opportunities for patients

to digitally maintain their records

(providing family history, medical

history, medications, health

monitoring data, etc.);

Junk the fax machine (if you still

have one) and embrace electronic

communications;

Start accepting electronic payments,

if you don’t already.

For Payers:

EHRs are a reflection of the current

fee-for-service payment paradigm.

Commit to value-based care

and provide adequate support

to physicians under this model,

including greater reimbursement for

preventive care services and the use

of digital health to engage patients;

Create common standards for billing

and quality reporting across payers;

Streamline pre-authorization

procedures;

Make claims data more accessible to

physicians to enable a longitudinal

view of their patients.

For Regulators:

Airm commitment to value-based

care and moving away from requiring

literal documentation of patient-

doctor interactions;

Create more flexibility around who

needs to enter data into the EHR,

as many tasks do not require the

expertise of a highly trained clinician;

Clarify information-blocking rules to

encourage open APIs and eliminate

perverse incentives to hoard

information.

A Summary

of Action Points

Future of EHR

For Technologists:

Clarify definitions of interoperability—

in collaboration with other

stakeholder groups—and adopt

common technical standards to

support them;

Develop systems and product

updates in partnership with your

end users—less than half of U.S.

physicians believe EHR developers

are responsive to their feedback;

Embrace open APIs and nurture a

community of developers to enable

an app-based ecosystem that puts

the patient in control;

Develop and market an ecosystem of

third-party apps that put patients in

control of their own health data;

Focus on eliminating the manual

entry of data into the EHR by

recruiting AI, natural language

processing, and other emerging

technologies;

Develop AI to increase the intelligence

of clinical information systems,

enabling them to:

Synthesize relevant information

in the EHR before each patient

encounter and present the

physician with a pithy summary;

Combine patient complaint

information with EHR databases

and the latest medical literature to

support medical decision making;

Deliver current and contextualized

information to each member of

a patient care team (i.e., enable

intelligent “care traic control”).

1.

2.

3.

Future of EHR

CHANGE OR ADAPT IN RESPONSE

TO USER FEEDBACK

Importance of vs. Satisfaction

with EHR Abilities

91%

Importance

44%

Satisfied

Source: Stanford Medicine-The Harris Poll

I

med.stanford.edu/ehr/whitepaper