Disabled Facilities

Grant (DFG) and

Other Adaptations

– External Review

Dec

2018

Main Report

Sheila Mackintosh, Paul Smith, Helen Garrett, Maggie Davidson, Gareth Morgan, and Rachel Russell

Disabled Facilities Grant (DFG) and Other Adaptations: Main Report

Acknowledgements

From the beginning we realised this was a rare opportunity to refresh and revitalise a

programme that helps thousands of people every year but has become overly

complicated through a changing health and care environment and nearly 30 years of

custom and practice. With only three months to complete the field work we are very

appreciative of all the contributions received.

Thank you to everyone who contributed to this review. Around 200 people came to the

initial free consultation workshops to consider, debate and vote on a range of options

that set the direction and tone of the narrative, supported by Foundations’ commercial

partners. Hundreds more watched the online videos and gave detailed feedback on

the options. A number of organisations also submitted more detailed written responses

that helped to further shape our recommendations. The passion and dedication with

which people expressed their views was remarkable.

We also spoke to a range of experts from within the sector and beyond whose

knowledge and varying perspectives either challenged our preconceptions or

reinforced our thinking – but in either case strengthened our recommendations.

Particular thanks also go to the members of the DFG Champions Facebook group who

provided instant opinions, case studies and data when we needed it.

A number of home improvement agencies and local authorities had previously

participated in ‘Rethinking DFG’ workshops with Foundations and the Social Change

Agency that strongly influenced our thinking on assessment and the upper limit.

We would like to acknowledge the support of both the Department of Health and Social

Care and the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government in developing

this review.

Finally, we would like to thank all our colleagues who provided support and

encouragement while we were busy writing up the findings. We would also like to thank

Anna Bornioli of the Centre for Public Health and Wellbeing who did the final edit of

the report.

We set out to #fixtheDFG and make it fit for purpose for the next 30 years and beyond.

We think our recommendations will go a long way to achieving that aim.

First published December 2018

University of the West of England

Centre for Public Health and Wellbeing

Faculty of Health and Applied Sciences

Frenchay Campus, Coldharbour Lane

Bristol BS16 1QY

ISBN 9781860435522

2

Disabled Facilities Grant (DFG) and Other Adaptations: Main Report

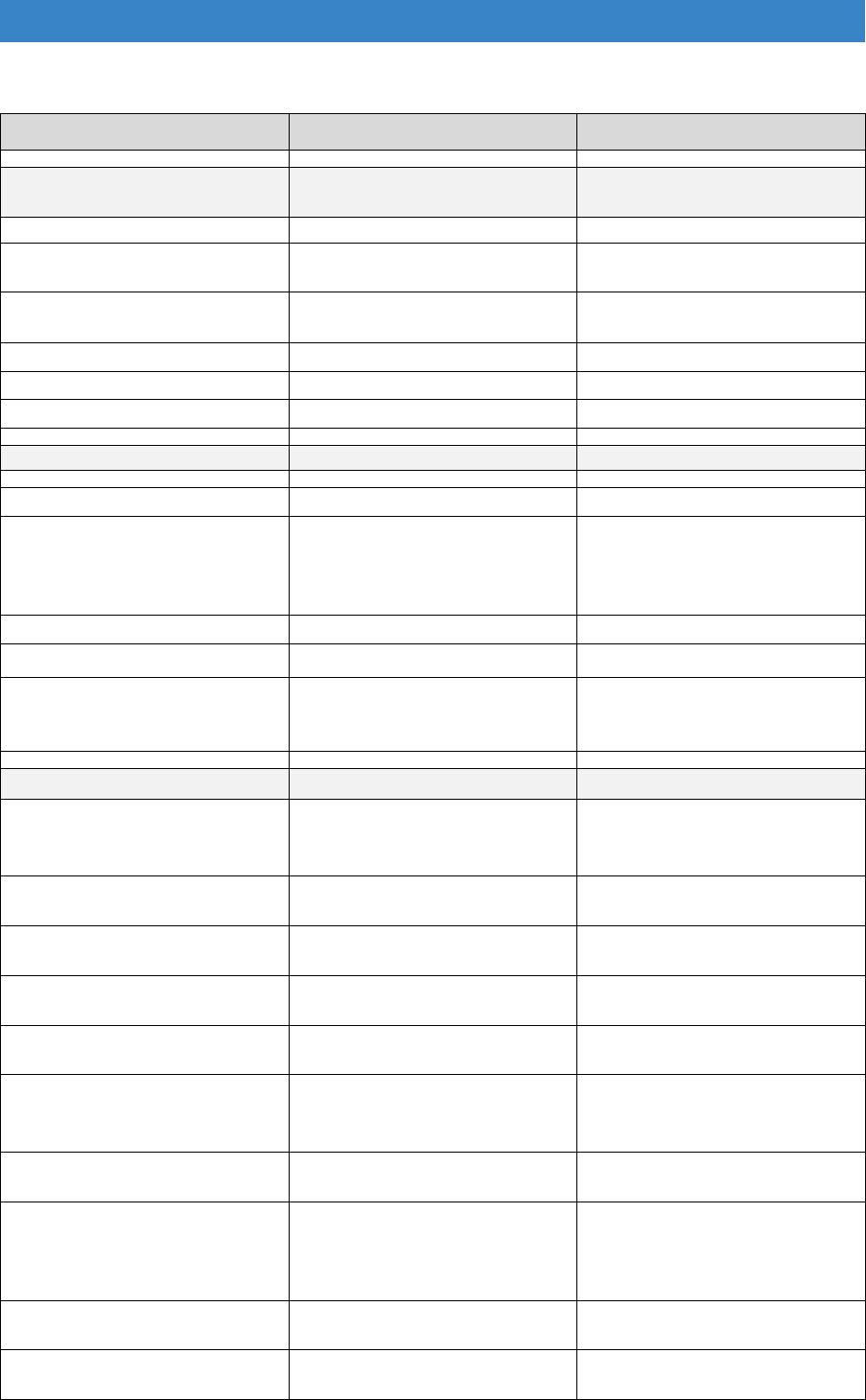

Contents

Acknowledgements.................................................................................................. 2

Glossary.................................................................................................................. 10

Chapter 1. Introduction.......................................................................................... 11

The aims of this review ......................................................................................... 11

Why the review is needed..................................................................................... 12

Changes since the last review .......................................................................... 12

Changing context.................................................................................................. 13

Integration ......................................................................................................... 13

Increased resources.......................................................................................... 14

Ageing population and rising numbers of disabled people ................................ 14

Changing expectations and impact of technology ............................................. 14

Changes in tenure............................................................................................. 14

Problems with service delivery ............................................................................. 15

The focus of the report.......................................................................................... 15

Chapter 2. Methodology ........................................................................................ 17

The review ............................................................................................................ 17

Methodology ......................................................................................................... 17

Part A How the DFG is used currently................................................................. 20

Chapter 3. DFG funding ......................................................................................... 21

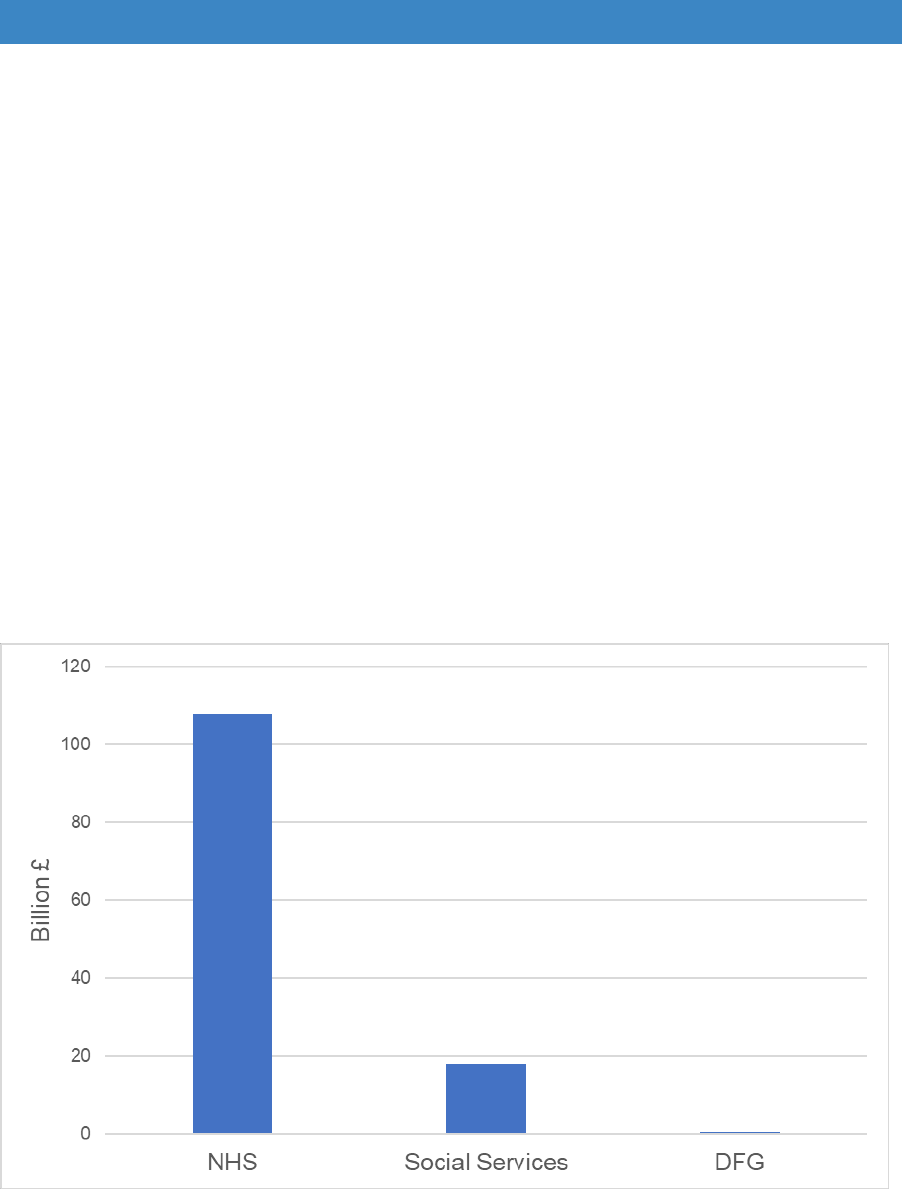

Funding sources and trends ................................................................................. 21

Reasons behind the trends................................................................................... 23

The need to increase the number of grants .......................................................... 26

Summary - funding issues .................................................................................... 26

Chapter 4. Who receives the grant ....................................................................... 27

Age of DFG recipients .......................................................................................... 27

Tenure of DFG recipients ..................................................................................... 29

Home owners.................................................................................................... 29

Registered providers ......................................................................................... 30

Private rented sector tenants ............................................................................ 31

Council stock..................................................................................................... 34

Rural housing ....................................................................................................... 34

Who is excluded from the DFG?........................................................................... 35

3

Disabled Facilities Grant (DFG) and Other Adaptations: Main Report

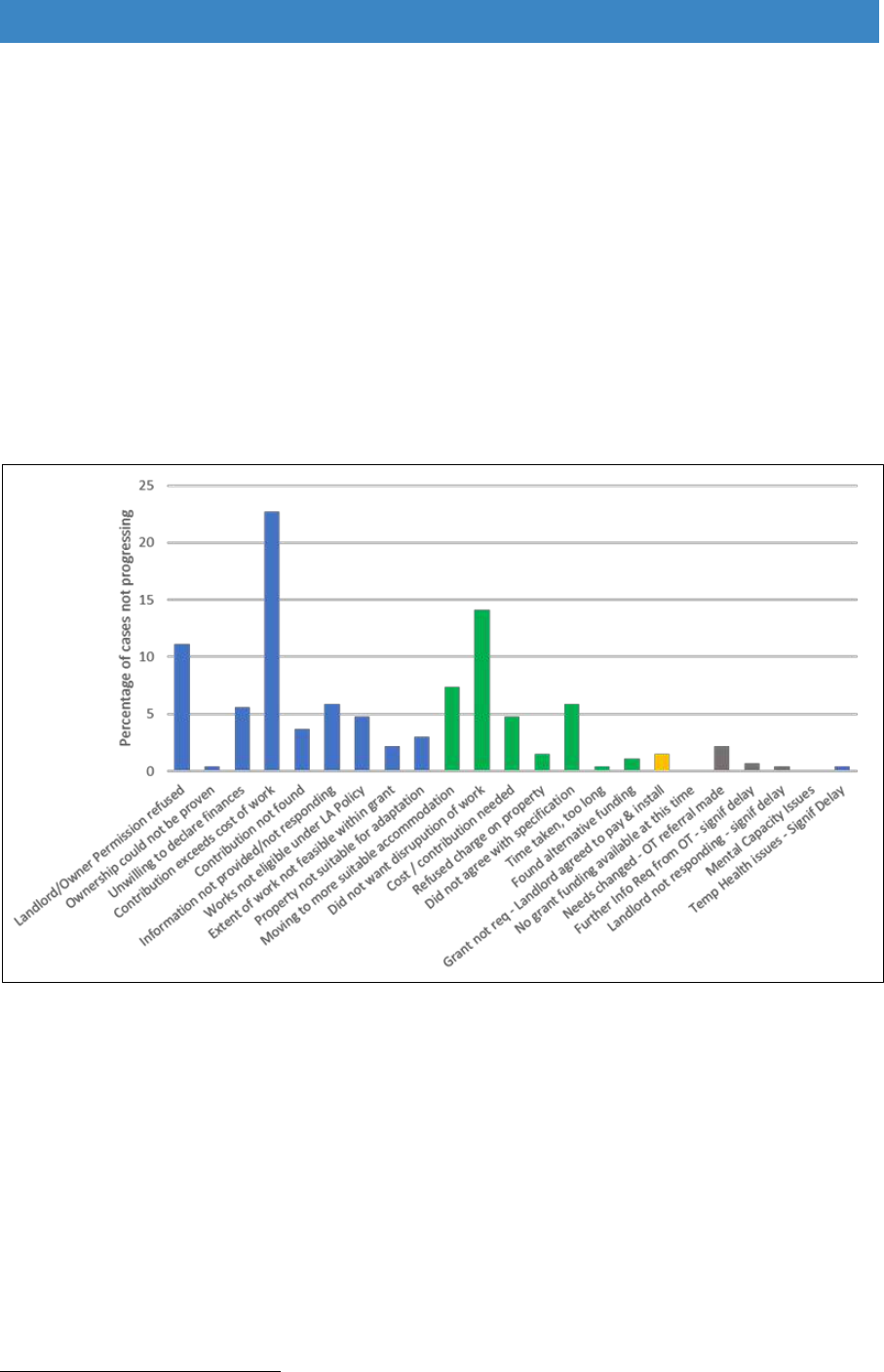

Reasons for exclusion .......................................................................................... 39

Summary - who gets the DFG and who is excluded ............................................. 41

Chapter 5. Types of adaptations and costs ......................................................... 43

Types of impairment ............................................................................................. 43

Impairment of DFG recipients............................................................................... 44

Type of work allowed ............................................................................................ 45

Type of work carried out ....................................................................................... 46

The cost of DFG work........................................................................................... 47

More expensive grants and those over the upper limit of £30,000 ....................... 49

Rehousing as an alternative to expensive grants ................................................. 50

The Means Test.................................................................................................... 51

Land Charges ....................................................................................................... 52

Summary - types of adaptations and costs........................................................... 52

Chapter 6. Costs and benefits to local authorities.............................................. 54

The benefits of adaptations and potential cost savings ........................................ 54

Costs savings of adaptations for children and young people ............................ 57

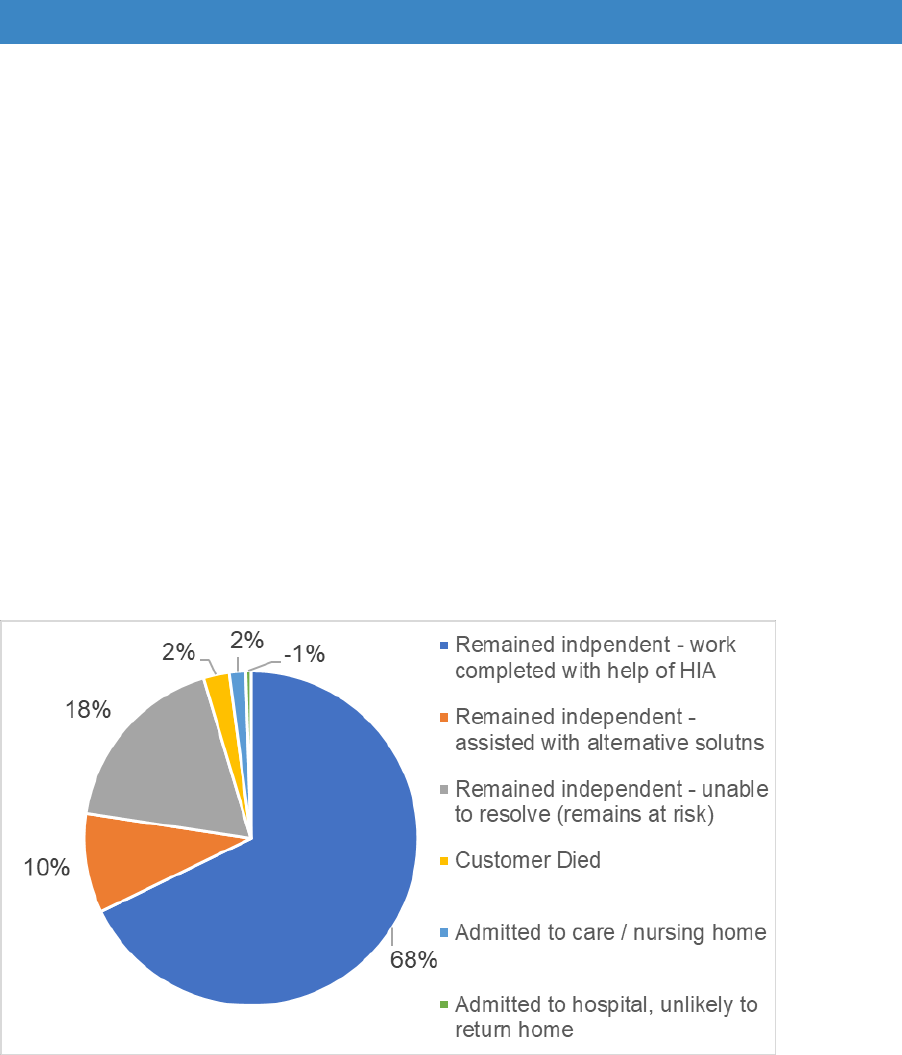

DFG outcome data............................................................................................ 58

The revenue costs of delivering the DFG ............................................................. 59

Independent HIAs ............................................................................................. 60

Staff costs by type of work ................................................................................ 61

Summary - costs and benefits to local authorities ................................................ 63

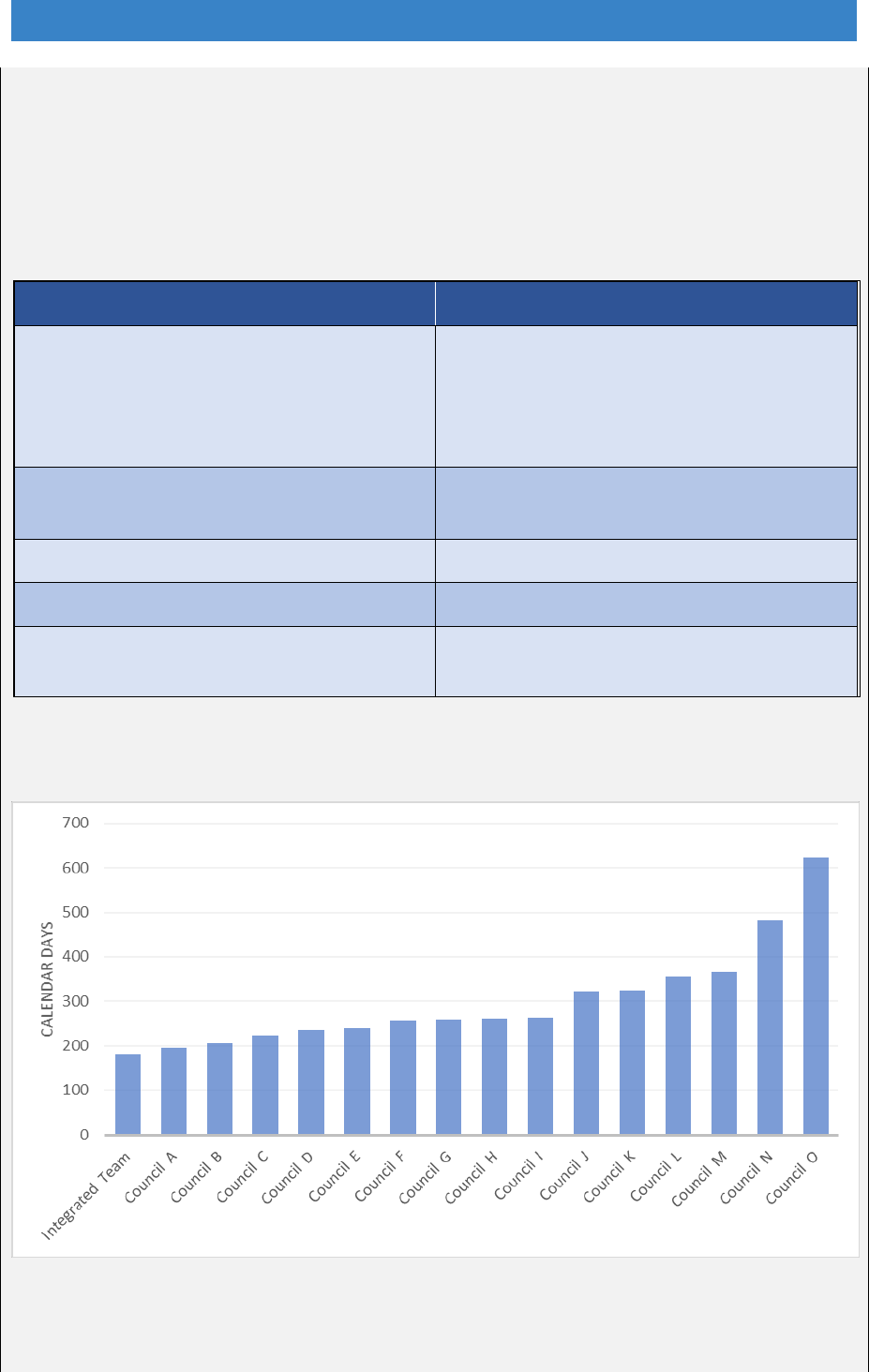

Chapter 7. Processing arrangements and waiting times.................................... 64

Processing arrangements..................................................................................... 64

Time taken to process grants ............................................................................... 68

The effect of RRO policies on timescales ......................................................... 68

The effect of shortages of contractors on timescales ........................................ 69

Effect on disabled and older people, their families and carers.............................. 70

The suitability of the six-month time limit........................................................... 71

The impact of delays ......................................................................................... 72

Summary of issues - processing arrangements and waiting times ....................... 72

Part B How the DFG should change.................................................................... 74

Chapter 8. Introduction to Part B.......................................................................... 75

The structure of Part B ...................................................................................... 76

Chapter 9. The bigger picture ............................................................................... 77

The Disabled Facilities Grant - a hidden service .................................................. 77

4

Disabled Facilities Grant (DFG) and Other Adaptations: Main Report

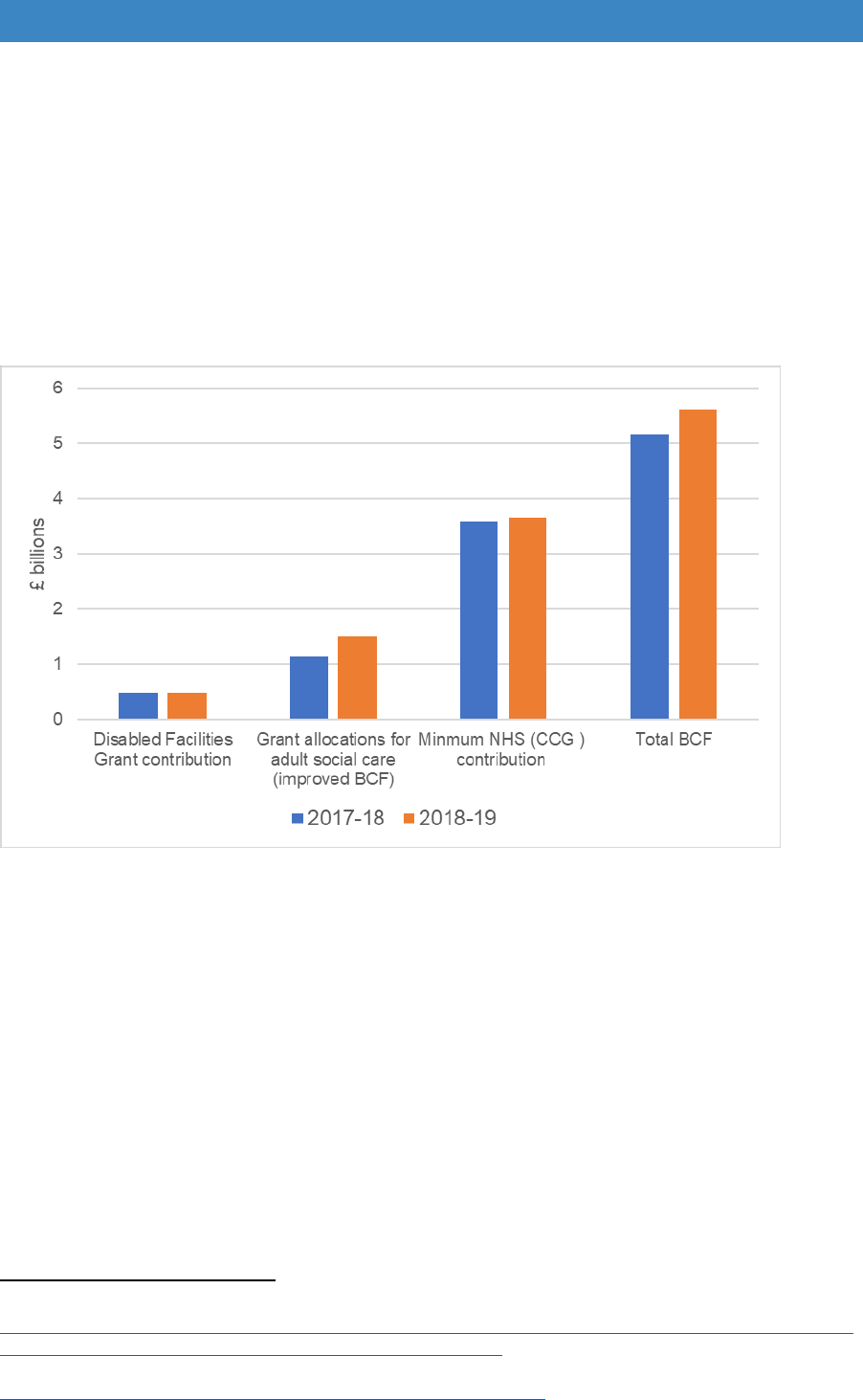

DFG and the Better Care Fund (BCF) .................................................................. 78

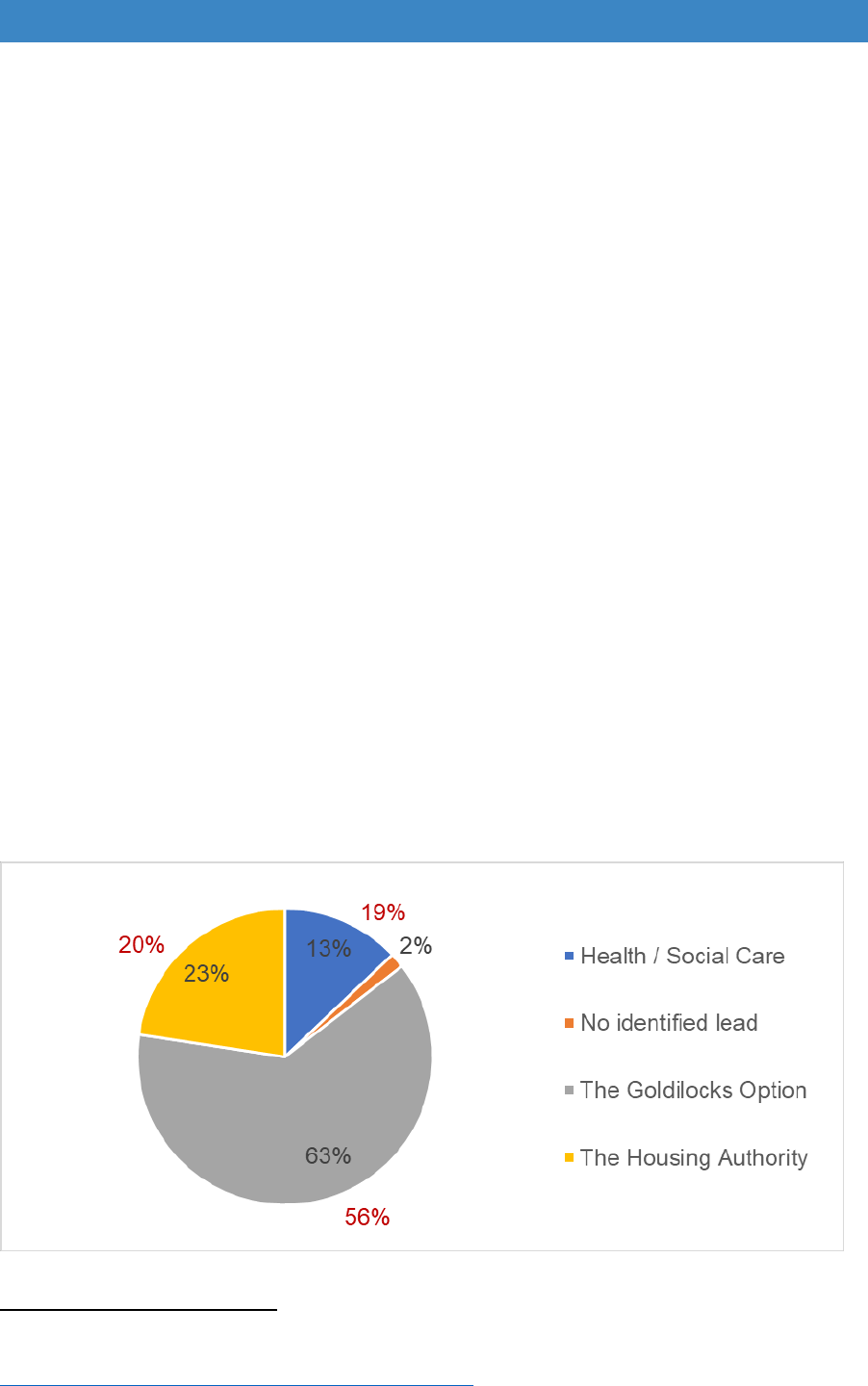

Strategic oversight ................................................................................................ 80

The options for strategic oversight........................................................................ 81

Making partnerships work..................................................................................... 84

National level oversight......................................................................................... 86

Cultural change..................................................................................................... 86

Recognising the broader role of the DFG ............................................................. 87

The need for person-centred services .................................................................. 87

Providing more choice by engaging with housing providers ................................. 88

What should the grant be called? ......................................................................... 89

Recommendations - strategic oversight................................................................ 90

Chapter 10. Local delivery..................................................................................... 91

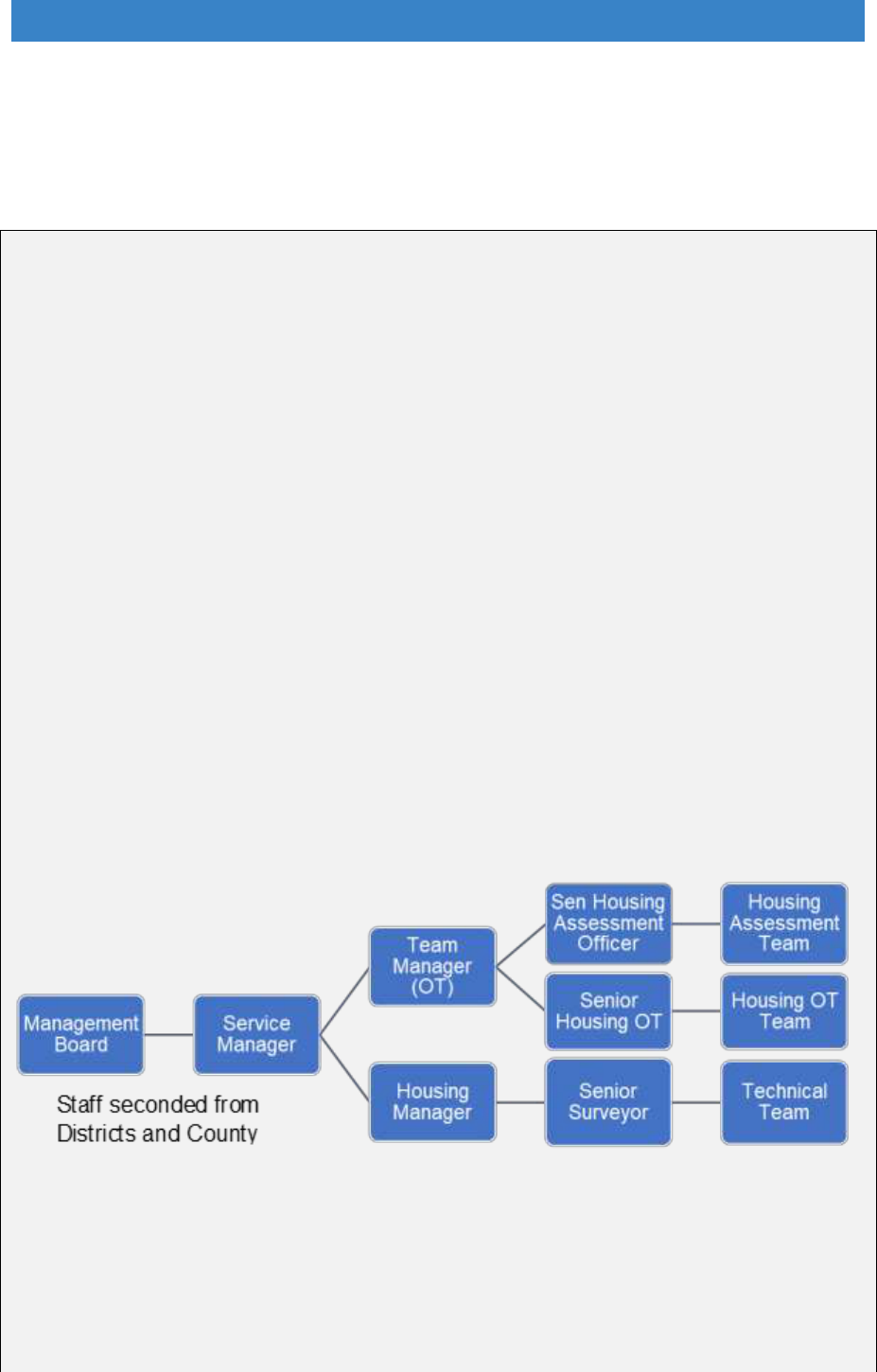

The need for integrated teams.............................................................................. 91

How an integrated team works ............................................................................. 92

Key elements of integrated services ..................................................................... 98

National transformation fund................................................................................. 99

Recommendations – local delivery ..................................................................... 100

Chapter 11. Working better together .................................................................. 101

Establishing local need and handling referrals ................................................... 101

Finding people needing help with their homes ................................................ 101

Information, advice and routing people down the right pathways.................... 104

Effective working................................................................................................. 105

Deciding what is complex and needs occupational therapy input ................... 105

Improving the model for assessing what adaptations are necessary, appropriate,

reasonable and practicable ............................................................................. 107

A collaborative model for the process of determining necessary and appropriate,

reasonable and practicable ............................................................................. 109

Developing a standardised design and construction process for housing

adaptations ..................................................................................................... 111

Communicating with customers, carers and their families .............................. 112

Working in partnership with contractors .......................................................... 113

Delivering better health and social care outcomes ............................................. 114

Examples of preventative services providing savings to health and care........ 114

Dementia and the DFG ................................................................................... 116

Making every contact count (MECC)............................................................... 118

Data collection and reporting .............................................................................. 119

5

Disabled Facilities Grant (DFG) and Other Adaptations: Main Report

Local reporting ................................................................................................ 119

National reporting............................................................................................ 122

Recommendations – working better together ..................................................... 123

Chapter 12. The allocation of resources ............................................................ 124

Current allocations methodology and the need for review .................................. 124

Our approach to the review of resource allocation.............................................. 126

1. The baseline................................................................................................ 128

2. Adjusting this ‘baseline need’ using factors................................................. 132

3. ‘Frail elderly factor’ ...................................................................................... 137

4. The new baseline and impact of adding each factor ................................... 139

Building costs/cost of adaptations................................................................... 149

Summary points – allocation of resources .......................................................... 150

Recommendations - allocation of resources....................................................... 152

Chapter 13. Other funding issues....................................................................... 153

Local contributions to DFG funding..................................................................... 153

Risk sharing contingency fund............................................................................ 154

Joint decision-making and combined funding ..................................................... 155

Personal health budgets ..................................................................................... 156

Recommendations – other funding issues.......................................................... 157

Chapter 14 The means test.................................................................................. 158

Means testing in practice .................................................................................... 159

The options......................................................................................................... 160

Remove the Means test Completely ............................................................... 160

Use of Passporting Only ................................................................................. 162

Update the Existing Means test....................................................................... 163

Adopt the Care and Support Charging Regulations (CSCR)........................... 170

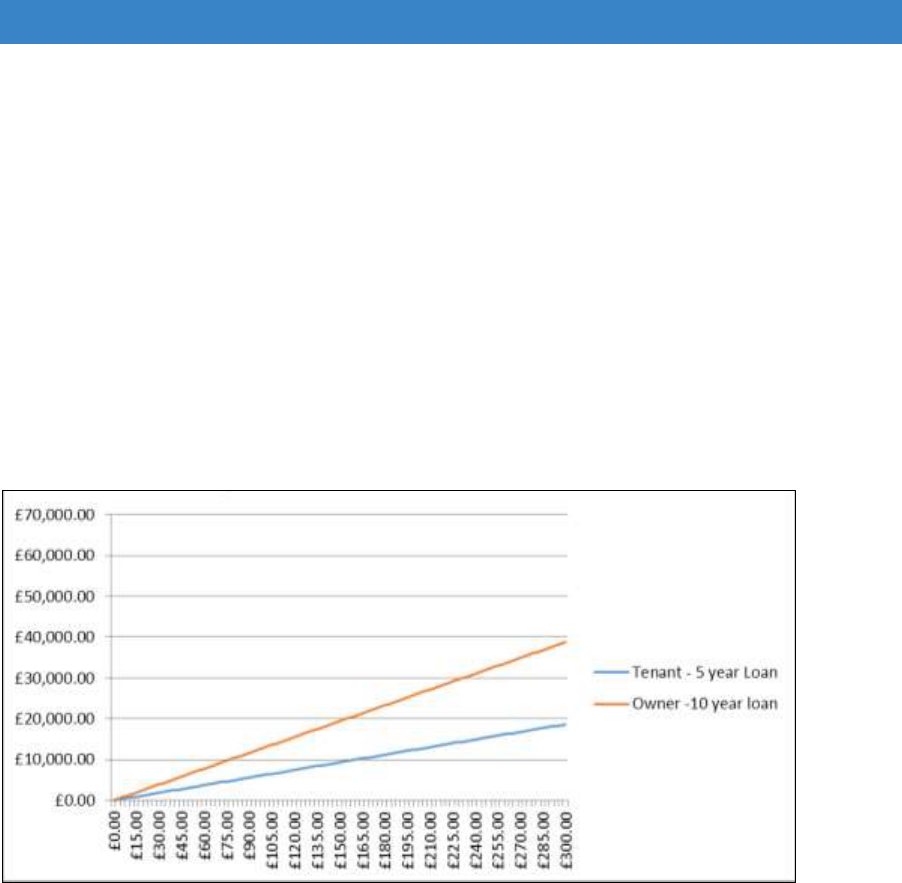

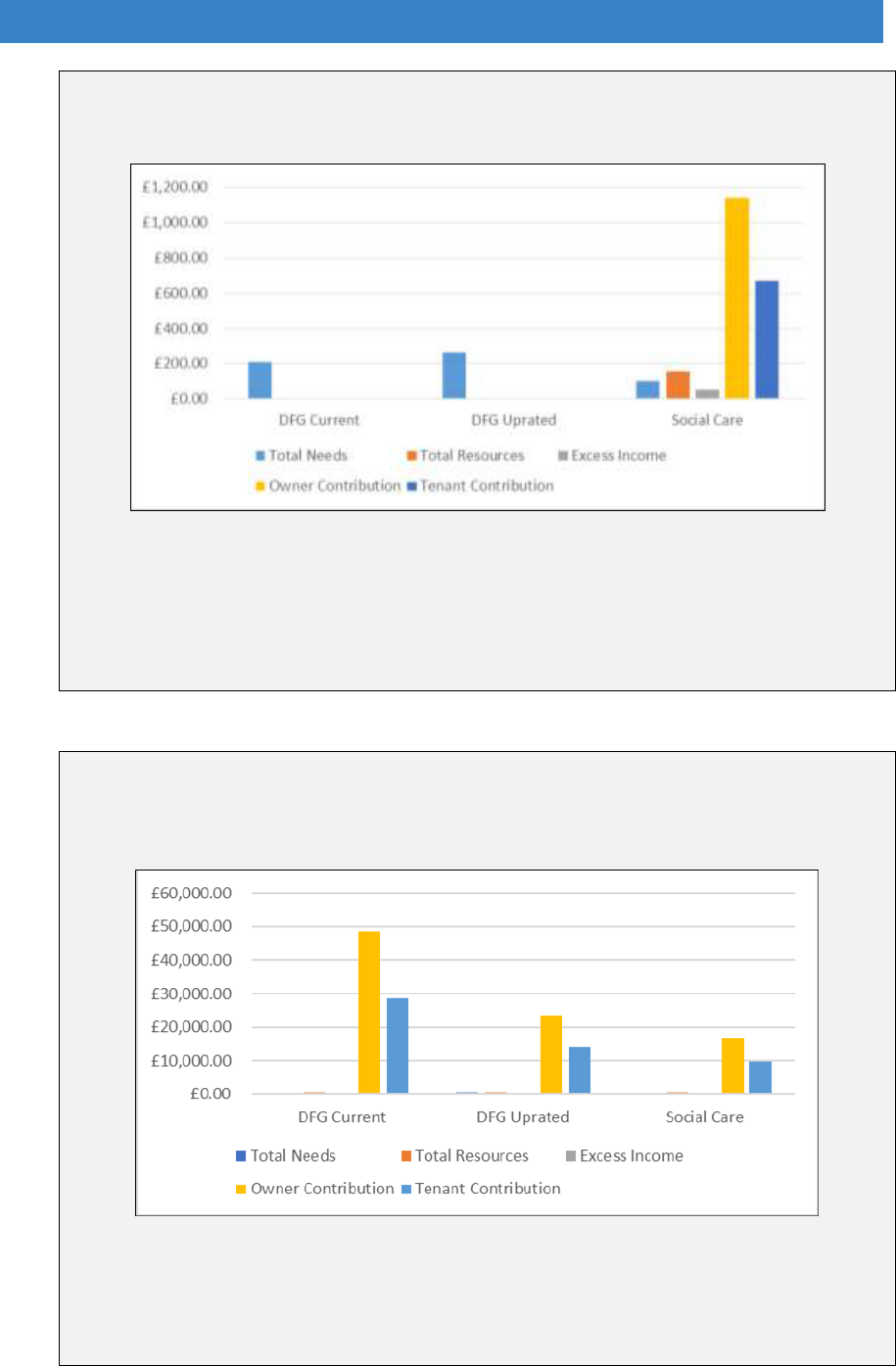

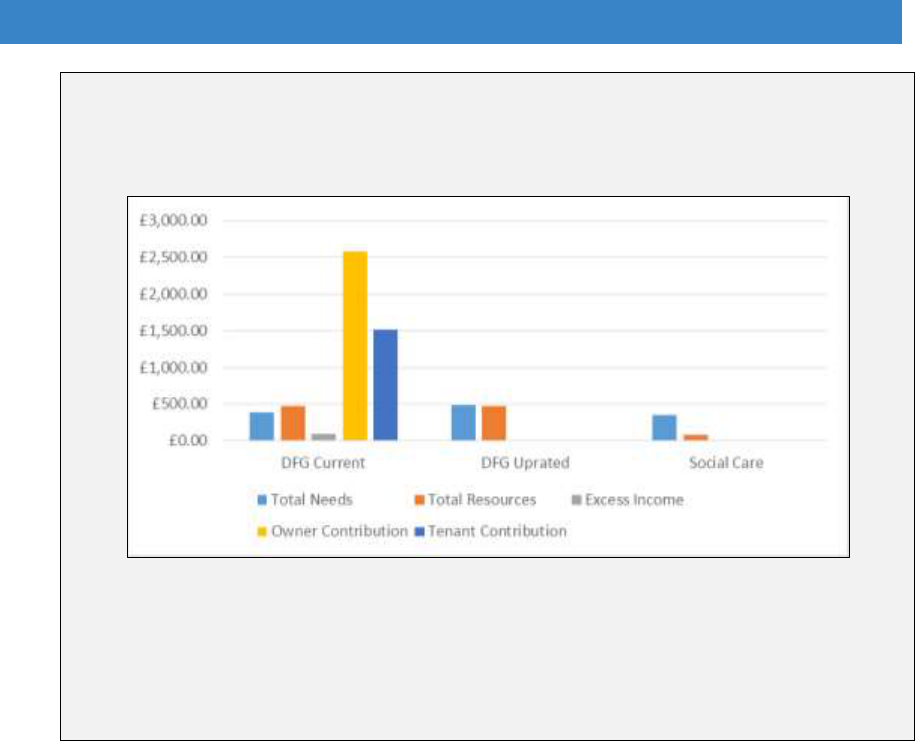

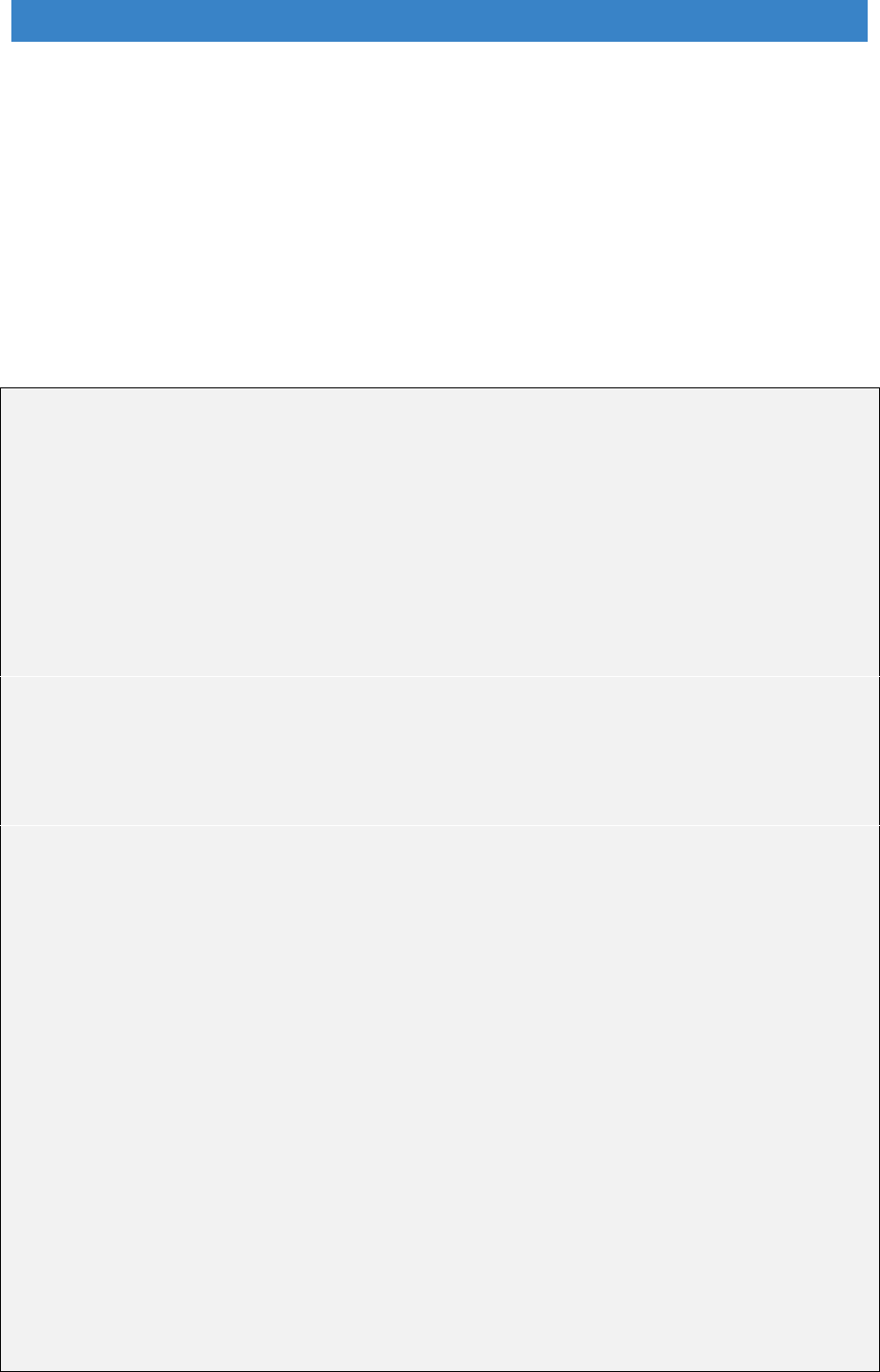

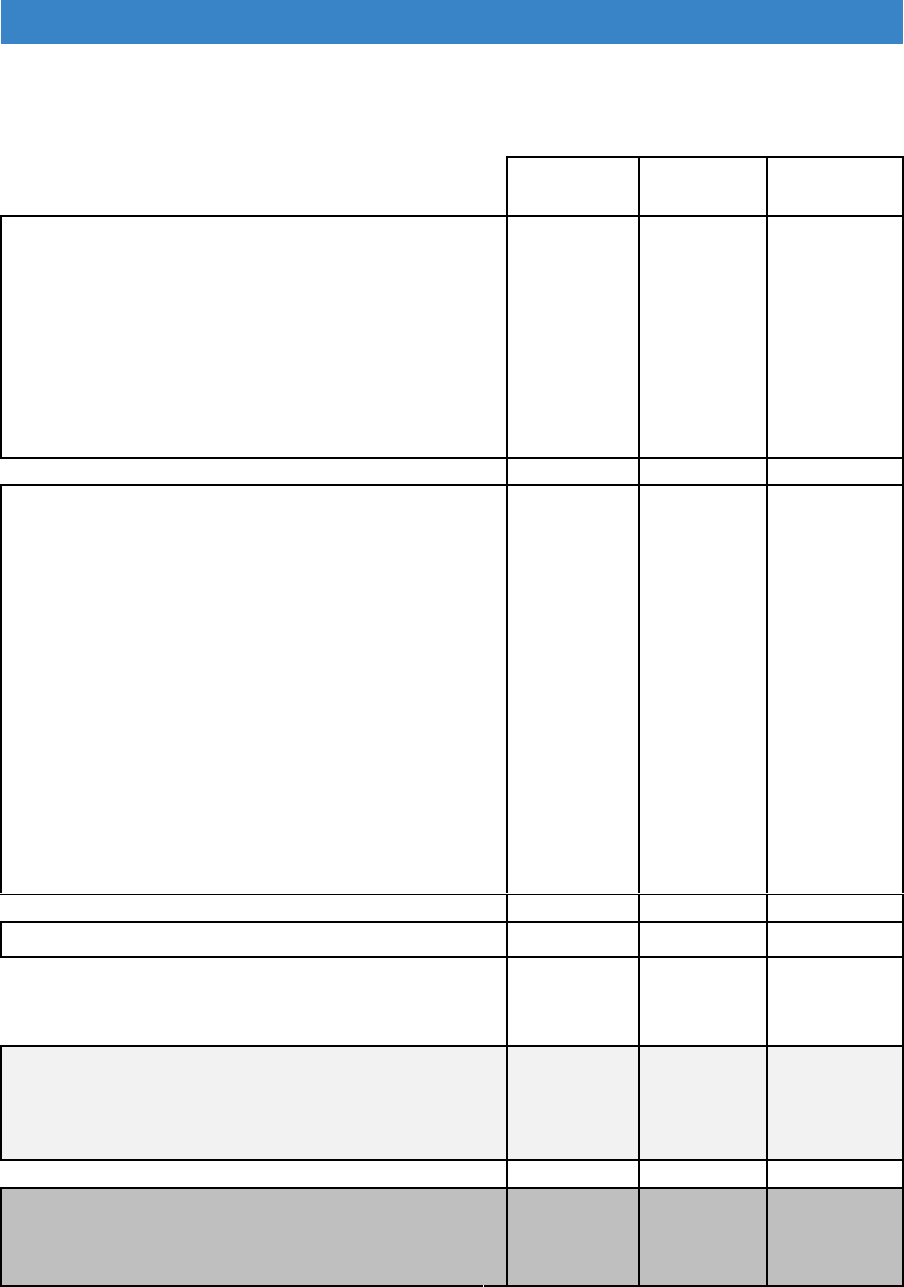

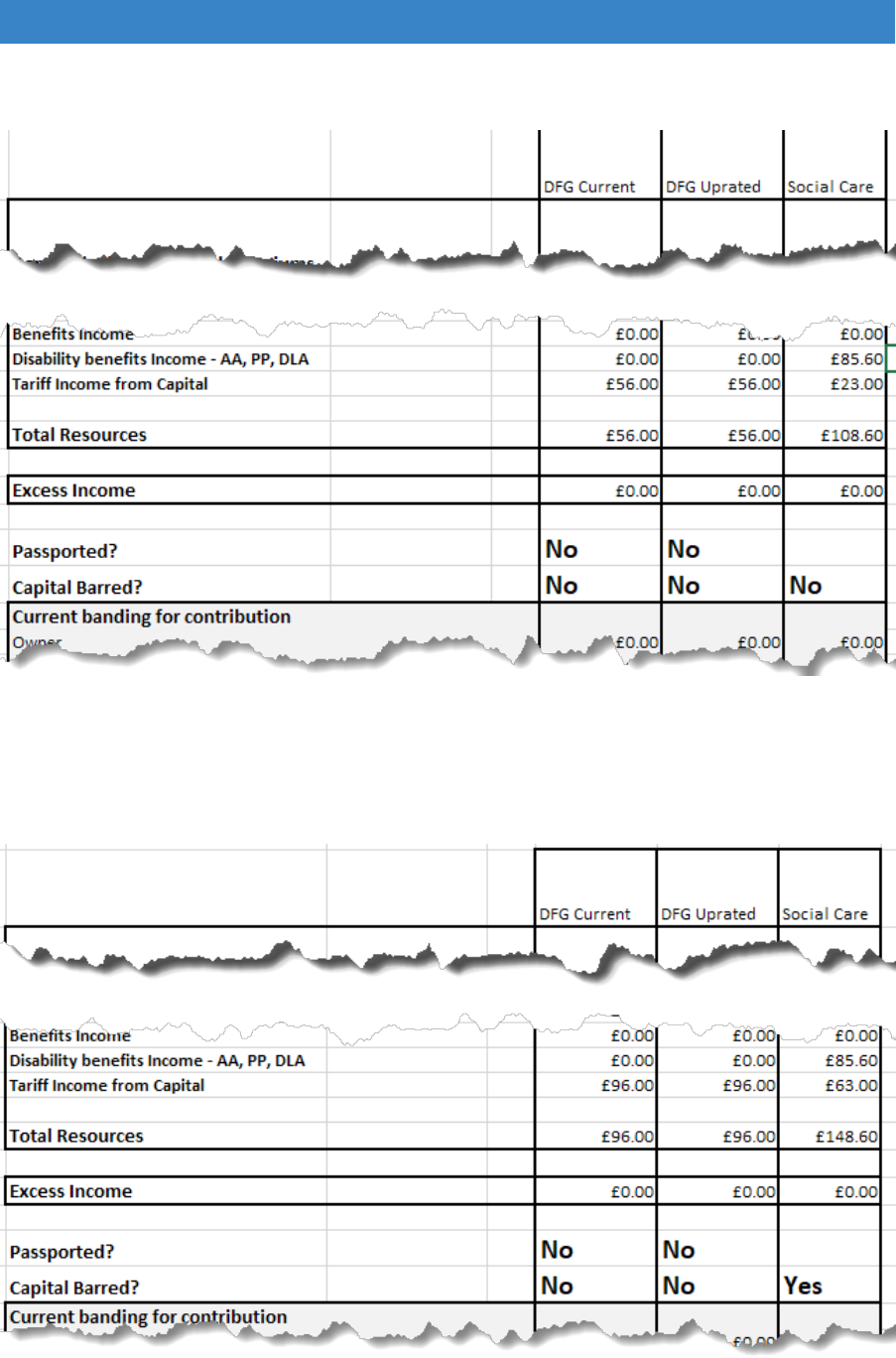

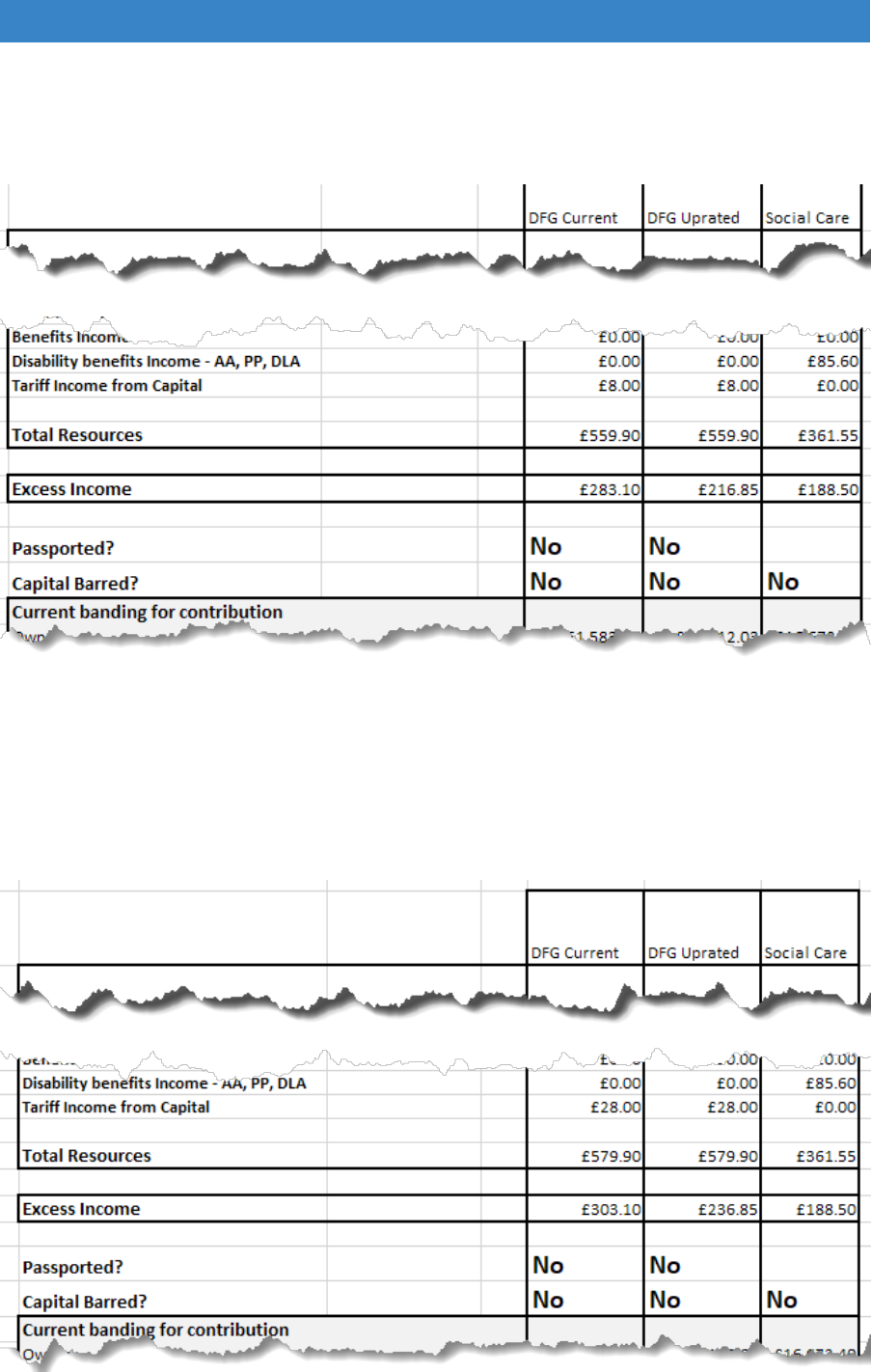

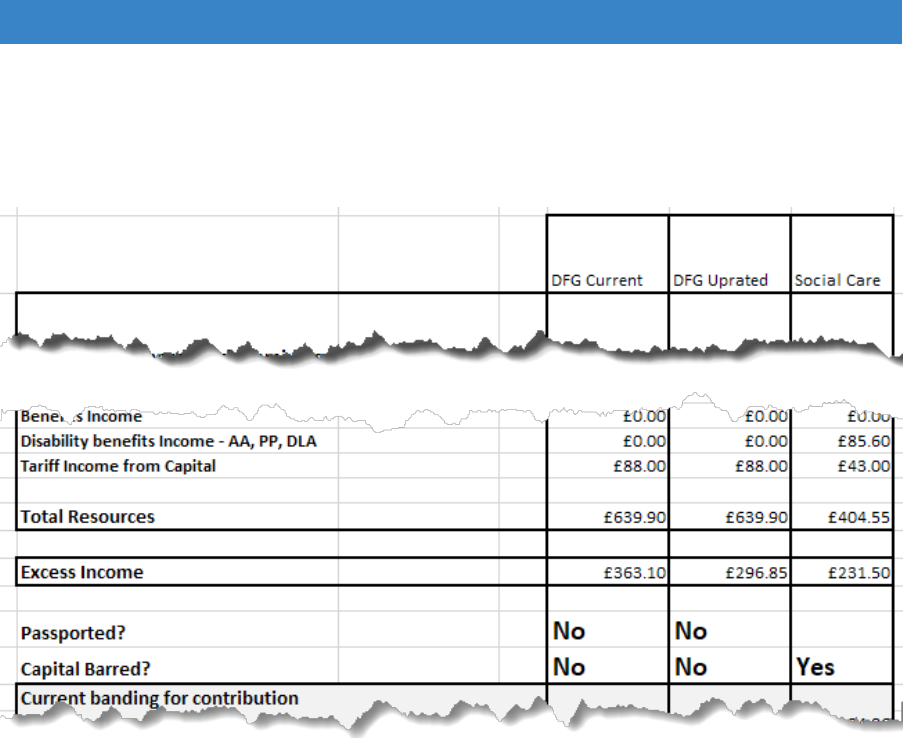

Example scenarios.......................................................................................... 173

Choosing a preferred option ............................................................................... 176

Recommendations – the means test .................................................................. 177

Chapter 15. Regulation and the upper limit ....................................................... 178

The legislation .................................................................................................... 178

The upper limit.................................................................................................... 180

Options for change.......................................................................................... 181

The evidence for change................................................................................. 182

Move away from one size fits all delivery ........................................................ 186

6

Disabled Facilities Grant (DFG) and Other Adaptations: Main Report

Setting a maximum amount ............................................................................ 186

Joint funding, risk sharing and joint decision-making ...................................... 188

Moving rather than adapting ........................................................................... 189

Summary about the upper limit ....................................................................... 190

Regulatory Reform Order (RRO) ........................................................................ 190

Suitability of the 6-month time limit ..................................................................... 194

Other regulation.................................................................................................. 194

The Services and Charges Order.................................................................... 194

Other Funding Considerations ........................................................................ 195

Need for clearer guidance............................................................................... 196

Recommendations – regulation and the upper limit............................................ 196

Chapter 16. Developing a market........................................................................ 197

The current situation ........................................................................................... 197

Procurement ....................................................................................................... 197

Need for Change............................................................................................. 197

Procurement Reform....................................................................................... 200

Value for money, standards and cost benchmarking ...................................... 202

Assistive technology ........................................................................................... 203

Introduction ..................................................................................................... 203

Technology for Ageing Well ............................................................................ 204

Mainstreaming Assistive Technology .............................................................. 206

Cognitive and dementia AT Case Study ......................................................... 209

Using the Data ................................................................................................ 209

User Acceptance............................................................................................. 210

The Downsides ............................................................................................... 210

Assistive Technology and the DFG................................................................. 211

Support for people outside the DFG ............................................................... 211

Market provision.............................................................................................. 213

The role of local authorities ............................................................................. 214

Where people go for information..................................................................... 215

Paying for adaptations .................................................................................... 218

Incentivising home adaptations through the social care cap ........................... 223

Summary – helping people outside the DFG .................................................. 223

Recommendations – developing a market.......................................................... 224

Chapter 17. Tenure and equality......................................................................... 225

7

Disabled Facilities Grant (DFG) and Other Adaptations: Main Report

Inequality of access to the DFG by tenure.......................................................... 225

Home owners.................................................................................................. 226

Registered providers ....................................................................................... 228

Council stock................................................................................................... 230

Social housing generally ................................................................................. 230

Private rented sector ....................................................................................... 231

Adaptations without delay ............................................................................... 232

Common parts grants and the Equality Act....................................................... 232

DFG for adaptations to communal areas ............................................................ 232

Level access in flats with shared facilities ....................................................... 235

Potential cost of providing level access to flats with shared facilities.................. 241

Lifts..................................................................................................................... 241

Housing Health and Safety Rating System (HHSRS) hazards ........................... 243

FOI data.............................................................................................................. 243

Summary points – Section 36 of the Equality Act ............................................... 245

Recommendations – tenure and equality ........................................................... 245

Chapter 18. Summary, conclusions and recommendations ............................ 246

Housing and Health Partnership Board .............................................................. 246

Making the service more visible.......................................................................... 246

Integrating services............................................................................................. 247

Resources .......................................................................................................... 249

The means test................................................................................................... 250

The upper limit.................................................................................................... 251

Regulation .......................................................................................................... 252

Developing a market........................................................................................... 252

Helping people outside the DFG......................................................................... 253

Tenure and equality issues................................................................................. 254

Conclusions ........................................................................................................ 255

Recommendations - overview ............................................................................ 257

Further research and development work ............................................................ 260

The Review Team ................................................................................................. 263

List of organisations contributing to the review ............................................... 264

Appendix............................................................................................................... 267

Appendix 1 - Proposed DFG Metrics .................................................................. 268

Appendix 2 Allocation formula ............................................................................ 269

8

Disabled Facilities Grant (DFG) and Other Adaptations: Main Report

A2.1 Income Deprivation Domain.................................................................... 269

A2.2 Other data sources investigated but not included in the allocations formula

modelling......................................................................................................... 270

Appendix 3 Means Testing ................................................................................. 271

A3.1 Current rates of allowances and premiums............................................. 271

A3.2 Example scenarios - details.................................................................... 272

A3.3 Summary of main differences between the two preferred options .......... 283

References............................................................................................................ 285

9

Disabled Facilities Grant (DFG) and Other Adaptations: Main Report

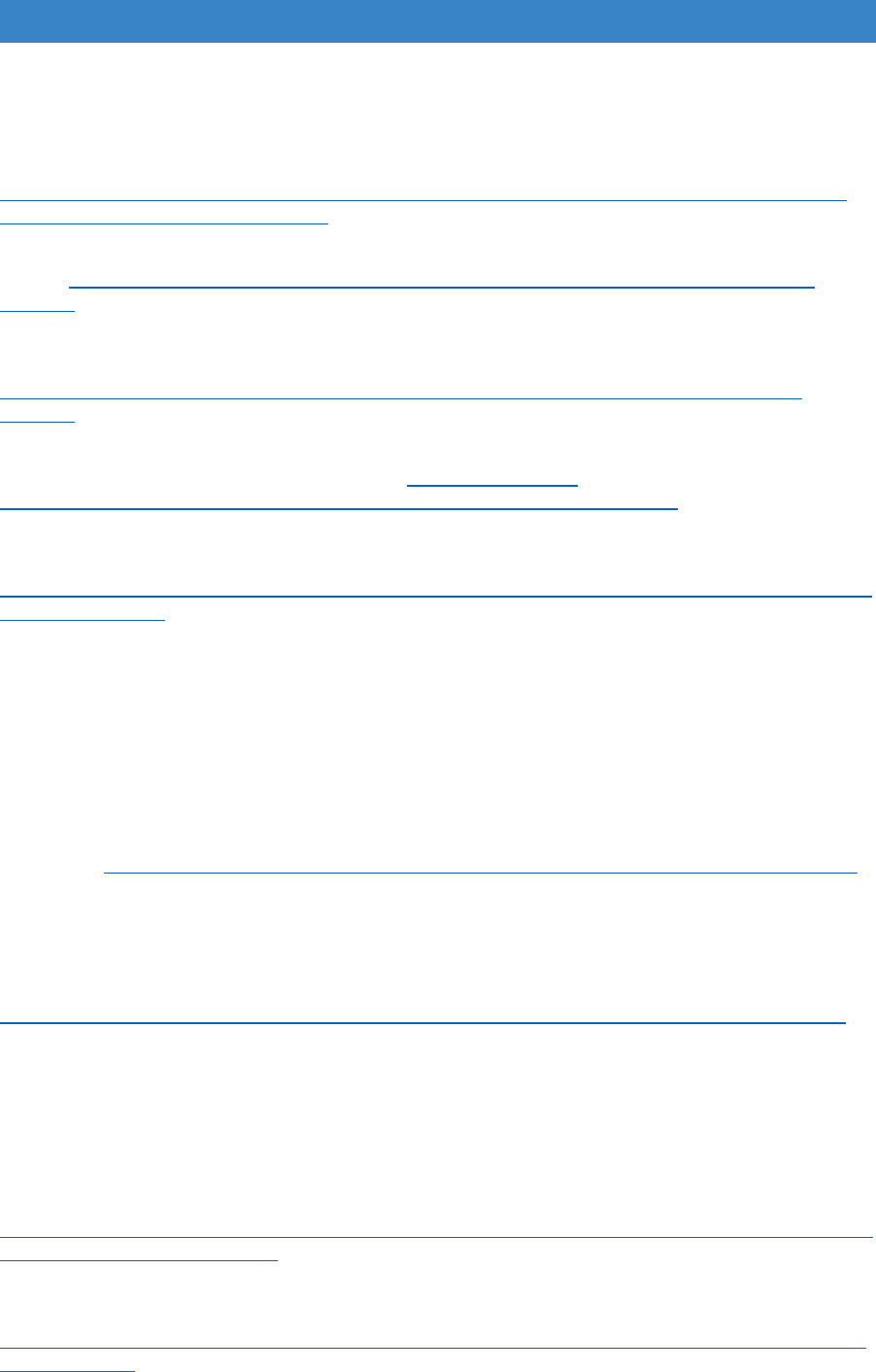

Glossary

We have tried to avoid using acronyms, but you will see some abbreviations in the

text. They have had to be used in tables and diagrams to fit the space.

AA Attendance Allowance

ALMO Arms-Length Management Organisation

BAME Black, Asian and minority ethnic

BCF Better Care Fund

CA Carers Allowance

CSCR Care and Support (Charging and Assessment of Resources) Regulations 2014

CCG Clinical Commissioning Group

DFG Disabled Facilities Grant

DHSC Department of Health and Social Care

DLA Disability Living Allowance

DWP Department of Work and Pensions

ESA Employment and Support Allowance

EHS English Housing Survey

FOI Freedom of Information request

HB Housing Benefit

HIA Home Improvement Agency

HRA Housing Revenue Account

HMPP Home Modification Process Protocol

HWB Health and Wellbeing Board

ICES Integrated Community Equipment Service

IIDB Industrial Injuries Disablement Benefit

IMD Index of Multiple Deprivation

JSNA Joint Strategic Needs Assessment

LAC Looked After Child

MHCLG Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government

NHF National Housing Federation

ONS Office of National Statistics

OT Occupational Therapist

PIP Personal Independence Payment

RCOT Royal College of Occupational Therapists

RP Registered Provider

RRO Regulatory Reform (Housing Assistance) (England and Wales) Order 2002

Note: where web addresses are given in the text, these were live Nov 2018.

10

Disabled Facilities Grant (DFG) and Other Adaptations: Main Report

Chapter 1. Introduction

The aims of this review

1.1 Across England the population is ageing, there are high numbers of disabled

working age adults and rising numbers of families with disabled children. The

majority live in ordinary housing, but most homes are not well designed for

disabled people. In 2014 just 7% of homes (around 1.7 million) had all four basic

accessibility features of level access, flush threshold, downstairs toilet, and

sufficiently wide doorways and circulation space

1

.

1.2 The Disabled Facilities Grant (DFG) is a means tested capital grant which can

contribute towards the cost of adapting a home, for example by installing a

stairlift, creating a level access shower room, widening doorways, providing

ramps and hoists or creating a ground floor extension. However, delivery of the

grant is changing. It is increasingly being used to provide a wider range of

solutions to the problems people face in their home.

1.3 This review is divided into two parts which will:

A. Provide an assessment of how the DFG is currently being used

B. Make evidence-based recommendations about how the DFG should change.

1.4 There are two main aims:

1) To support more people to live in suitable housing so they can stay

independent for longer. Many disabled and older people spend most of their

time in their home and the accessibility, warmth and comfort of that home has

a vital role to play in health and wellbeing. For disabled people of working age,

the home also needs to be a place that makes it easy for them to earn a living.

For families with disabled children the home should enable children to grow,

develop and lead as normal a life as possible.

2) To make the case for more joined-up action across housing, health and

social care. Suitable housing plays a key role in preventing accidents, allowing

swift return from hospital, restoring health and wellbeing, supporting carers and

encouraging independent living. Responsibility for the DFG at local authority

level is often split between different departments and directorates. The review

will look at the need for the DFG to be joined more closely with other services

to provide better support for disabled and older people.

1

Ministry of Housing Communities and Local Government (2016b) English housing survey 2014 to

2015: Housing for older people report, London: MHCLG.

https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/english-housing-survey-2014-to-2015-housing-for-older-

people-report.

11

Disabled Facilities Grant (DFG) and Other Adaptations: Main Report

Why the review is needed

Changes since the last review

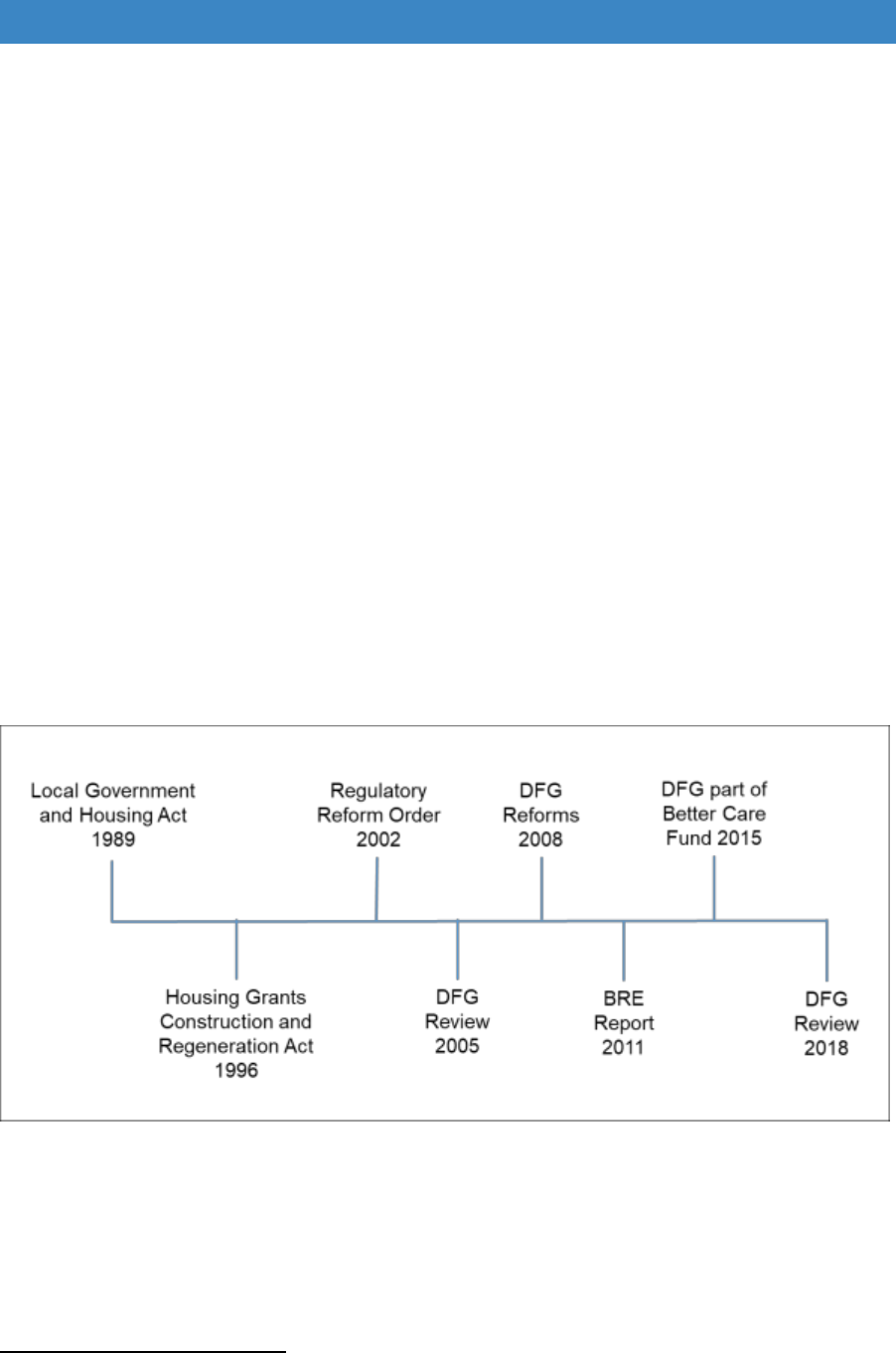

1.5 The Disabled Facilities Grant (DFG) is now nearly 30 years old. It was introduced

in 1989 as one small part of a raft of grants designed to improve the poorest

housing stock. The legislation was reviewed in the early 1990s, and it is the 1996

Housing Grants Construction and Regeneration Act which governs operation of

the DFG today (Figure 1.1). Further changes to introduce more flexibility in the

use of the DFG were brought in with the Regulatory Reform (Housing Assistance)

(England and Wales) Order 2002 (RRO). Over the intervening period, all the

housing renewal and improvement grants that were part of the original legislation

have been discontinued and the only grant that remains is the DFG.

1.6 The DFG is a mandatory grant, which means that it is a legal requirement for

local authorities to provide help to people who meet the eligibility criteria, whether

or not the authority has sufficient budget

2

. These criteria include ensuring that

the works are necessary and appropriate to meet the needs of the disabled

person, and that they are reasonable and practicable given the age and condition

of the property.

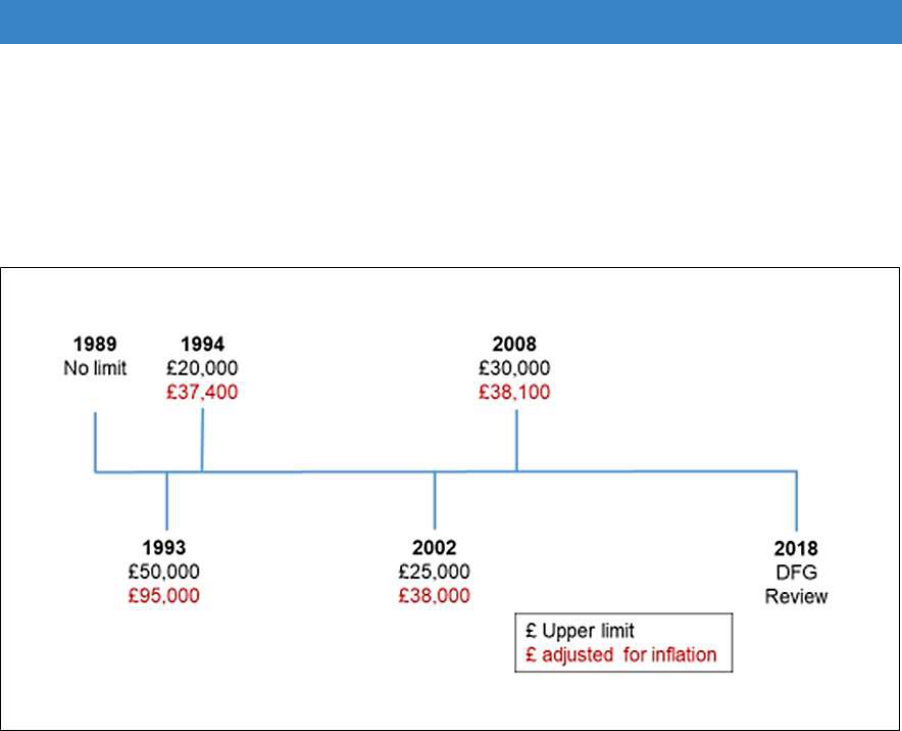

Figure 1.1 DFG Timeline

1.7 The last major review of DFG was in 2005, which immediately led to the removal

of the means test for children and young people aged 18 or under and other

significant changes which came into effect in 2008. These took away the ring

fence on funding; raised the maximum grant limit from £25,000 to £30,000; and

allowed passporting of people on certain mean-tested benefits through the test

2

A high court ruling in 1998 stated that local housing authorities are not entitled to have regard to

their financial resources in determining whether or not to approve an application for a DFG for

purposes within Section 23(1) of HGCRA 1996 (R v Birmingham City Council ex p Taj Mohammed

(1998) Times Law Reports 429, QBD).

12

Disabled Facilities Grant (DFG) and Other Adaptations: Main Report

of resources to remove unnecessary bureaucracy. The 2008 reforms also

allowed more flexibility in the use of the grant, for example: to fast-track grants;

to make homes safe and warm for people being discharged from hospital; or to

help people relocate to more suitable housing. However, not all the

recommendations arising from the 2005 review were implemented. Many of the

remaining issues are dealt with in this review.

1.8 In 2011, the Building Research Establishment (BRE) did an in-depth review of

the means test and the allocation methodology. The formula they developed for

the allocation of resources has been used to distribute most of the additional

central government funding since this date. However, a more recent report on

the DFG suggested that the distribution of resources might need further changes

to provide a more equitable spread

3

.

1.9 Recent and substantial changes to house prices, benefits, retirement ages and

the costs of work mean that the allocation formula, the means test and the upper

limit all need reviewing.

1.10 Over the years there have also been a considerable number of court judgements,

Ombudsman reports and letters of guidance which have had an impact on the

use of the grant and the delivery process. This plethora of different sources of

information needs bringing together to give local authorities a blueprint for

effective operation of the grant.

Changing context

Integration

1.11 The context in which the DFG is delivered has also changed significantly in the

last decade. Although the DFG is about altering the built environment, it is also

about supporting disabled and older people to be independent, enabling carers

to continue their role safely, preventing accidents and helping people to return

from hospital. It therefore crosses the boundaries between housing, health, and

social care

1.12 Reflecting this cross-sector role, in April 2015 the grant became part of a joint

health and social care budget, the Better Care Fund (BCF). Responsibility for

funding the DFG is now held by the Department of Health and Social Care

(DHSC). The Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government

(MHCLG) continues to lead on policy and the distribution of funding.

1.13 At national level there is beginning to be a clearer focus on the integration of

housing with health and care services. In March 2018 an updated Memorandum

of Understanding on Improving Health and Care Through the Home was signed

3

Mackintosh, S. and Leather, P. (2016) The Disabled Facilities Grant Before and after the

introduction of the Better Care Fund, Glossop: Foundations.

http://www.foundations.uk.com/media/4665/dfg-report-final-interactive-converted-draft-6-small.pdf

13

Disabled Facilities Grant (DFG) and Other Adaptations: Main Report

by all the principal national organisations concerned with the delivery of housing,

health and care services.

1.14 The way services are delivered at local level is also changing, driven by the 2014

Care Act, Sustainable Transformation Planning for health and social care, and

local authority restructuring and devolution. Good practice is evolving as

transformation and service integration takes place. The review looks at the

different models that are developing and how this is beginning to join-up formerly

separate services and provide more holistic solutions for disabled and older

people.

1.15 New local structures at strategic level may be needed to ensure that this best

practice gets properly embedded across the country to enable disabled and older

people get access to fast and effective services no matter where they live.

Increased resources

1.16 Since the DFG became part of the BCF there has been a significant increase in

central government resources. In 2014/15 central government contributed

£220m, but by 2017/18 this had more than doubled to £473m in total. There is a

need to show how this has impacted on local funding contributions and whether

there has been a significant increase in the number of people helped to remain

independent each year.

Ageing population and rising numbers of disabled people

1.17 The impact of the ageing population in the UK has begun to be much more

apparent. The pressures on health and social care have been increasing,

particularly in the winter of 2017/18 when there were delays in accident and

emergency departments and a shortage of hospital beds. Research is beginning

to demonstrate the role adaptations play in reducing accidents, enabling faster

hospital discharge, providing support to carers, and enabling people to remain

living in their own homes for longer, rather than needing residential care. The

need for services that wrap around the patient or service user, rather than them

having to seek out relevant services from a myriad of different sources is also

becoming better understood, which will affect the findings of the review.

Changing expectations and impact of technology

1.18 The review also needs to consider the evidence about what people feel about

their homes, the type of adaptations that they want to see provided and how

this might affect how the DFG could develop in future. Expectations are

changing and there are new materials and advances in information technology

and artificial intelligence which are rapidly being incorporated into people’s

homes. The DFG needs to evolve if it is to remain relevant for the next decade

and beyond.

Changes in tenure

1.19 When the DFG was originally conceived it was mainly for people who were low

income home owners living in poorer housing. Since then, registered provider

tenants (housing associations) have begun to use the DFG in much greater

14

Disabled Facilities Grant (DFG) and Other Adaptations: Main Report

numbers, but the DFG it is not used by tenants in the council stock who have a

separate funding stream through the housing revenue account.

1.20 The mix of tenures is changing with increasing numbers of disabled people now

in the private rented sector. Adaptations in the private rented sector are more

difficult to deliver as people often have short-term tenancies. This report makes

some suggestions about better ways of working with landlords. Tenure issues

are not explored in depth and need further review.

Problems with service delivery

1.21 Over the years there have been continual complaints about DFG delivery. A CLG

Committee report on Housing for Older People pointed out that the DFG followed

‘a clunky process’ and that waiting times varied significantly between authorities

4

.

A report by the Equality and Human Rights Commission also said that grant

delivery was too slow

5

.

1.22 The 2005 review pointed out the lack of strategic oversight, the paucity of

evaluation information and the absence of effective performance targets. It also

made the point that part of the strategic challenge was to shift the thinking from

‘welfare’ to ‘investment’ so that decisions were not made on the basis of lowest

cost but instead looked at the long-term health and wellbeing of the disabled

person and their family. These issues are key areas that this review addresses.

The focus of the report

1.23 This review examines the current situation and shows some of the ways in which

the grant might not be working as well as it might. However, the emphasis is on

ways in which DFG delivery could change in future and how it can move from

being a stand-alone service to being part of a package of provisions to help

people remain independent. It is a practical review with detailed information

about new ways of working that could drive service change. It also uses evidence

to provide options for Government about future allocation of resources and

means testing.

1.24 Throughout the report, the focus is on the disabled or older person and how they

can be put at the centre of service provision. The report considers what would

make it easier for them, and their families, to find their way through what can be

confusing service pathways. It also considers how those who are not eligible for

the DFG, or chose not to use this funding route, might go about getting advice,

4

Communities and local Government Committee (Feb 2018) Housing for older people: Second report

of session 2017-19, London: House of Commons.

https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmcomloc/370/370.pdf.

5

Equalities and Human Rights Commission (2018) Housing and disabled people: Britain’s hidden

crisis. https://www.equalityhumanrights.com/sites/default/files/housing-and-disabled-people-britains-

hidden-crisis-main-report.pdf.

15

Disabled Facilities Grant (DFG) and Other Adaptations: Main Report

information and support to create a home environment that helps them remain

active and independent.

1.25 Prevention is a major issue. Many services are not delivered in an optimal way

because they are dealing with people at crisis point. The DFG has a key role to

play in prevention as providing adapted housing when people are first

experiencing difficulties is much more effective long-term than reacting when

they have a serious injury or have become very frail. The review will look at how

this preventative role might be delivered more effectively.

1.26 The report only covers the DFG in England. The legislation and arrangements

for providing adaptations are different in the other parts of the UK. However,

where lessons can be drawn from other jurisdictions these will be mentioned in

the report.

16

Disabled Facilities Grant (DFG) and Other Adaptations: Main Report

Chapter 2. Methodology

The review

2.1 There are two main parts to the review, each with several components:

Part A: How the DFG is used currently

DFG funding

Who receives the grant

Types of adaptations and costs

Costs and benefits to local authorities

Processing arrangements and waiting times

Part B: How the DFG should change

The bigger picture

Local delivery

Working better together

Allocation of resources

Funding

The means test

Regulation and the upper limit

Developing a market

Tenure and equality

Methodology

2.2 The review took place over a very short period: February-May 2018. The team

conducting the review already had a depth of understanding about the DFG.

They had worked on previous reviews or had been involved in national or local

service improvement. They understood the variation in delivery across the

country, particularly the differences in operation between unitary and county

authorities. They knew the data sources available, had carried out evaluation of

delivery methods, and examined the evidence about the outcomes of

adaptations. Although the methodology was inevitably constrained by the

restricted time frame, the team was able to access a considerable amount of

national and local evidence and consult a wide range of organisations. Sources

of evidence included:

Analysis of data from LOGASnet returns made annually by local authorities

to the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government combined

with data from a series of Freedom of Information requests. This gave a

17

Disabled Facilities Grant (DFG) and Other Adaptations: Main Report

national picture of annual budgets, the value of work, information on who

receives the grants, time scales, costs of work and type of work carried out.

Three consultation events were held, each with about 70 participants from

local authorities, home improvement agencies and other organisations. An

online survey provided further feedback with responses from 234 people.

There was almost equal representation from people working in occupational

therapy roles (44% online) and those in housing (43% online). Opinions were

obtained relating to key aspects of the review, including: how the means test

might be reformed; whether the upper limit should be changed; how best to

link the DFG to health and social care; effective methods of delivering the

grant; and how to help people outside of the DFG.

The review also drew on the findings of previous consultation events

held by Foundations, the Home Adaptations Consortium and the Royal

College of Occupational Therapists (RCOT) such as: the DFG Summit

December 2016; DFG Champions events over the period 2015-17; and

comments on the DFG Champions Facebook page.

Means test - The review considered the existing means test and compared it

with means tests being used for state benefits (both legacy and those being

introduced) and social care. The methods and results of assessing the levels

of income needed for recipients, the methods by which earnings, income and

capital are used to determine resources and the ways in which those are used

to determine eligibility were all examined. These were modelled against a

number of household types using a model derived from Ferret’s Future

Benefits Model (FFBM) which enabled outcomes to be compared. The effects

of bringing the existing means test in line with the parameters used in other

current means testing was considered, allowing a number of options to be

proposed.

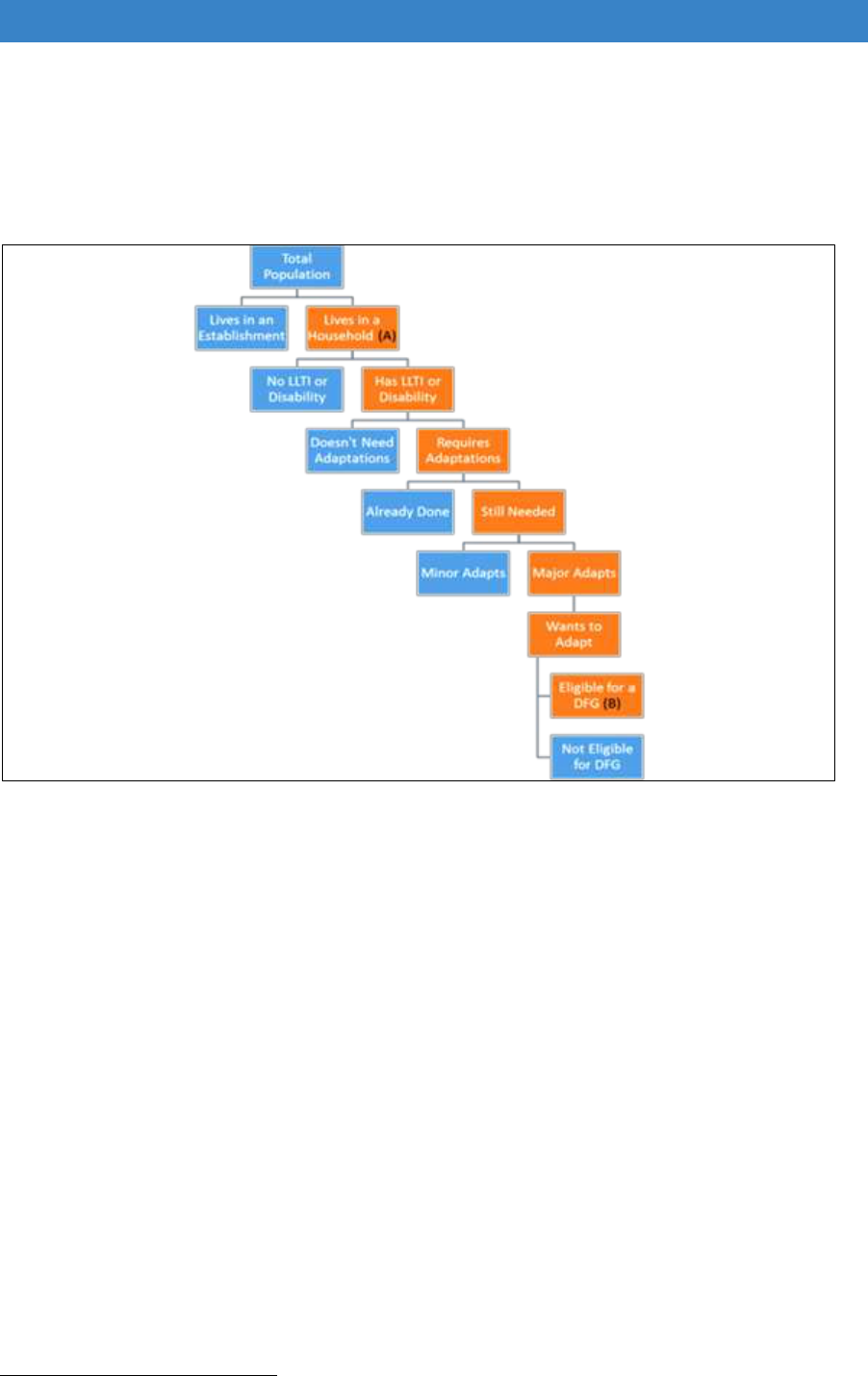

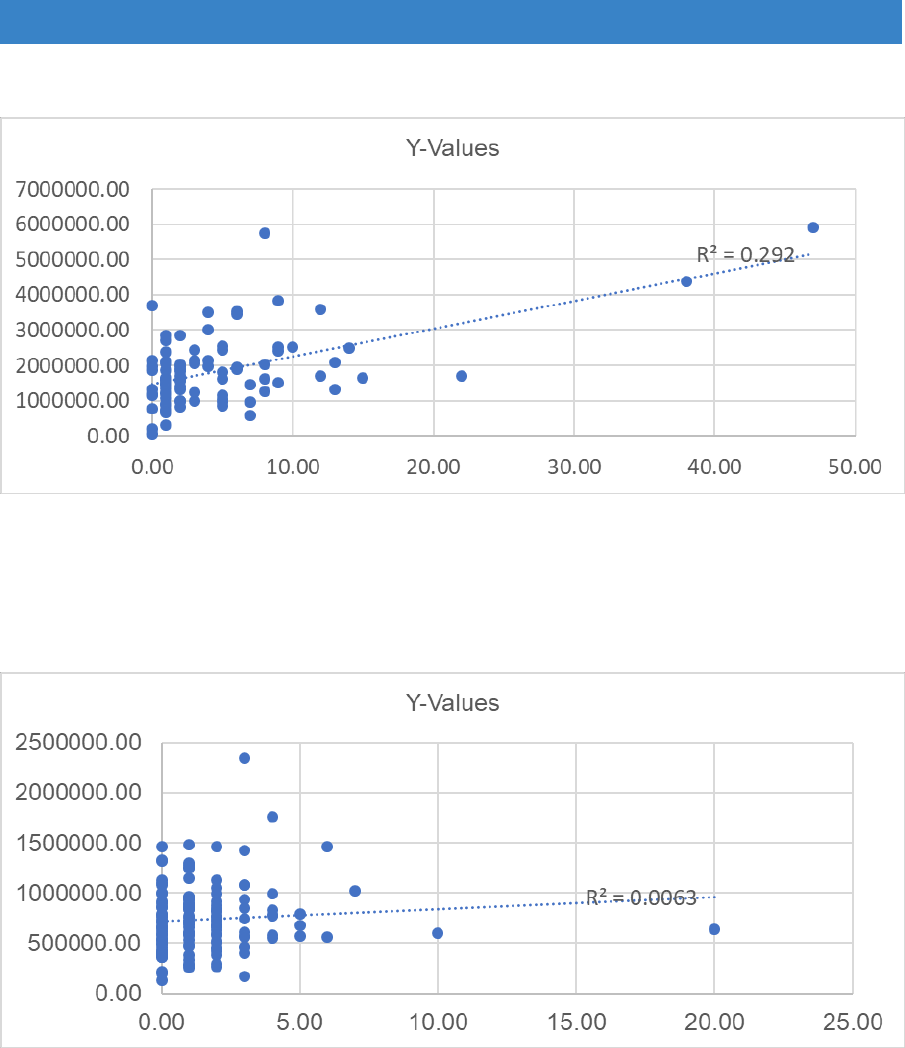

Allocations methodology - the starting point for the review of the allocations

methodology was to create a baseline of the number of people within the local

authority or region who could potentially benefit from adaptations to their

home and then add in ‘adjustment’ factors one by one to examine the

cumulative effect of each stage on the allocation of funds (using 2016/17

funding levels); this helped determine where the greatest shifts in the

distribution of allocations might occur. All adjustment factors, which were

considered suitable proxy indicators of DFG demand, were given equal weight

to help assess their impact. Due to the timescale of this project, the review

focussed on two regions; London, which is very diverse, and Yorkshire and

Humberside, which has a mix of rural and urban authorities. As with the

previous BRE review in 2011, it was considered imperative that the data

available for the proxy indicators of DFG need should meet specific criteria;

simplicity, transparency, be readily accessible, be fair, and provide

sustainability over the medium-term (at least 5 years) but be responsive to

changes in the population and their circumstances.

Interviews with staff from selected local authorities demonstrating

aspects of good practice in grant delivery. These provided more detail

18

Disabled Facilities Grant (DFG) and Other Adaptations: Main Report

about budgets, operating costs, sources of income and management

structures.

Collaboration with other researchers conducting parallel lines of inquiry

provided further information, including: a pilot study of DFG-funded bathroom

adaptations being conducted in Nottingham

6

; minor adaptations research

being carried out by the Royal College of Occupational Therapists and the

Housing LIN

7

; and a study of good practice in the delivery of adaptations to

older people by the Centre for Ageing Better and Care & Repair England

8

.

Meetings with representatives of the national organisations providing

support to local government and the housing association sector were held to

discuss how DFG delivery and oversight might change and to determine how

it might be better joined up with other health and social care services. One

meeting was done in conjunction with the researchers involved in the study of

minor adaptations.

Meetings with the private market sector, combined with online searches

and a short literature review, looked at how the DFG could evolve to embrace

new products and materials and how more people could be helped outside of

the DFG.

Telephone and email contact with academic and policy staff in other parts

of the UK enabled the team to gain insights into alternative methods of DFG

delivery and effective integration of the DFG with health and social care

services.

A short review of the academic, policy and practice literature provided

additional material to determine what disabled and older people want to see in

terms of adaptations and DFG reform.

2.3 The first part of the report, Part A, looks at the evidence relating to the current

situation and the need for change, with a summary of the main findings at the

end of each chapter. In the second section, Part B, these findings are used to

assess the options for to improve services, with a list of recommendations at the

end of each chapter. The main findings and recommendations are brought

together at the end of the report.

6

Whitehead, P., James, M., Belshaw, S., Dawson, T., Day, M. and Walker, M. (2016) Bathing

adaptations in the homes of older adults (BATH-OUT): Protocol for a Feasibility Randomised

Controlled Trial (RCT) BMJ Open. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013448.

7

Royal College of Occupational Therapists (In Press) Adaptations without delay: a guide to thinking

about and delivering adaptations differently. London: Royal College of Occupational Therapists.

8

Adams, S. and Hodges, M. (2018) Adapting for ageing: Good practice and innovation in home

adaptations, London: Centre for Ageing Better. https://www.ageing-

better.org.uk/sites/default/files/2018-10/Adapting-for-ageing-report_CfAB_0.pdf.

19

Disabled Facilities Grant (DFG) and Other Adaptations: Main Report

Part A

How the DFG is used currently

20

Disabled Facilities Grant (DFG) and Other Adaptations: Main Report

Chapter 3. DFG funding

Funding sources and trends

3.1 Information on DFG budgets and spending nationally comes from two main

sources: the annual returns made by local authorities to central government

(LOGASnet); and Freedom of Information requests (FOIs) by Foundations.

LOGASnet returns have become less complete over the last few years (only

returned by 66% of authorities in 2016/17), but they are still one of the best

sources of information at national level

9

. The returns for 2016/17 included some

additional questions on the use of discretionary grants and the time taken to

process cases.

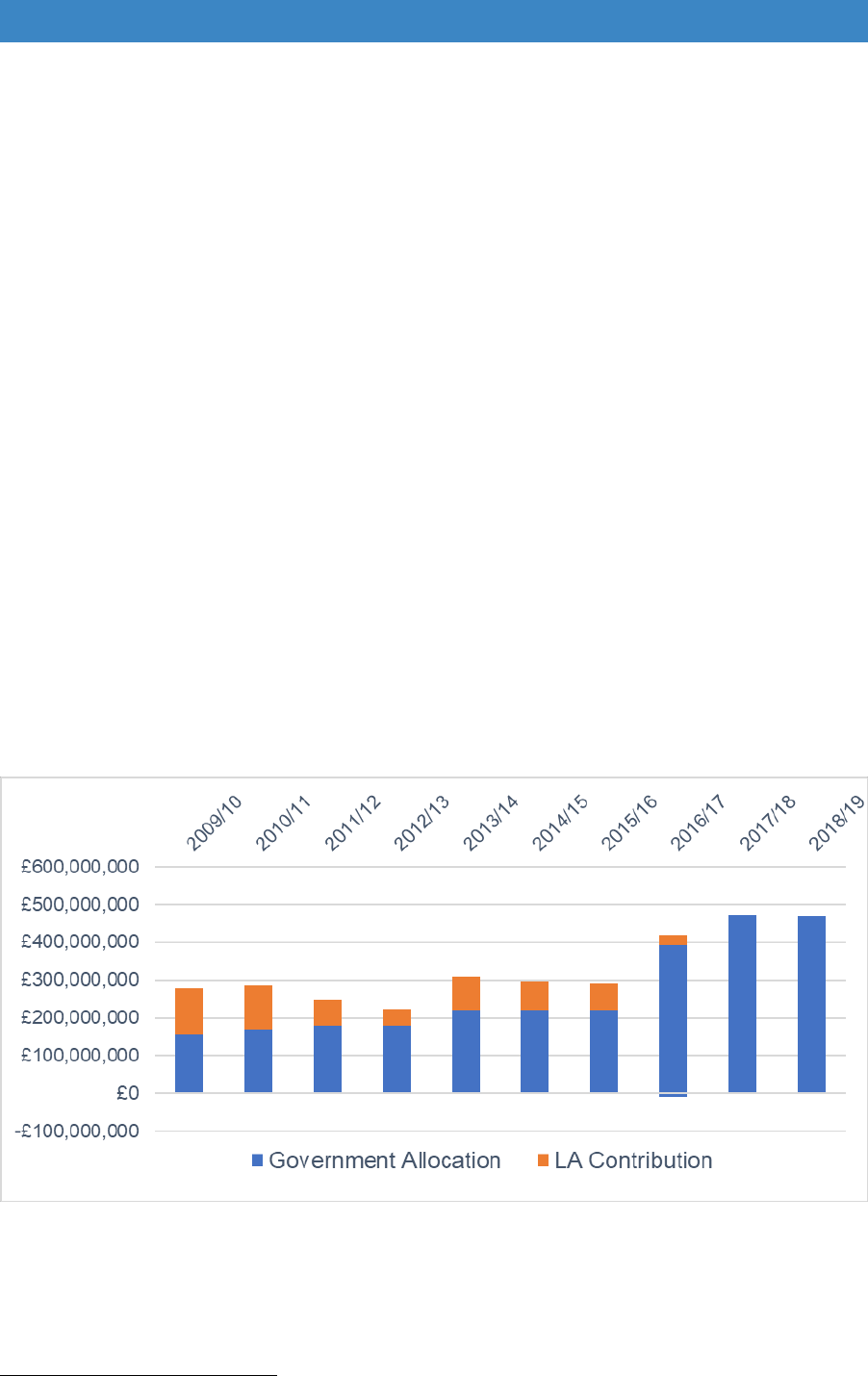

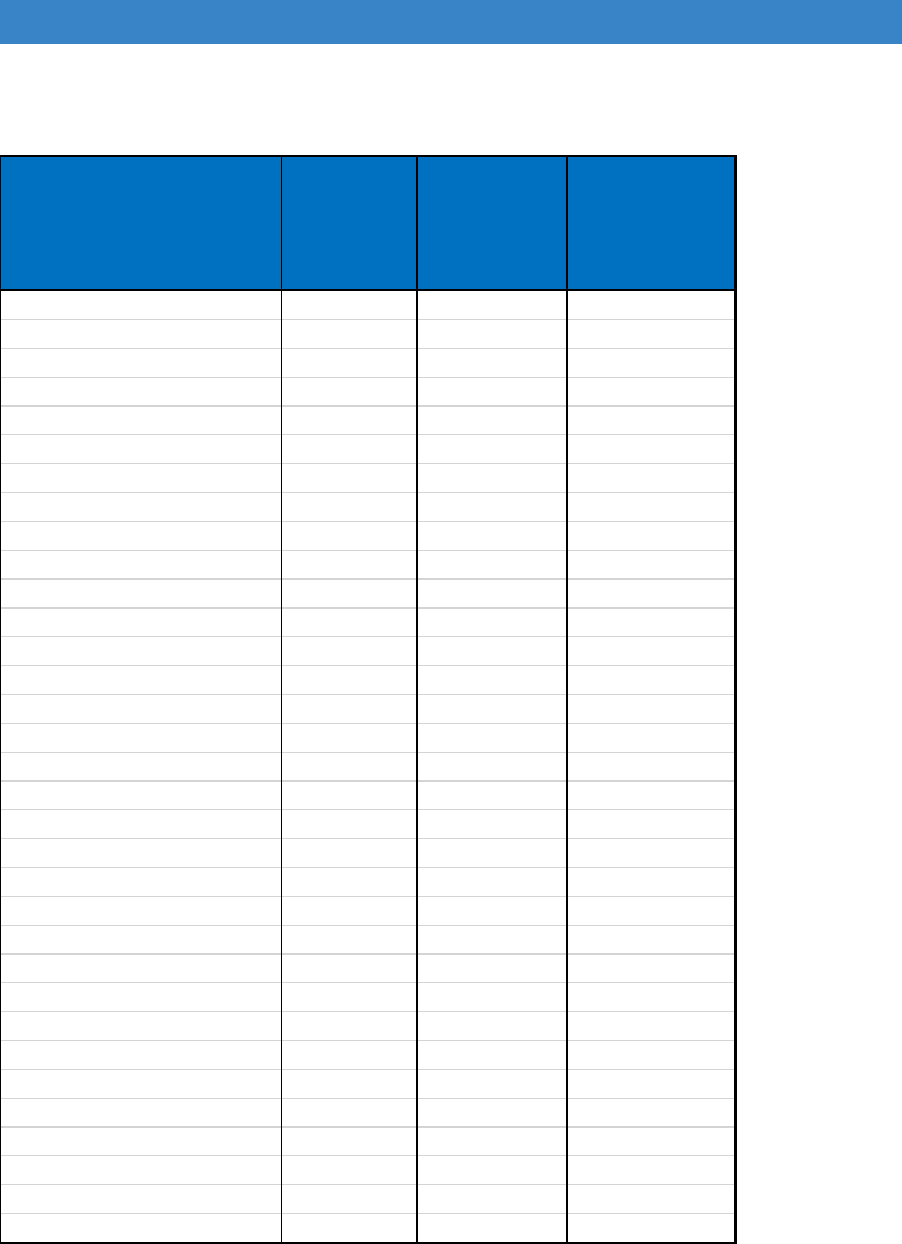

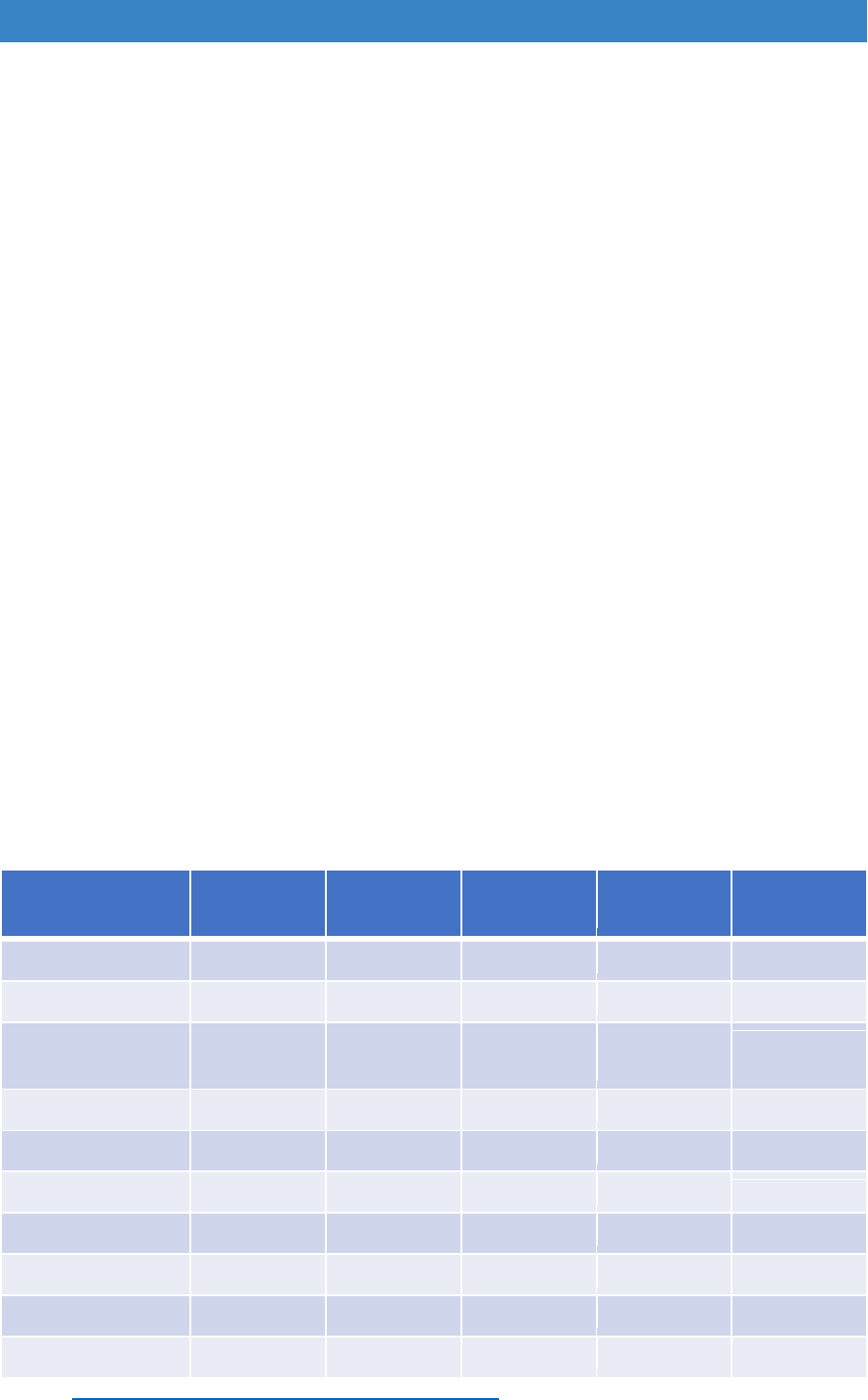

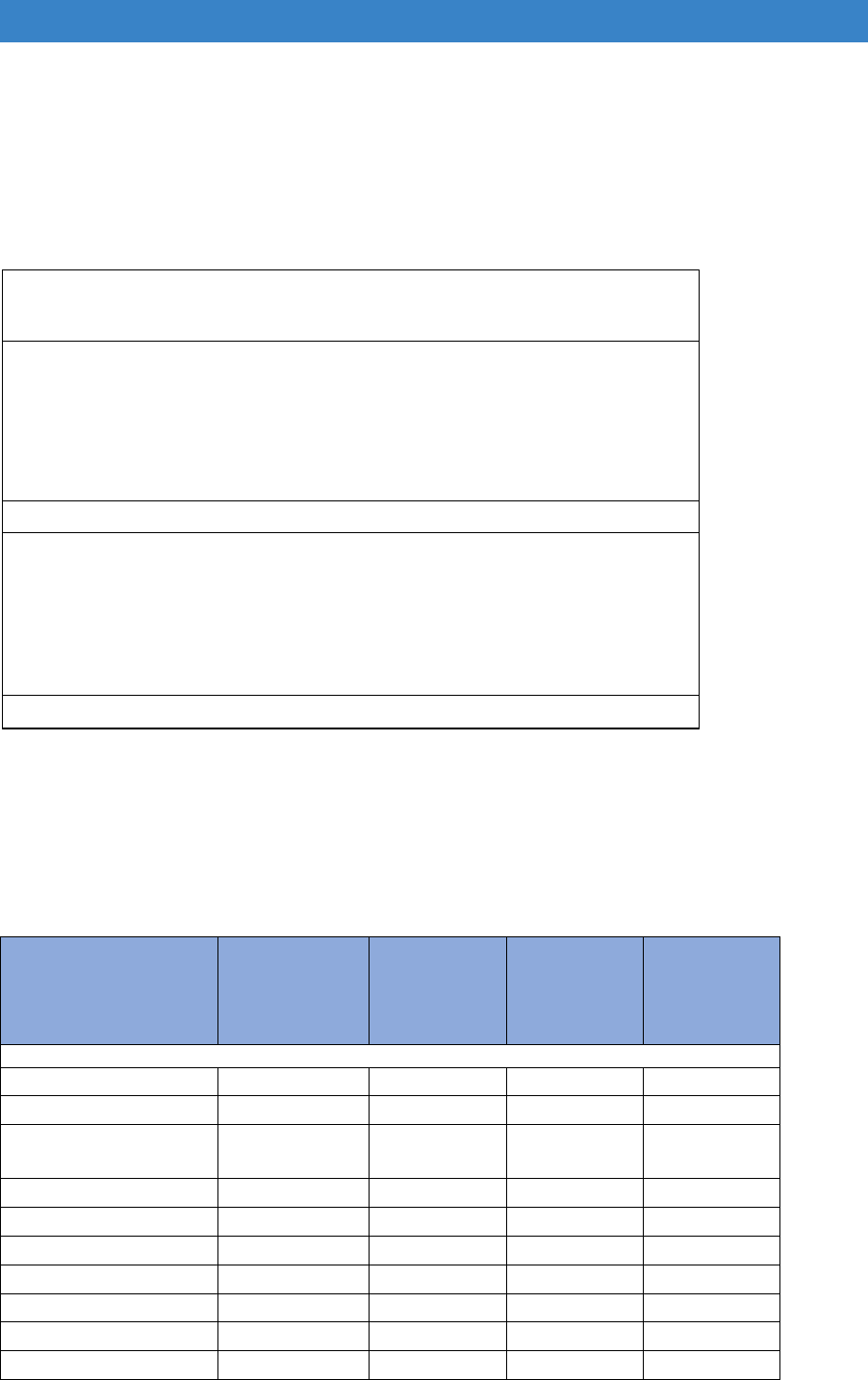

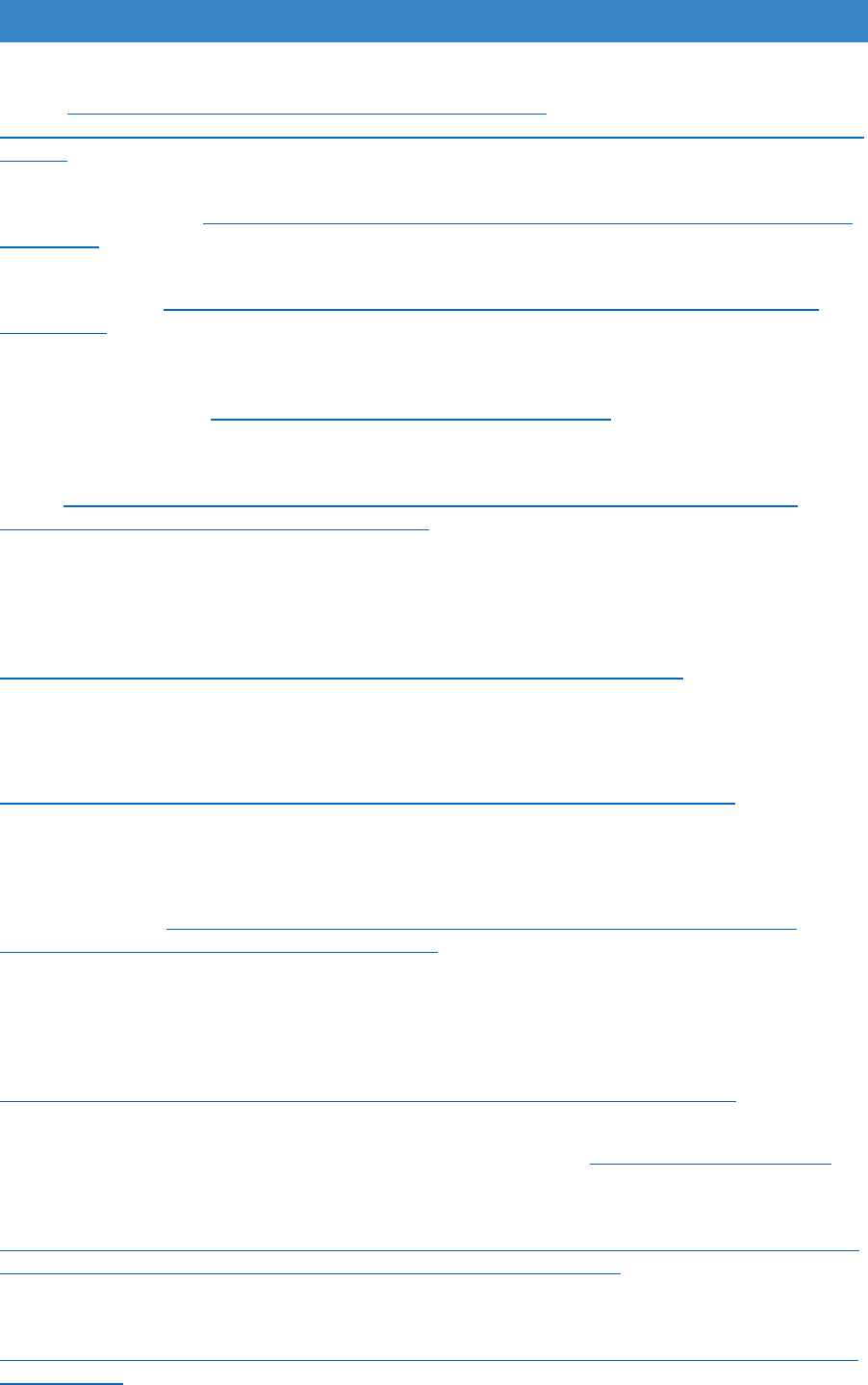

3.2 DFG funding has fluctuated over the last decade (Figure 3.1). Until 2008, local

authorities had to provide a 40% contribution to DFG budgets to match the 60%

coming from central government. The total amount was ring-fenced and had to

be spent on mandatory work as laid down in the 1996 Act. In 2008 the ring fence

was removed to give local authorities more flexibility to use the grant for

discretionary purposes. It was thought this might reduce local authority capital

contributions, but despite the greater freedom, matched contributions continued

for several years (Figure 3.1).

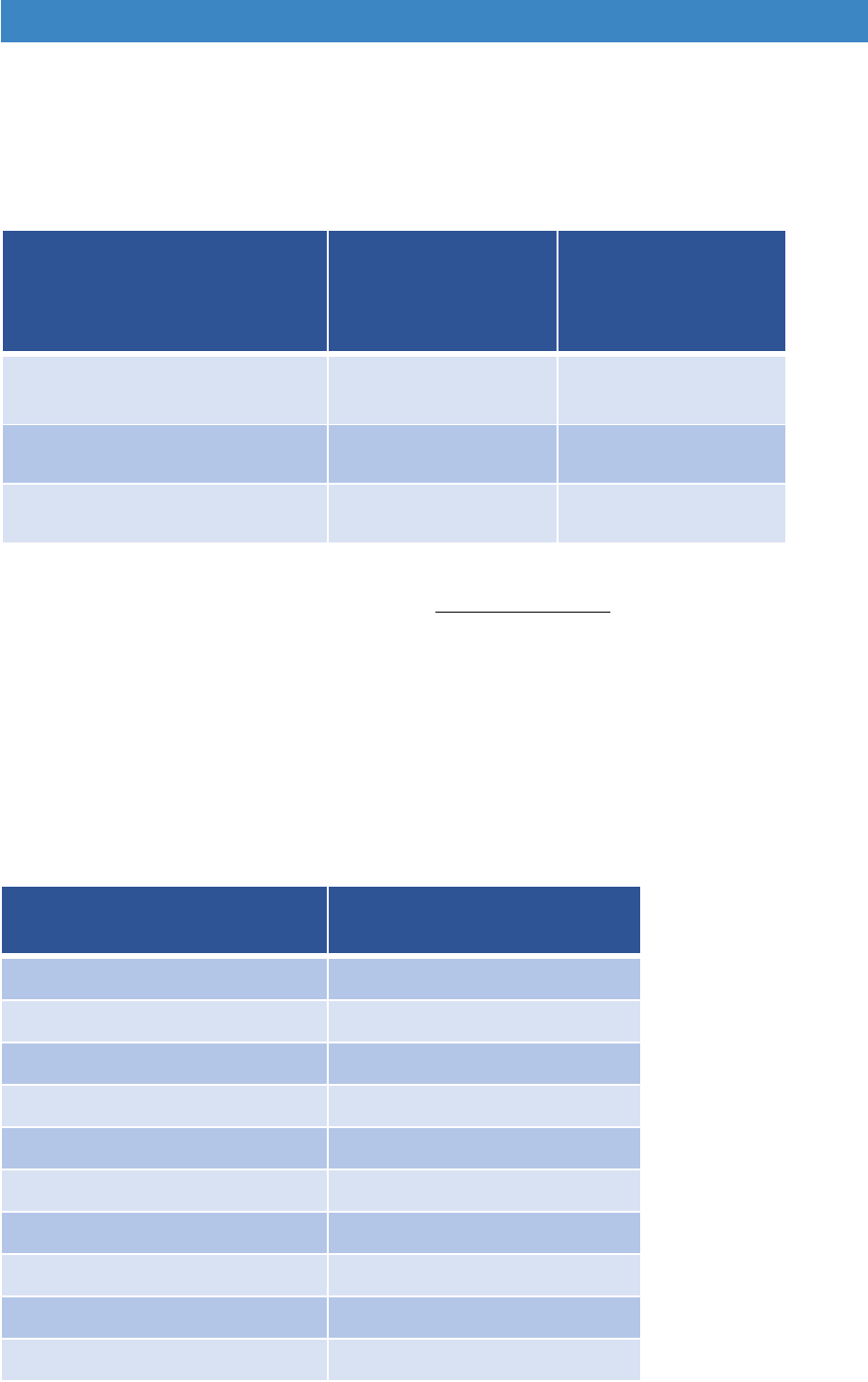

Figure 3.1 Annual DFG budget for England

?

?

Source: Annual Government allocations from official figures, LA contribution based on average

percentage contribution from LOGASNET (2009/10 – 2014/15) and Foundations FOI request (2015/16

– 2016/17).

2016/17 shows negative contribution due to top-slicing of allocation for other purposes.

Data on LA contribution not yet available for 2017/18 onwards.

9

For further details about LOGASnet see Mackintosh, S. and Leather, P. (2016) ibid.

21

Disabled Facilities Grant (DFG) and Other Adaptations: Main Report

3.3 Austerity measures were introduced in the 2010 Autumn Statement. Central

government funding for Repairs Grants ceased entirely at this point which

removed £300m of annual funding from private sector housing. This was often

used to supplement the adaptations budget, and when it disappeared local

authority contributions were cut in many areas, although the impact was not fully

felt until 2012/13. Local authority funding picked up in 2013/14 but declined to a

very low level in 2016/17 at the point when central government funding increased

significantly. The overall budget is now considerably higher than it was in

2009/10.

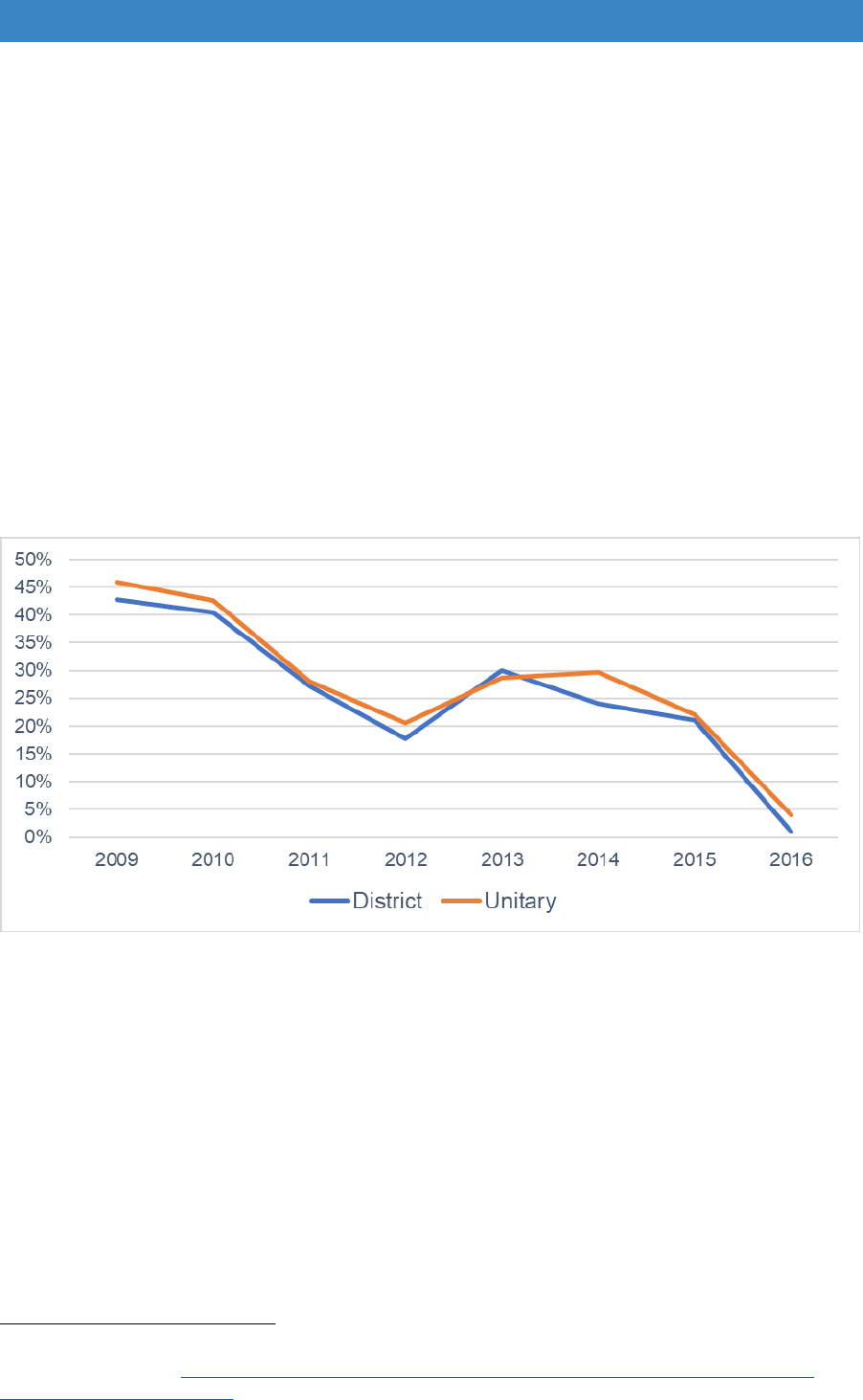

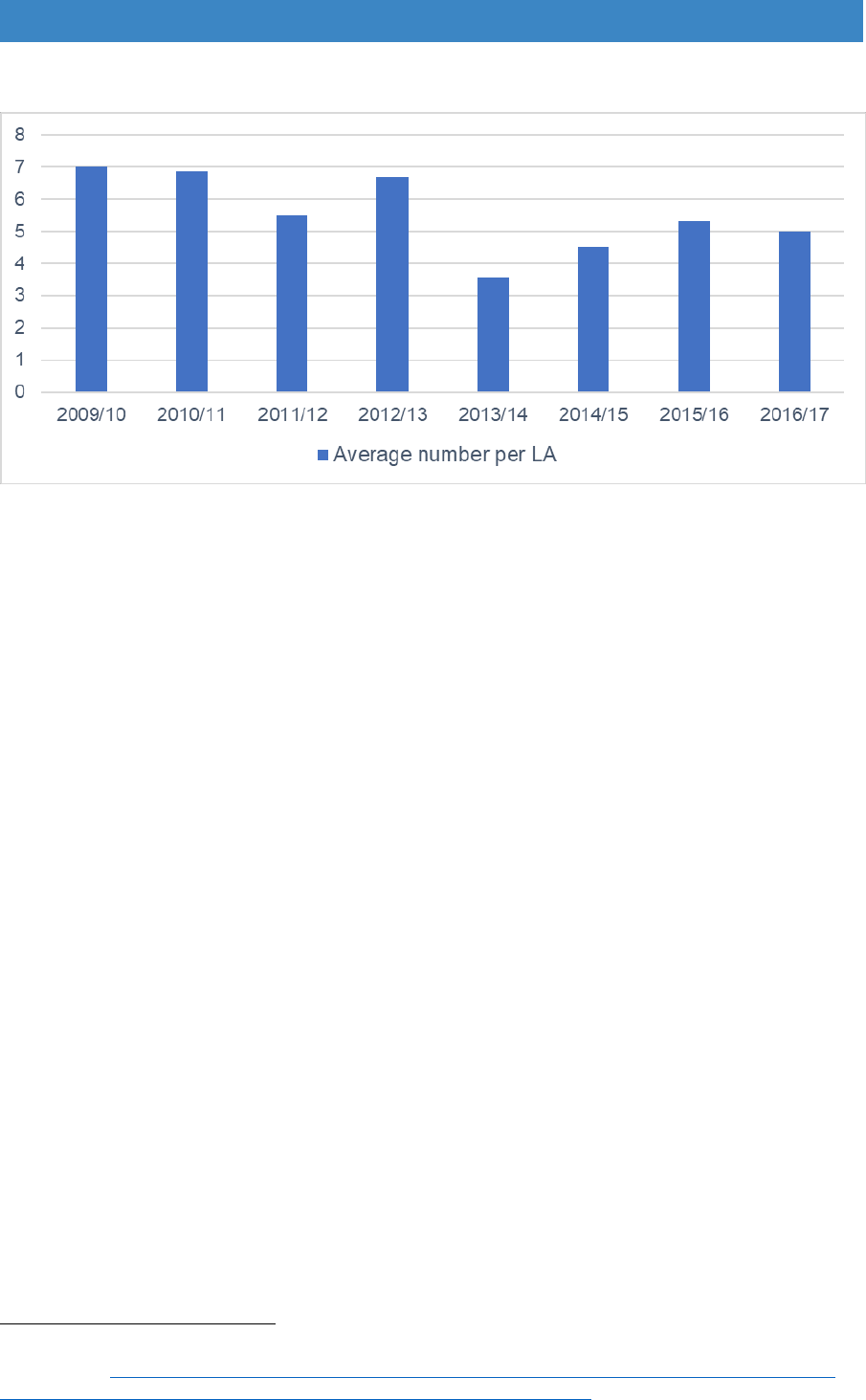

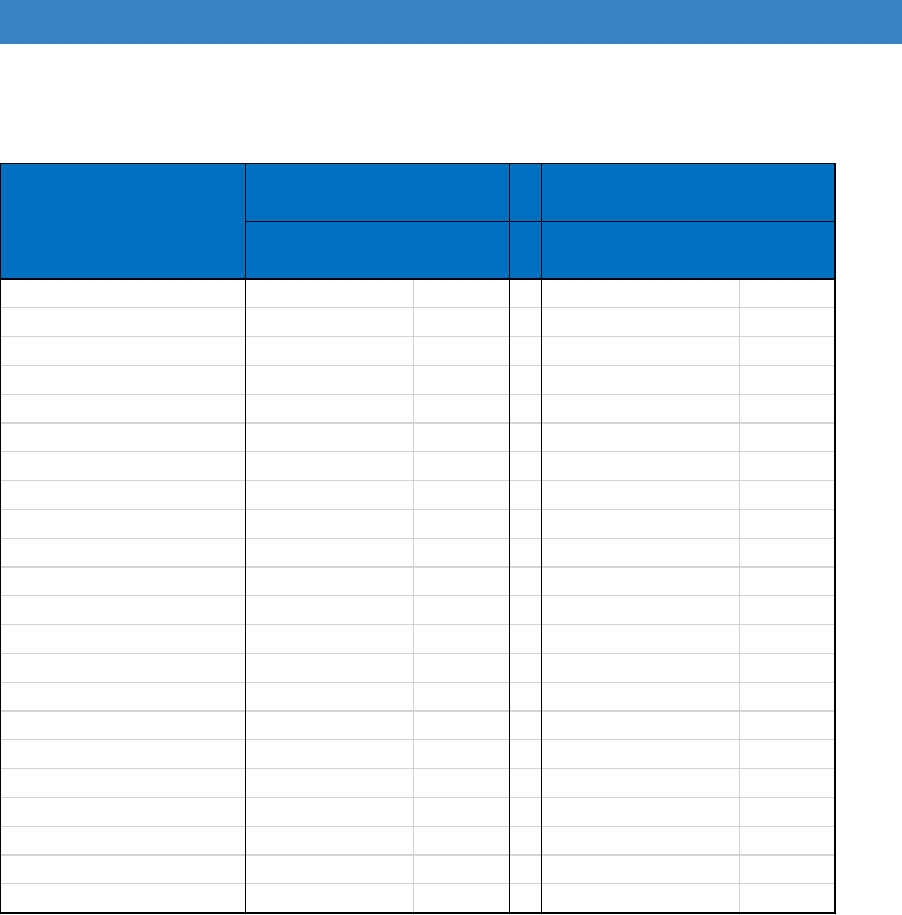

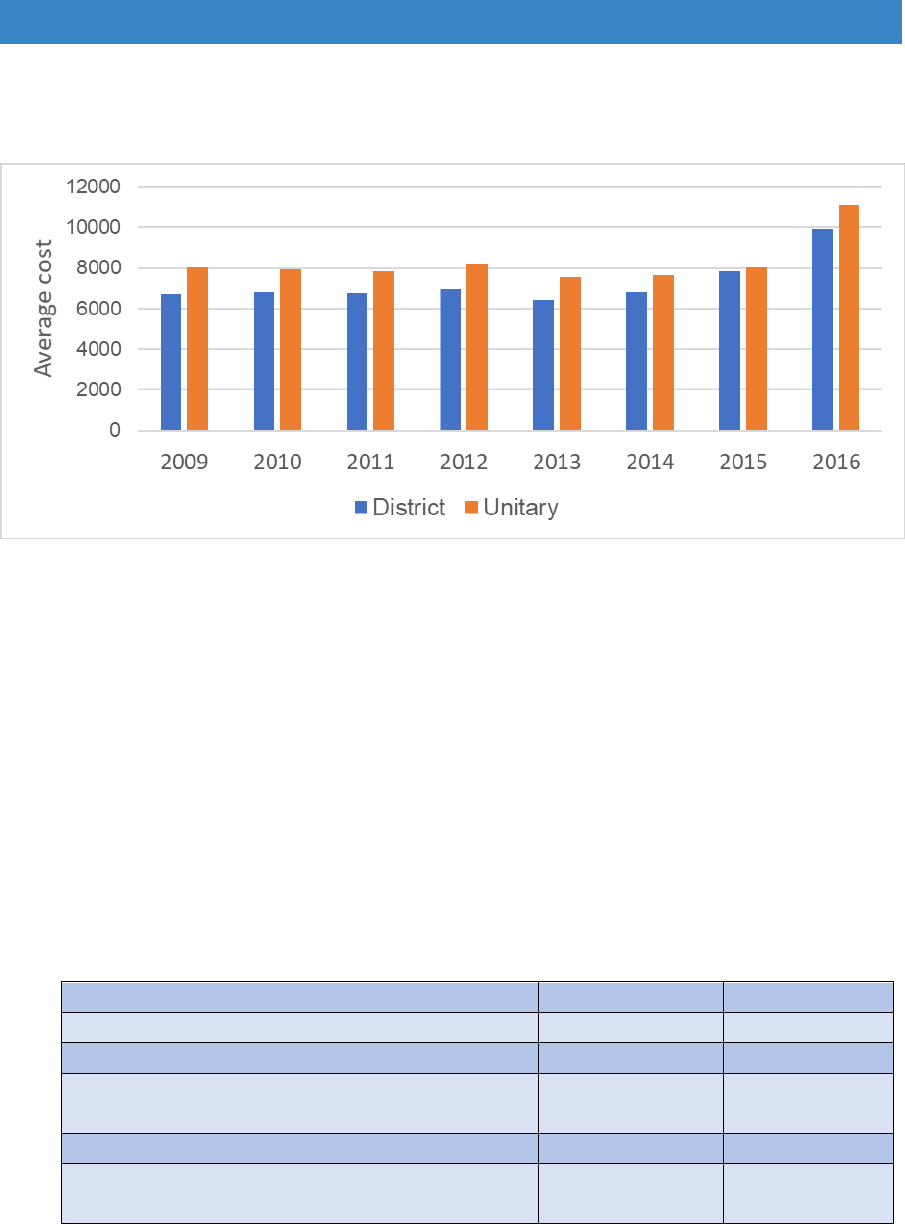

3.4 Figure 3.2 shows that local authority contributions have declined in both unitary

and two-tier authorities. They have also fallen at a similar rate in areas with

retained council stock, compared to those where the stock has been transferred.

Figure 3.2 Average local authority contributions 2009-2016.

Source: LOGASnet and Foundations FOI requests

3.5 In the 2015 Spending Review, it was announced that central government

contributions to the DFG would increase until the end of the decade to help meet

the objectives of the 2014 Care Act and the Better Care Fund.

“The Care Act reforms introduced in April focus on wellbeing, prevention

and delaying the need for social care. In support of these principles, the

Spending Review includes over £500 million by 2019-20 for the Disabled

Facilities Grant, which will fund around 85,000 home adaptations that

year. This is expected to prevent 8,500 people from needing to go into

a care home in 2019-20”

10

.

10

HM Treasury (Nov 2015) Spending Review and Autumn Statement 2015, Adult Social Care,

Section 1.109, p. 33. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/spending-review-and-autumn-

statement-2015-documents.

22

Disabled Facilities Grant (DFG) and Other Adaptations: Main Report

3.6 It was clearly hoped that local authorities would continue to add resources and

that the number of grants delivered would more than double from the 41,000

completed in 2014/15. With the decline in local authority contributions, overall

DFG funding levels only rose 44% from 2015/16 to 2016/17, and a further 13%

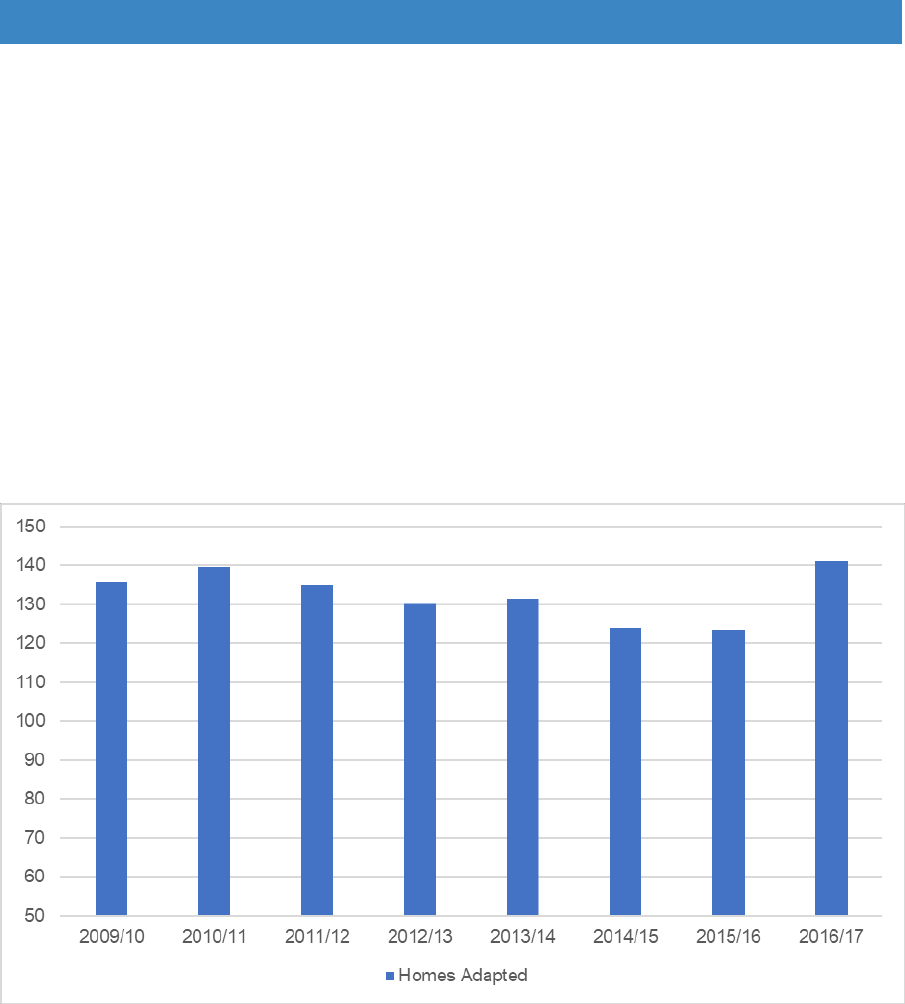

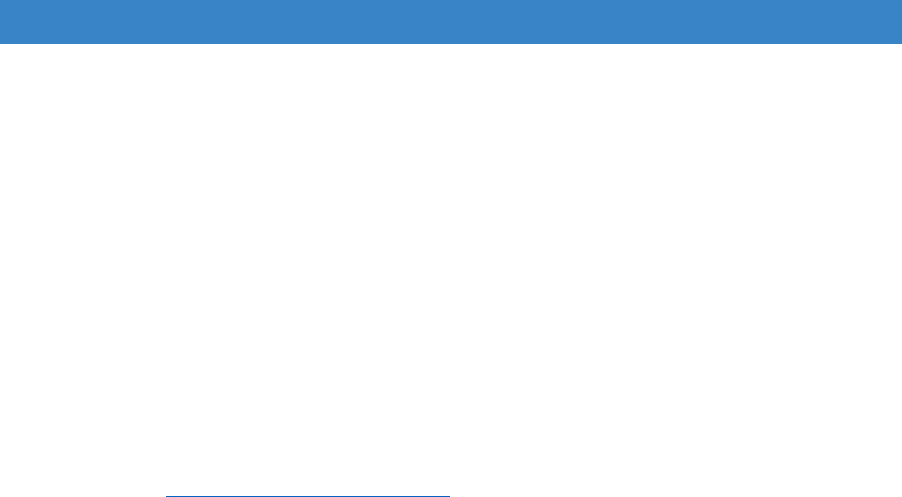

to 2017/18 (Figure 3.1). Grant completions have taken longer to respond. The

average number of grants per authority declined after 2010/11. Completions only

increased after 2015/16 when they rose from an average of 123 to 141 per

authority in 2016/17; a rise of only 15%. This takes the levels of completions back

to the amount achieved in 2010/11, before austerity measures were introduced

(Figure 3.3). In 2010/11, about 45,500 grants were completed nationally, and we

estimate it was only 46,000 in 2016/17.

Figure 3.3 Average number of DFGs completed per authority 2009/10-2016/17

Source: LOGASnet – includes both mandatory and discretionary grants for 2016/17

Reasons behind the trends

3.7 The reasons why numbers of DFG completions are not increasing as fast as

expected are complex and may include the following:

a) Time lag – in the first year that funding increases, the number of grant

approvals may rise. However, due to the time it takes to schedule building

work the number of grant completions may not show in the figures until the

following year. The figures for 2017/18 are not yet available to show the true

impact of the increase in central government funding.

23

Disabled Facilities Grant (DFG) and Other Adaptations: Main Report

b) Delays in obtaining DFG allocations - DFG resources used to be passed

directly from central government to the housing authorities based in unitary

authorities and at borough or district level. Now the grant is part of the BCF,

in shire authorities it goes to the county before being passed to the boroughs

or districts.

In 2016/17, there was a small negative contribution when 22% of authorities

saw their budgets top sliced for other purposes, mainly to meet social care

obligations under another funding stream that was discontinued. Other

authorities may have received their allocation quite late in the year. The

guidance issued in a letter to all authorities and in the BCF planning

requirements for 2017-19 states clearly that the statutory duty on local

housing authorities to provide the DFG to those who qualify for it remains

11

.

“DFG funding allocated by central government should be

passed down by the county to the districts (in full, unless

jointly agreed to do otherwise) to enable them to continue

to meet their statutory duty to provide adaptations.”

12

Although top slicing may have impacted grant completion levels in 2016/17

(the most recent LOGASnet data currently available), it appears to have

affected few authorities in 2017/18.

c) More discretionary grants - discretionary grants include: fast-tracked grants

for hospital discharge; grants for people with dementia; funding to improve

heating; and a range of other measures to ensure that people can remain

safely at home. Many are given without a means test to ensure that they can

be delivered quickly. These grants are only just being introduced in most

areas and may not be reflected in the figures until 2017/18. LOGASnet returns

in 2016/17 included totals of discretionary grants for the first time (they are

included in the data in Figure 3.1 above). However, three quarters of

authorities did none, 17% did less than 10 and only 5% of local authorities did

more than 50 in 2016/17 (Foundations FOI 2017). It is hoped that more of

these flexible grants will be shown in the data for 2017/18.

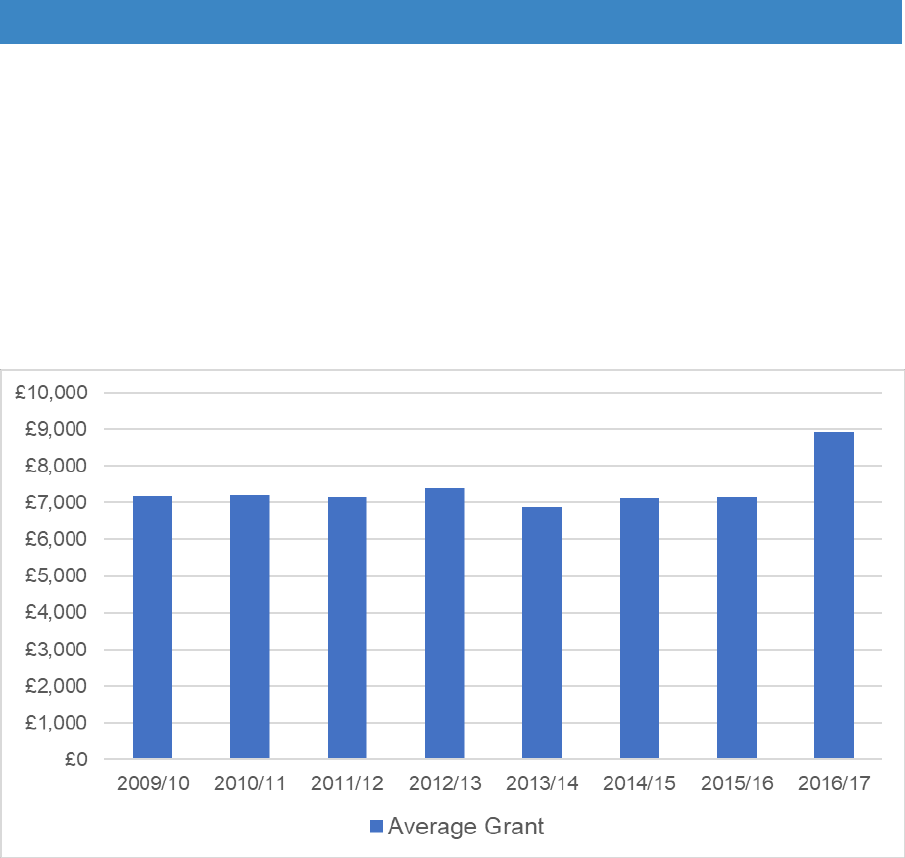

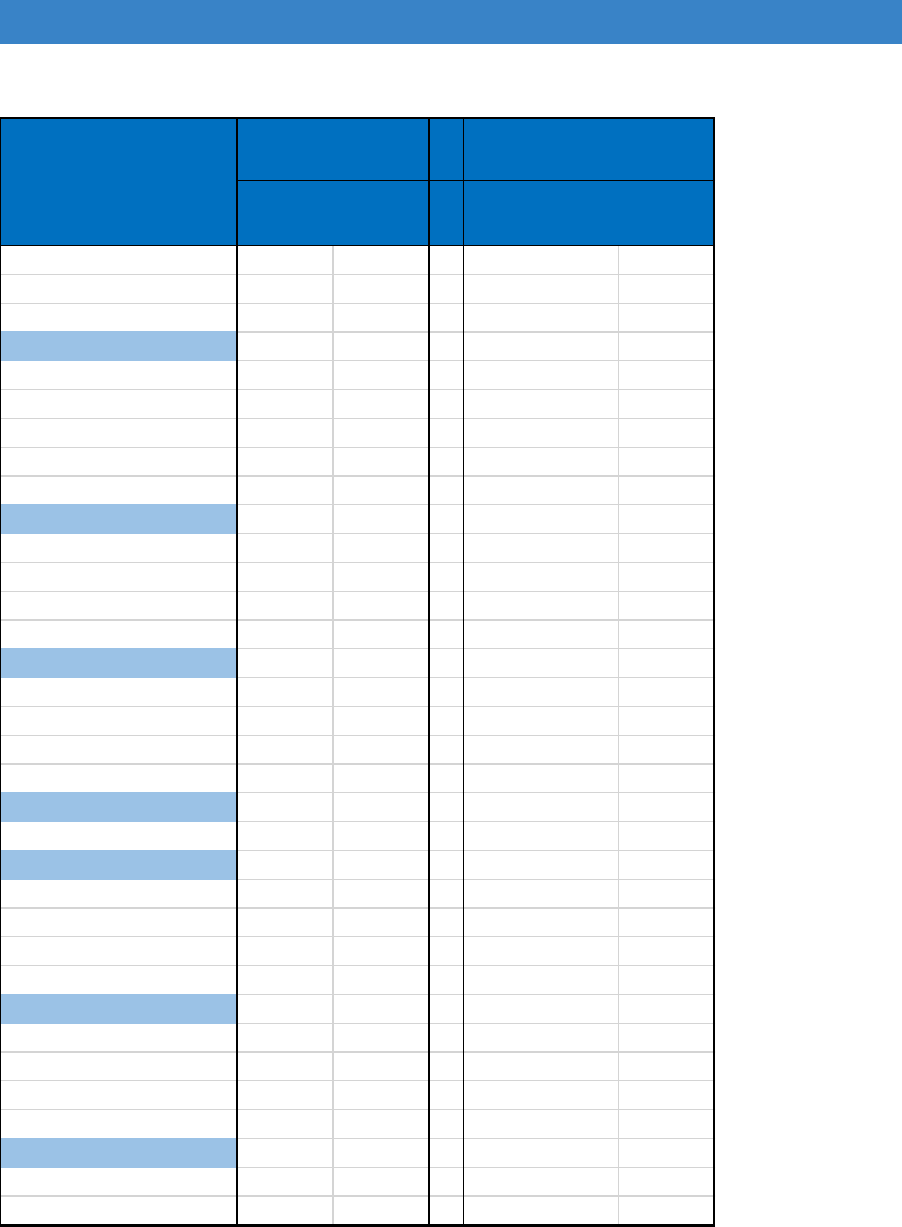

d) Rising cost of work – until central government contributions increased after

2015, local authorities were struggling with restricted DFG resources relative

to demand. Therefore, there was a focus on value for money and on driving

down costs. As a result, the average remained constant for many years,

despite rising building costs (Figure 3.4).

11

NHS England (2017) Integration and Better Care Fund planning requirements for 2017-19.

https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/integration-better-care-fund-planning-

requirements.pdf.

12

NHS England (Aug 2017) The Better Care Fund Planning Requirements 2017-19: Frequently

Asked Questions, p. 9. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/bcf-planning-

requirements-faqs.pdf.

24

Disabled Facilities Grant (DFG) and Other Adaptations: Main Report

In 2016/17 average costs rose from around £7,000 over the period 2009/10-

2015/16 to nearly £9,000 in 2016/17, showing that the overall increase in

resources has allowed prices to rise, perhaps to more realistic levels (Figure

3.4). Cost rises may also reflect the increased complexity of cases which is

discussed later in the report. Minimal specifications may not provide the best

solutions, and a relaxing of very tight cost controls may be beneficial, but it

has the effect of reducing the overall number of grants delivered.

Figure 3.4 Trends in average grant value 2009/10 to 2016/17

Source: LOGASnet

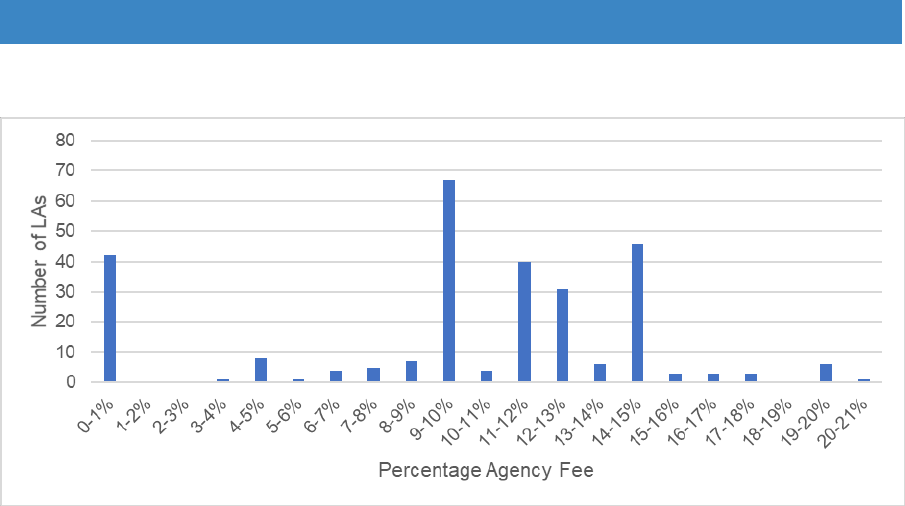

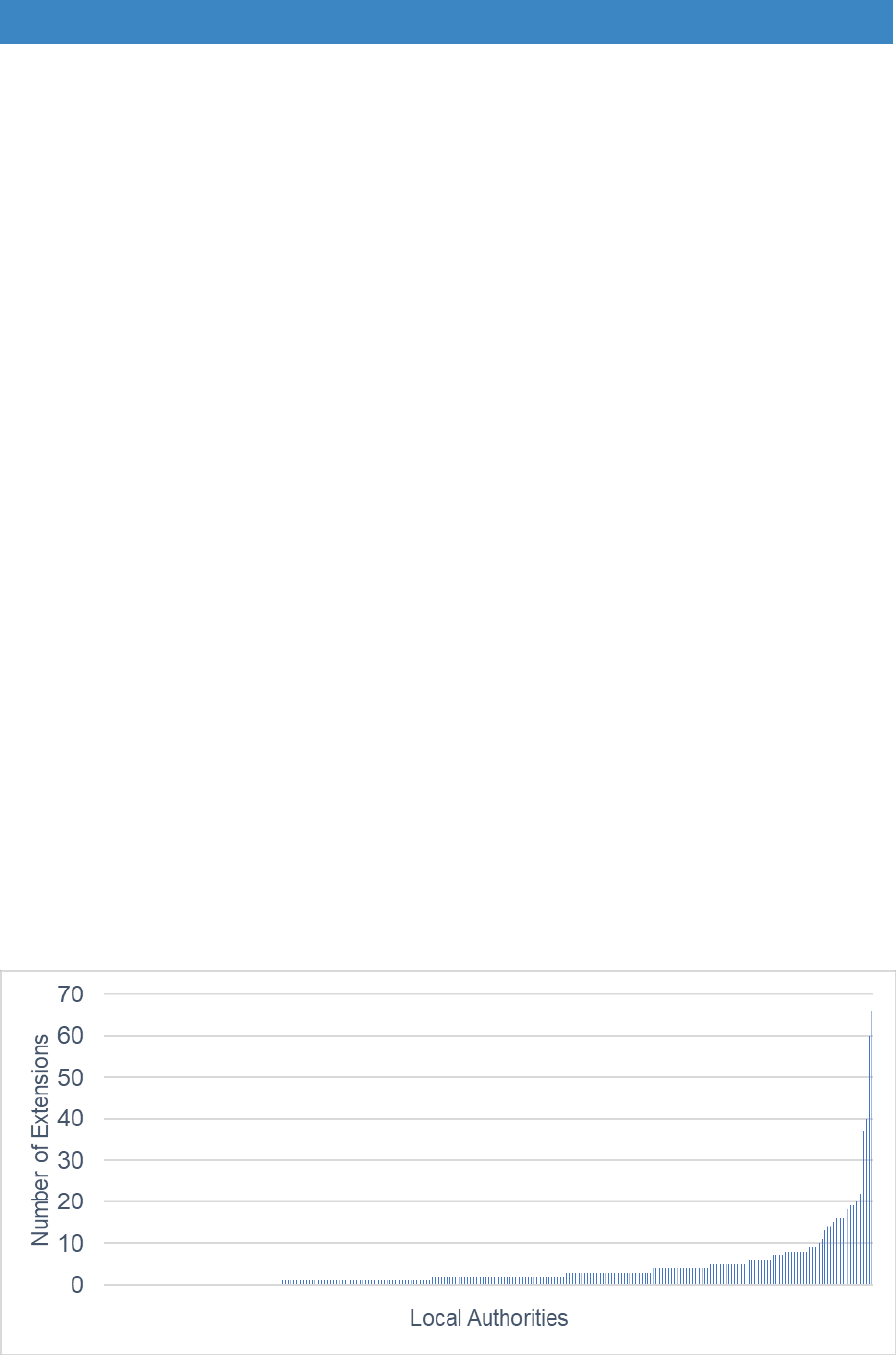

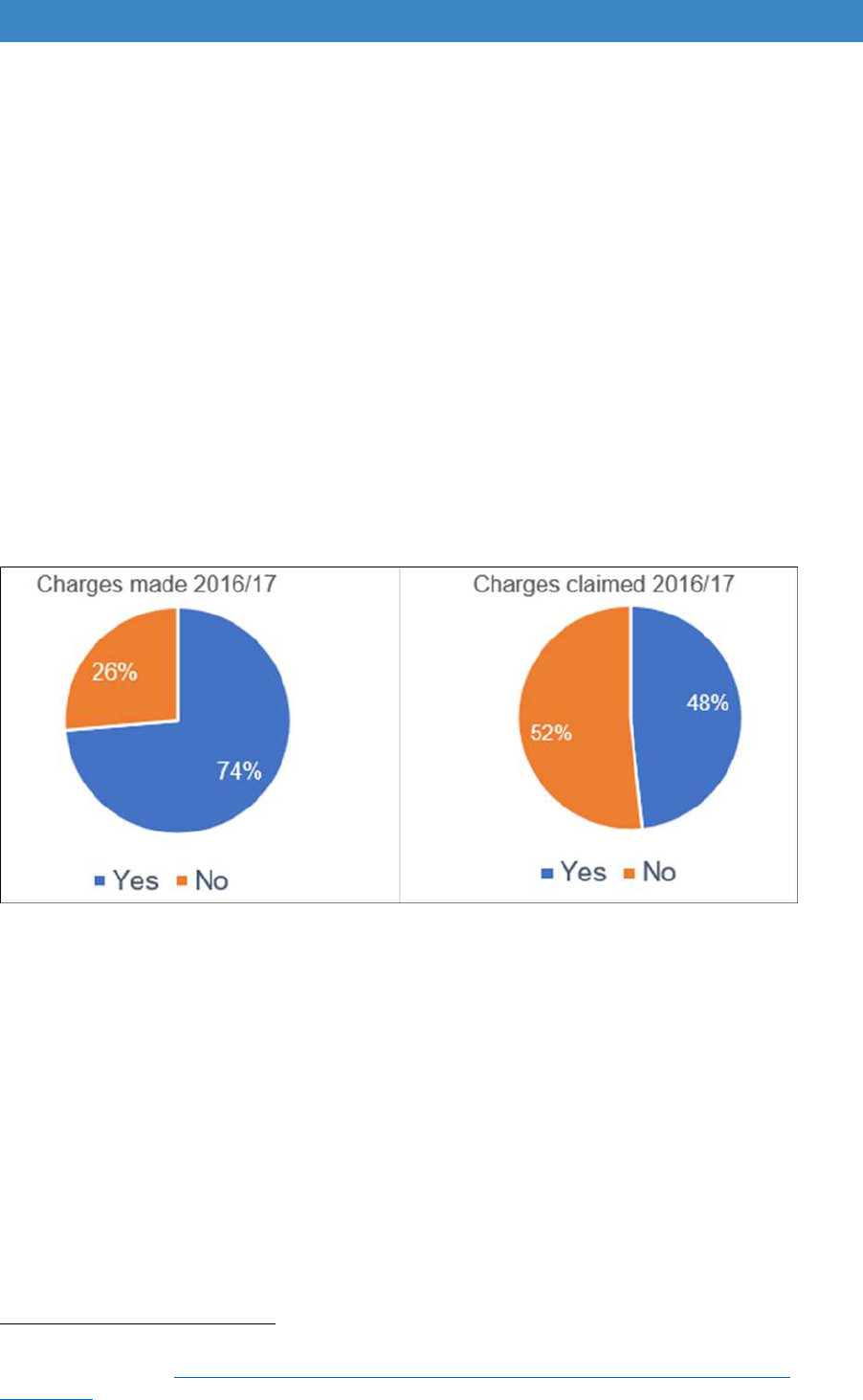

e) Problems with revenue funding – the increase in DFG capital allocations

happened at a time when local authorities were continuing to cut staff to

reduce costs. This may have impacted on their ability to deliver more

adaptations in 2016/17. To maintain staffing levels, some authorities began

to look at other ways of finding revenue funding. As a result, more started to

charge fees of 10-15% on top of each DFG grant to cover running costs

(these fees are not charged on to DFG recipients). A few other authorities

top-sliced the budget to cover service costs. This may have further reduced

grant completion numbers (Figure 3.5).

25

Disabled Facilities Grant (DFG) and Other Adaptations: Main Report

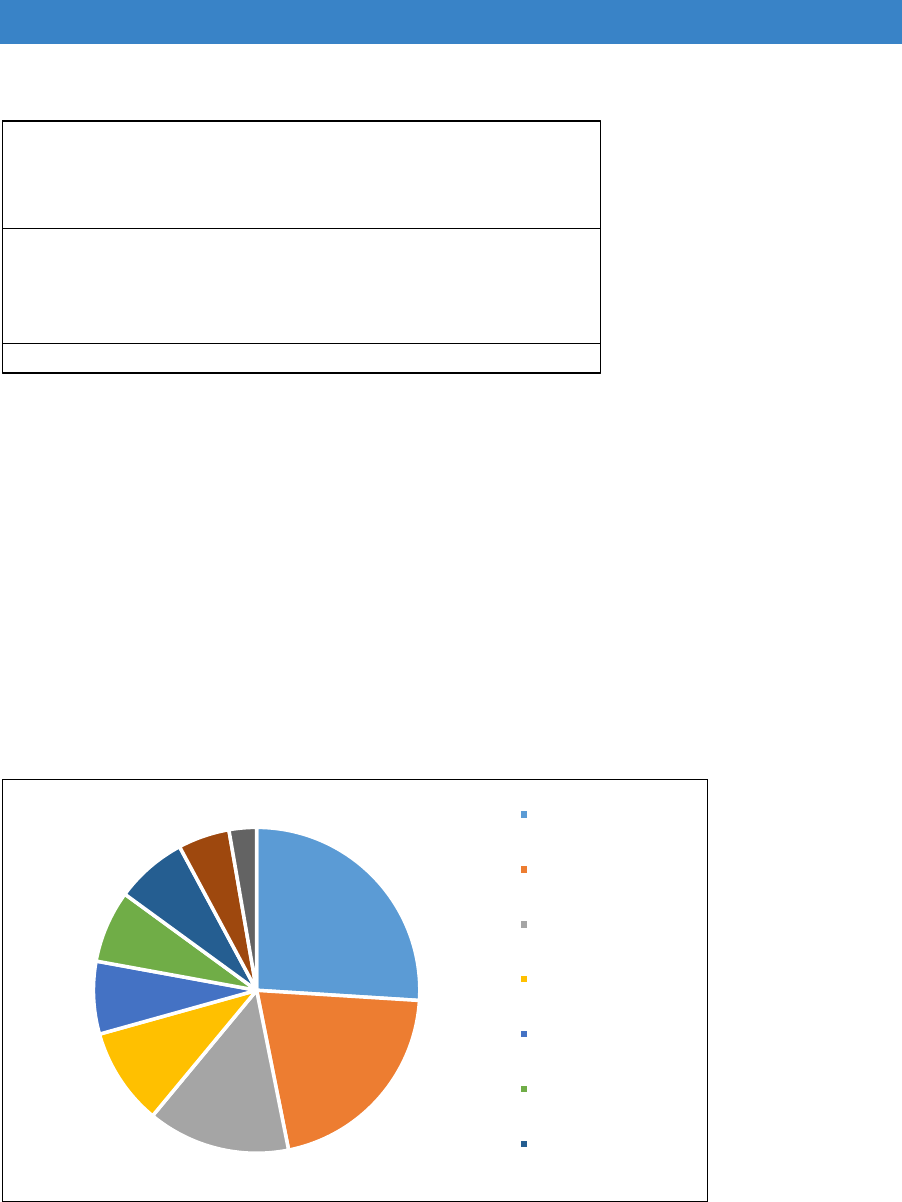

Figure 3.5 The range of agency fees charged as part of the DFG in 2016/17

Source: Foundations FOI 2017

The need to increase the number of grants

3.8 Given the pressures on health and social care and the rising numbers of people

living with impairments or long-term conditions, it is essential to enable more

people to remain independent in their homes. There is an urgent need to work

towards the target of 85,000 grants per year, which was set when central

government funding increased in 2015. How revenue funding could be increased

and DFG funding used to help more people is discussed further in Section B.

Summary - funding issues

There are several reasons why numbers of grants have not increased as much as

expected by 2016/17. These include: reduction in local authority contributions;

delays in funding being passed to authorities; lack of detail about use of

discretionary grants; a rise in the complexity of work; and the relaxation of strict

cost controls resulting in an increase in the average cost of work.

Austerity has affected the ability of local authorities to add their own investment,

both in terms of grant spending and revenue costs. Using the grant to provide fees

to cover staff and overhead costs has further reduced outputs.

It will not be until the LOGASnet figures for 2017/18 are available that the full

benefits of increased central government spending will become apparent.

26

Disabled Facilities Grant (DFG) and Other Adaptations: Main Report

Chapter 4. Who receives the grant

4.1 The DFG is designed to help people of all ages and with a range of impairments.

A person is deemed disabled if: their sight, hearing or speech is substantially

impaired; they have a mental disorder or impairment of any kind or they are

physically substantially disabled by illness, injury, or an impairment present since

birth.

4.2 The grant provides adaptations to allow access to the home and garden, permit

use of all the normal facilities and, where appropriate to enable a disabled person

to provide care for others. It also allows for a care plan to be implemented to

enable the disabled occupant to remain living in their existing home as

independently as possible

13

.

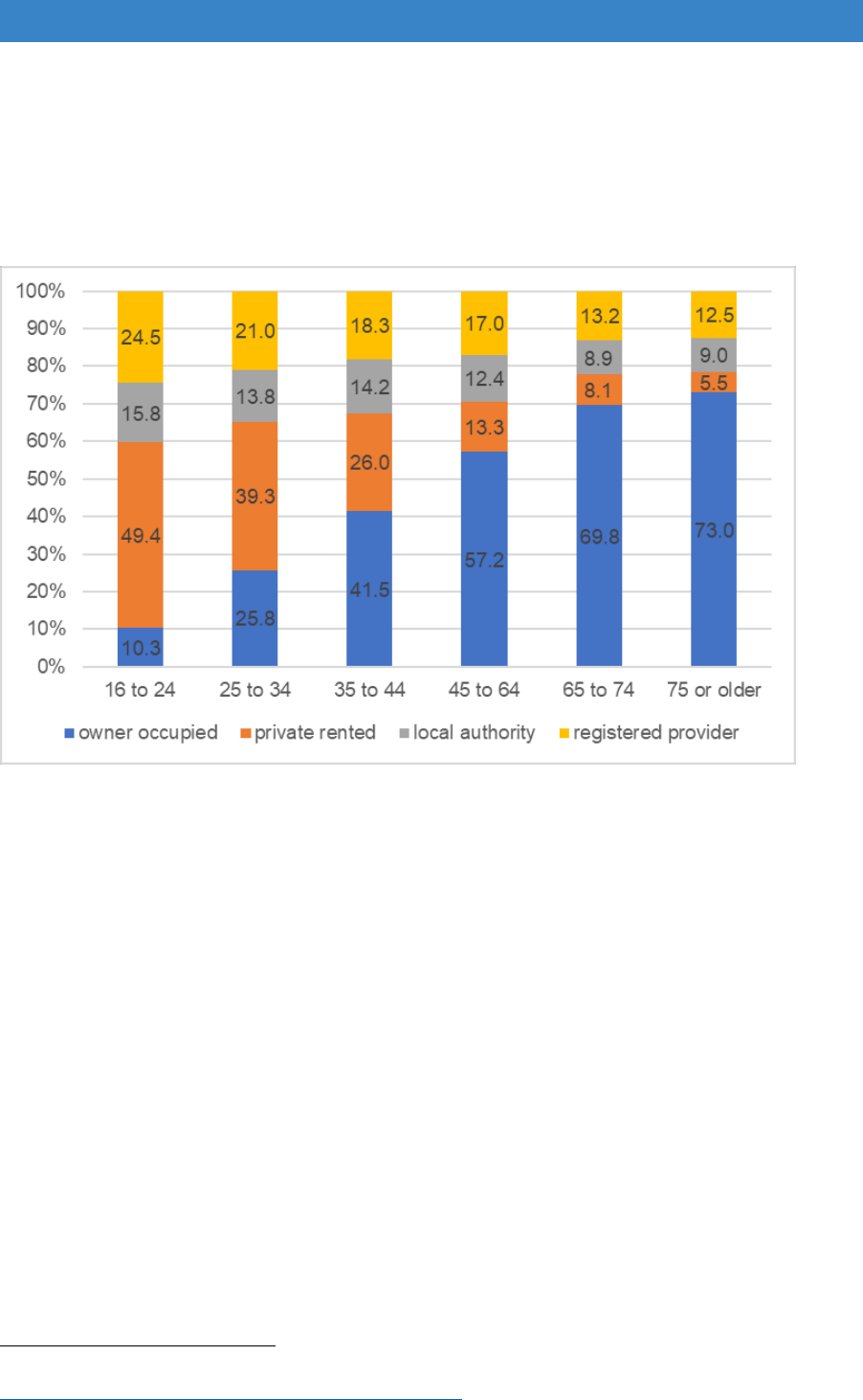

Age of DFG recipients

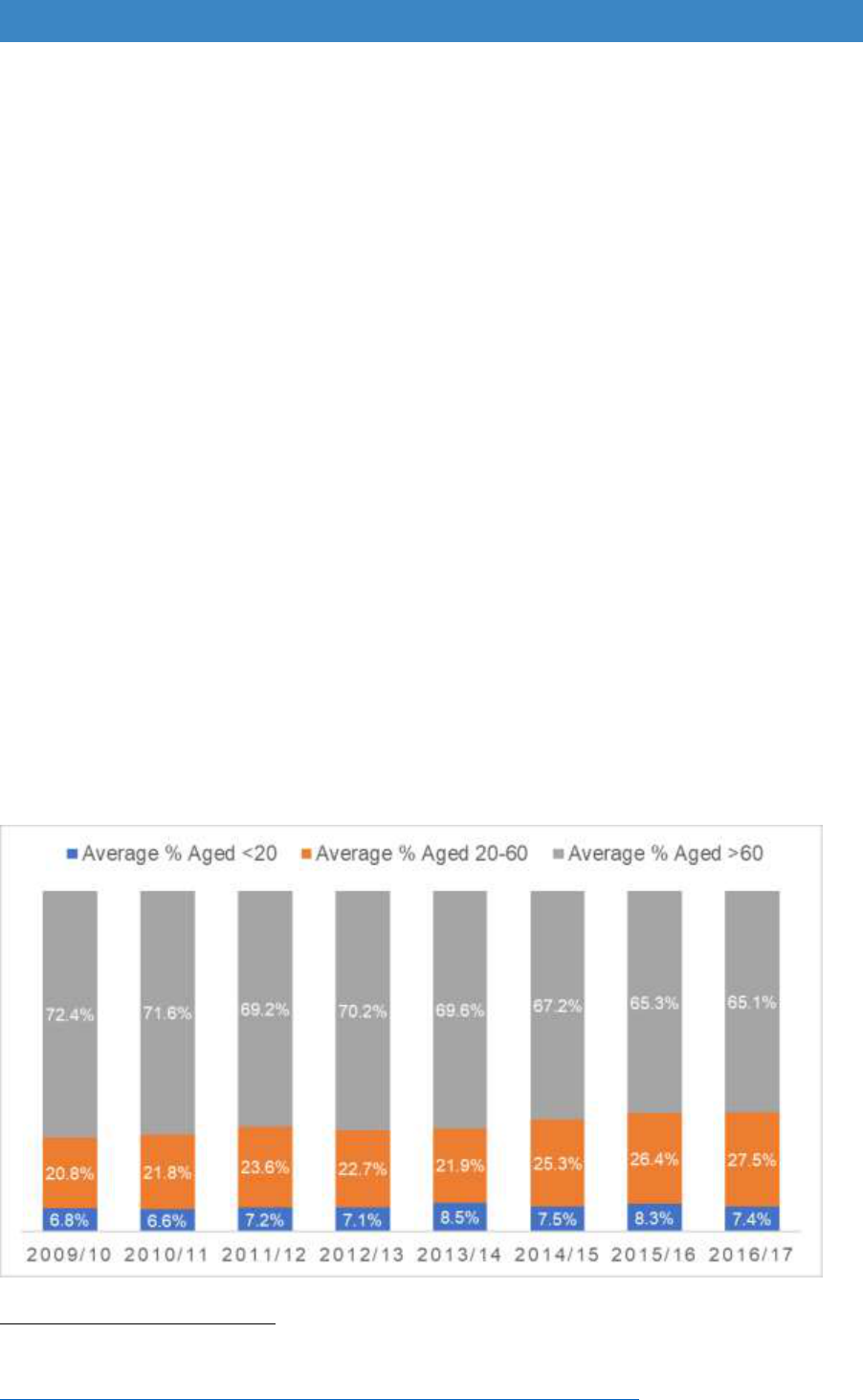

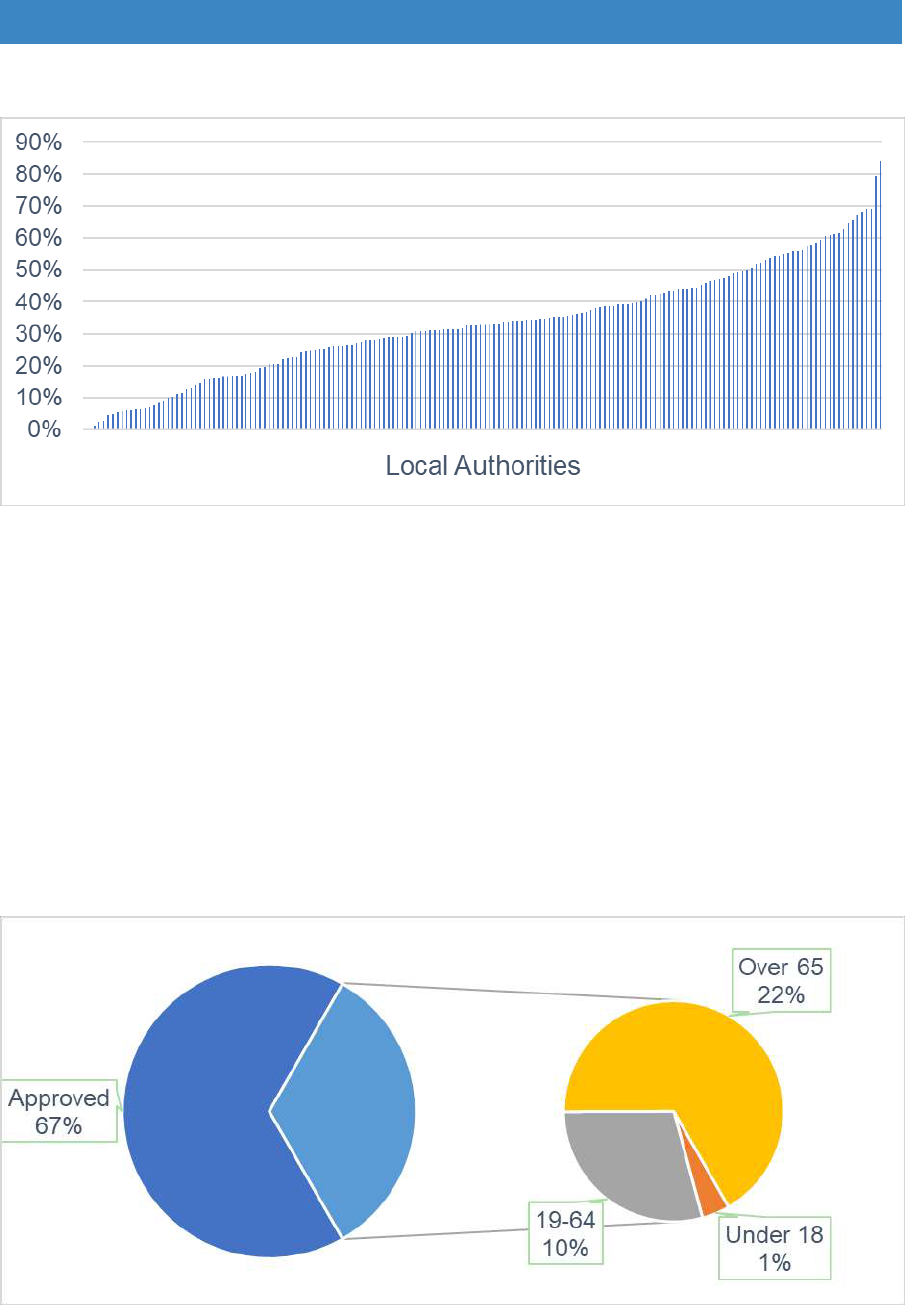

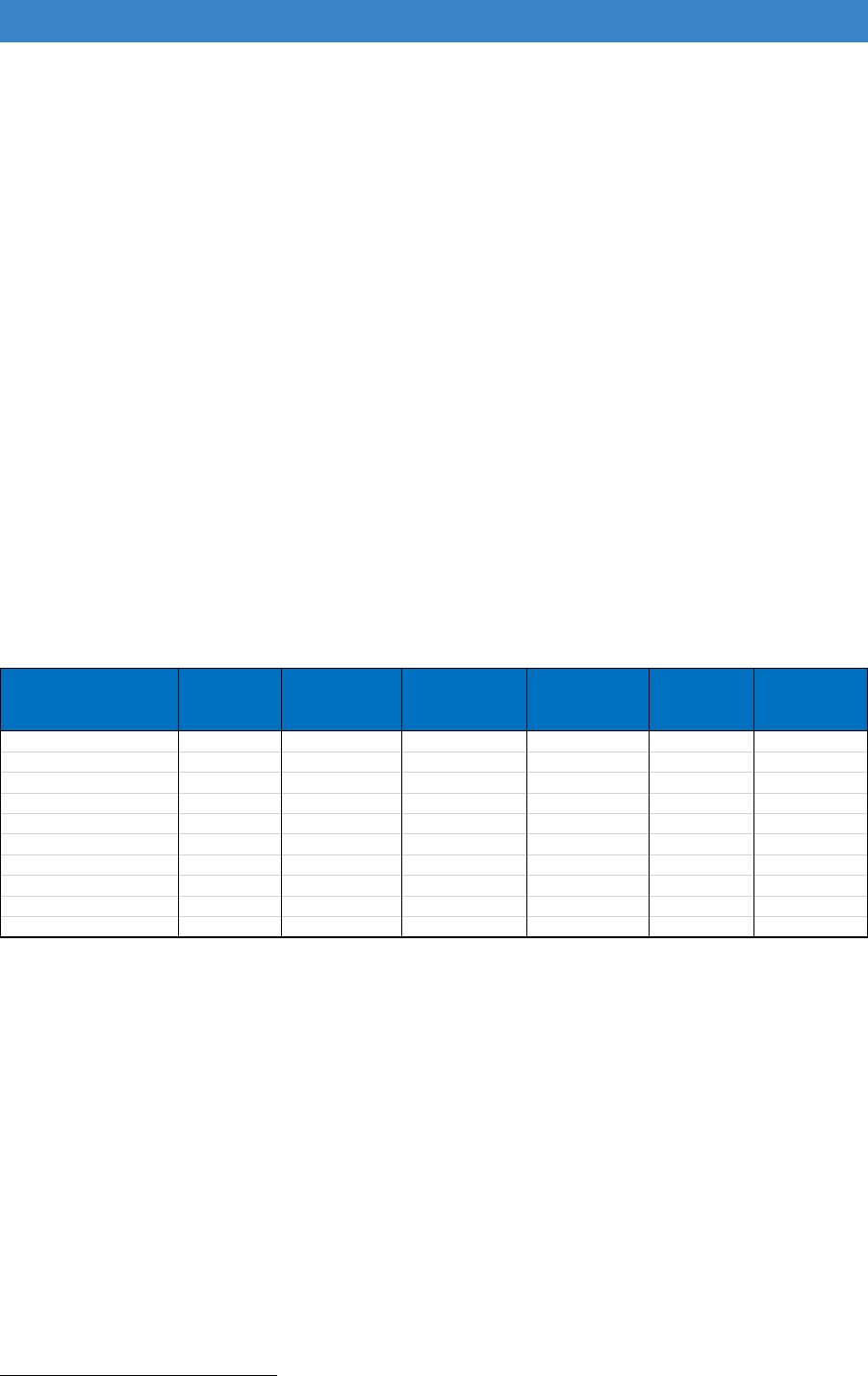

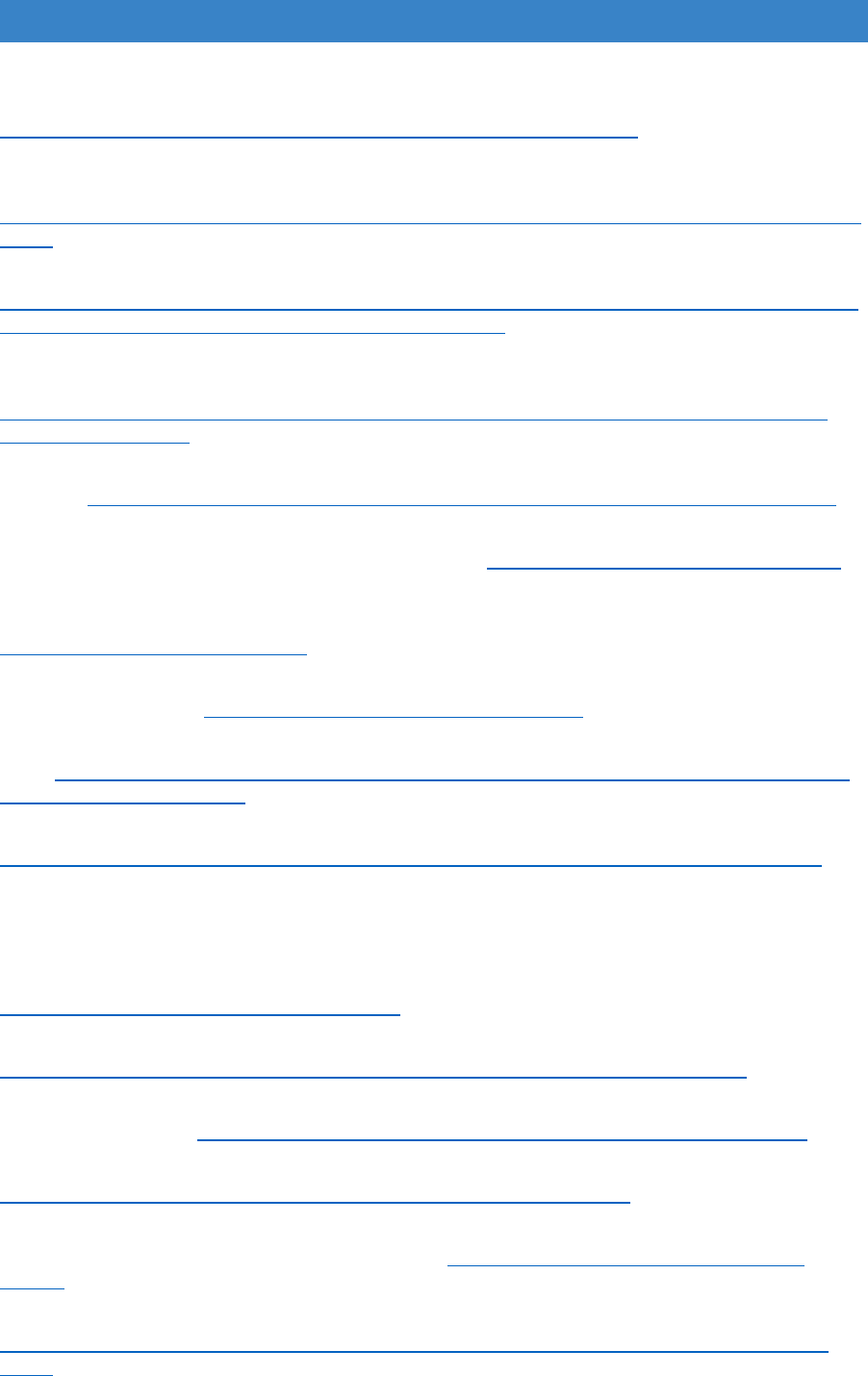

4.3 In 2016/17 most grants (65%) went to people aged 60 and over. The proportion

has gradually decreased since 2009/10, with slightly more grants going to people

of working age and to children and young people under 20 (Figure 4.1). However,

the number of grants going to people under 20 is still relatively small and

fluctuates slightly from year to year.

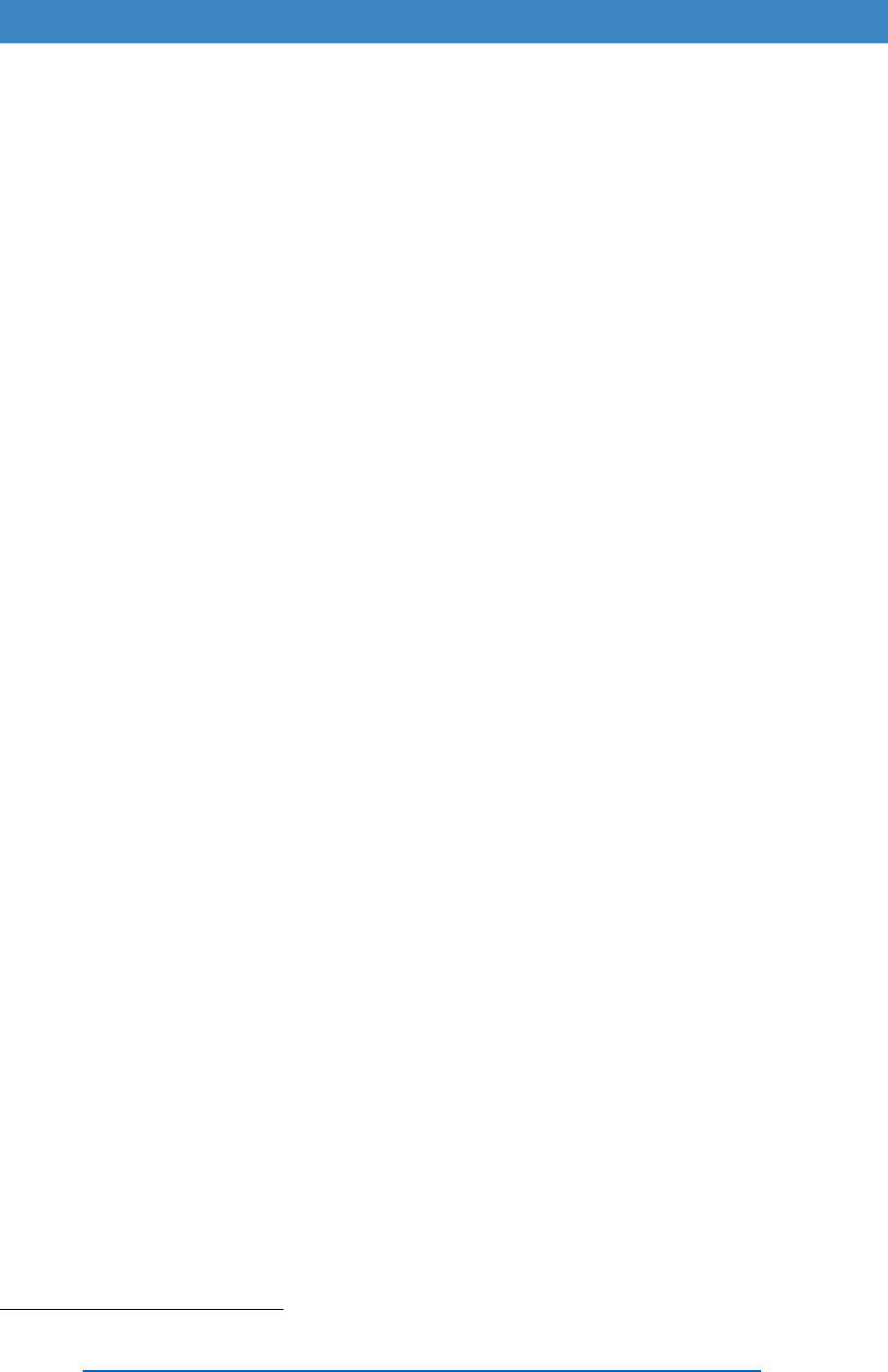

Figure 4.1 Trends in age of people receiving the DFG

Source: LOGASnet

13

Wilson, W. and Fears, C. (Dec 2016) Disabled Facilities Grants for home adaptation, Briefing Paper

No. 03011, London: House of Commons Library.

http://researchbriefings.parliament.uk/ResearchBriefing/Summary/SN03011.

27

Disabled Facilities Grant (DFG) and Other Adaptations: Main Report

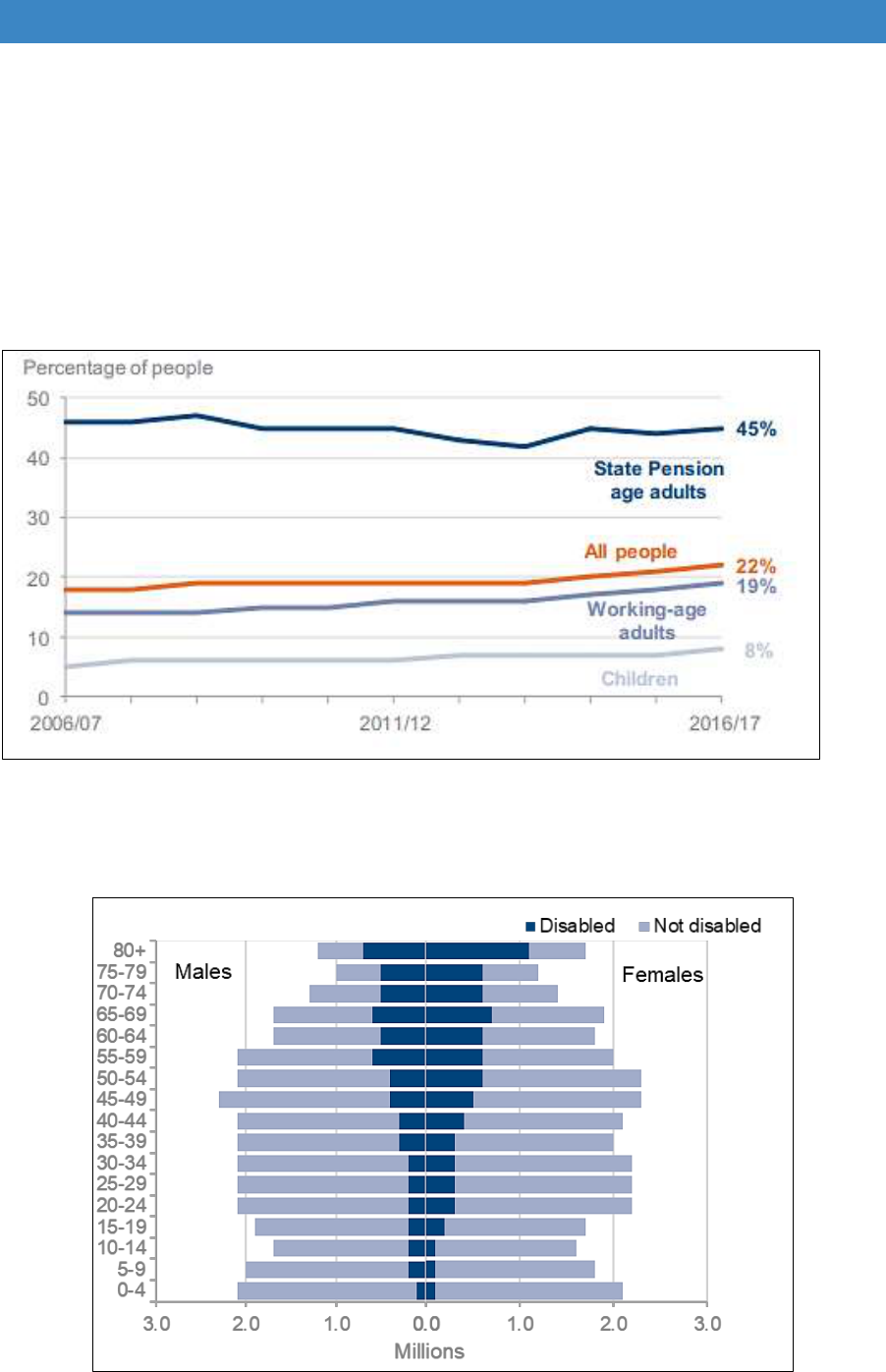

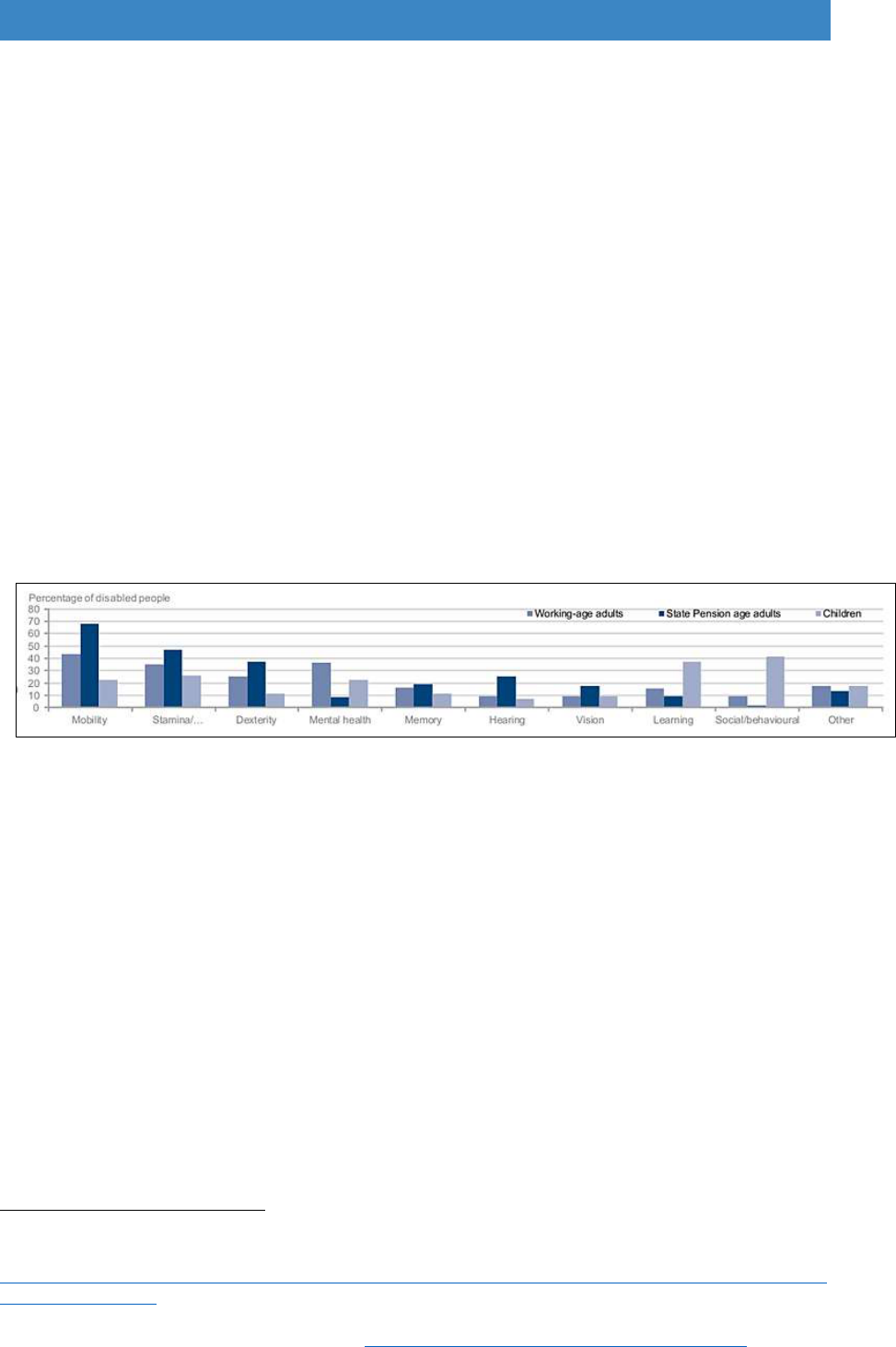

4.4 These proportions reflect broader trends in levels of disability in the UK, with a

rise in the number of children and working age adults with impairments. Medical

advances are enabling disabled children to live longer lives and helping more

people survive illness and accidents (Figure 4.2). There is a predominance of

disabled boys in childhood, while women are slightly more likely to be disabled

than men as people age. There is high proportion of disabled women in the later

stages of life due to their longer life expectancy (Figure 4.3).

Figure 4.2 Disability prevalence by age group 2006/07 to 2016/17

Source: Department of Work and Pensions (Mar 2018) Family Resources Survey 2016/17, Table 4.1.

Note: figures are for the UK.

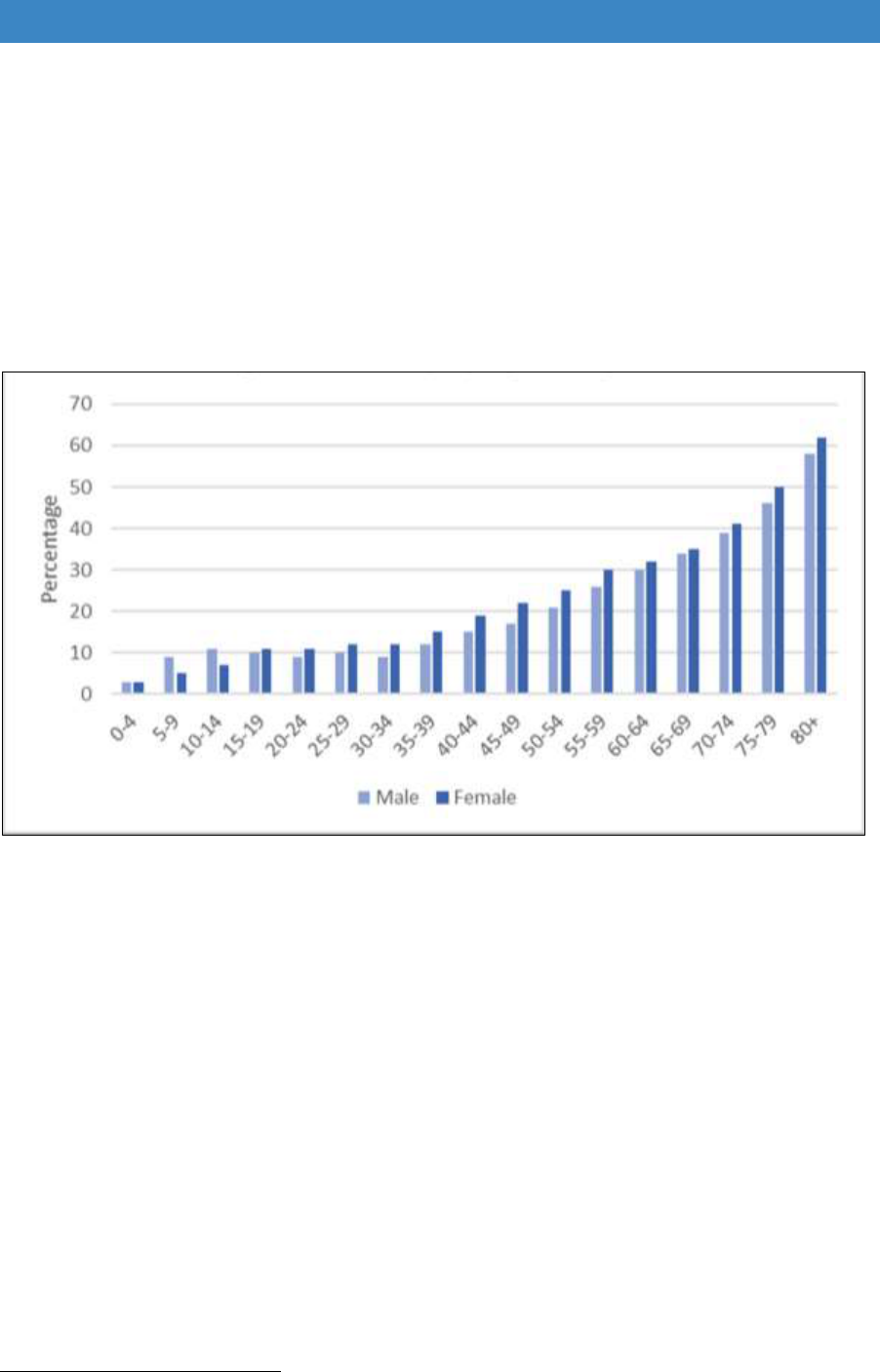

Figure 4.3 Prevalence of disability by age and gender UK

Source: Family Resources Survey 2016/17 Table 4.3 - average of 2014/15-2016/17

28

Disabled Facilities Grant (DFG) and Other Adaptations: Main Report

4.5 Higher numbers of older people are likely to get DFG funding in any year due to

the substantial rise in the proportion of people with impairments as people reach

their 70s and 80s (Figure 4.4). The preventative role of adaptations in helping

people before they reach crisis point needs to be addressed. Services also need

to reflect the fact that many of those needing help will be on their own. The

English Housing Survey shows that in 2014/15 47% of those aged 75-84 and

61% of those aged 85 and over were living alone

14

. Many of those will be single

women.

Figure 4.4 Disabled people by age UK

Source: Family Resources Survey 2016/17 Table 4.3

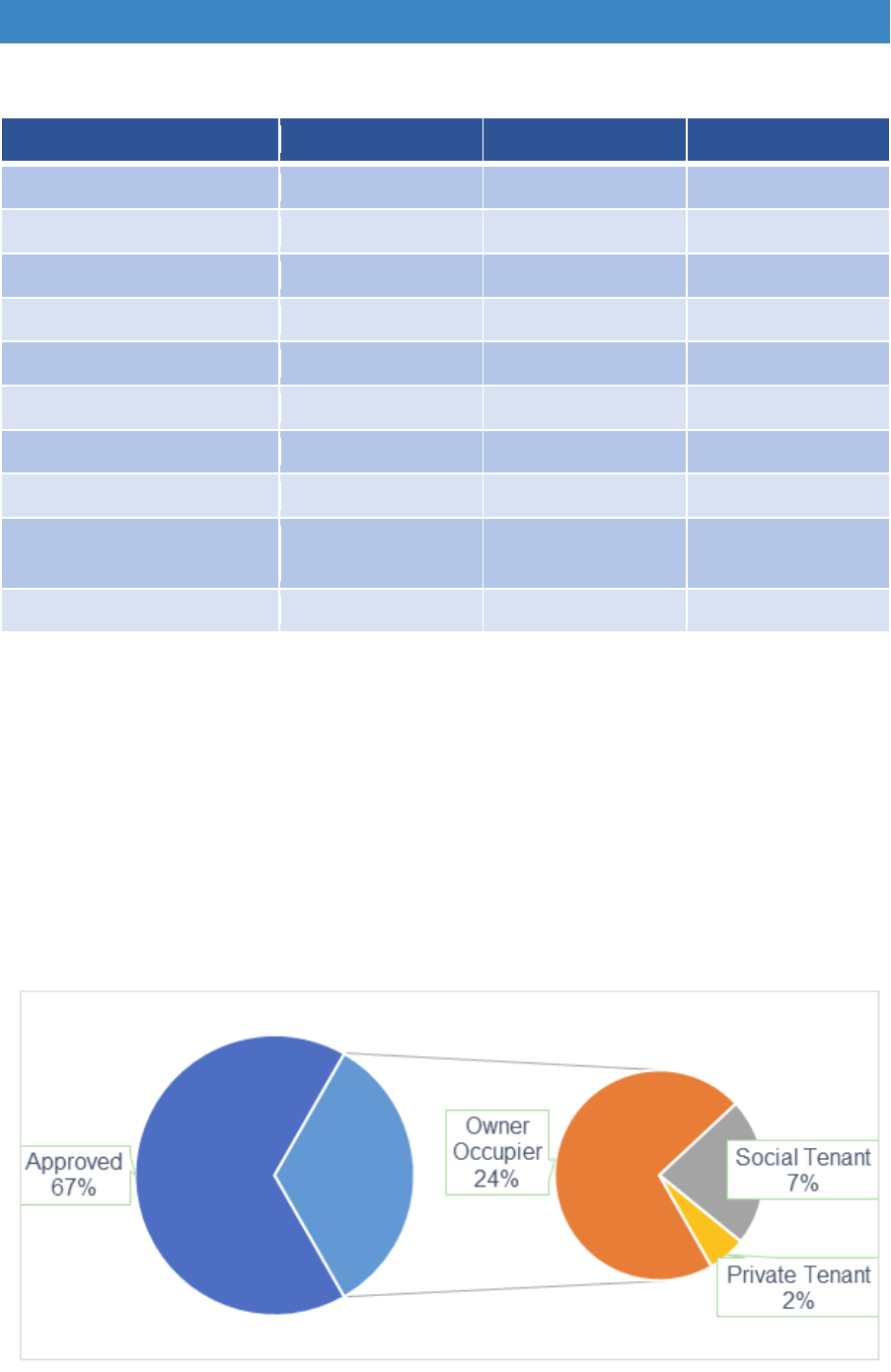

Tenure of DFG recipients

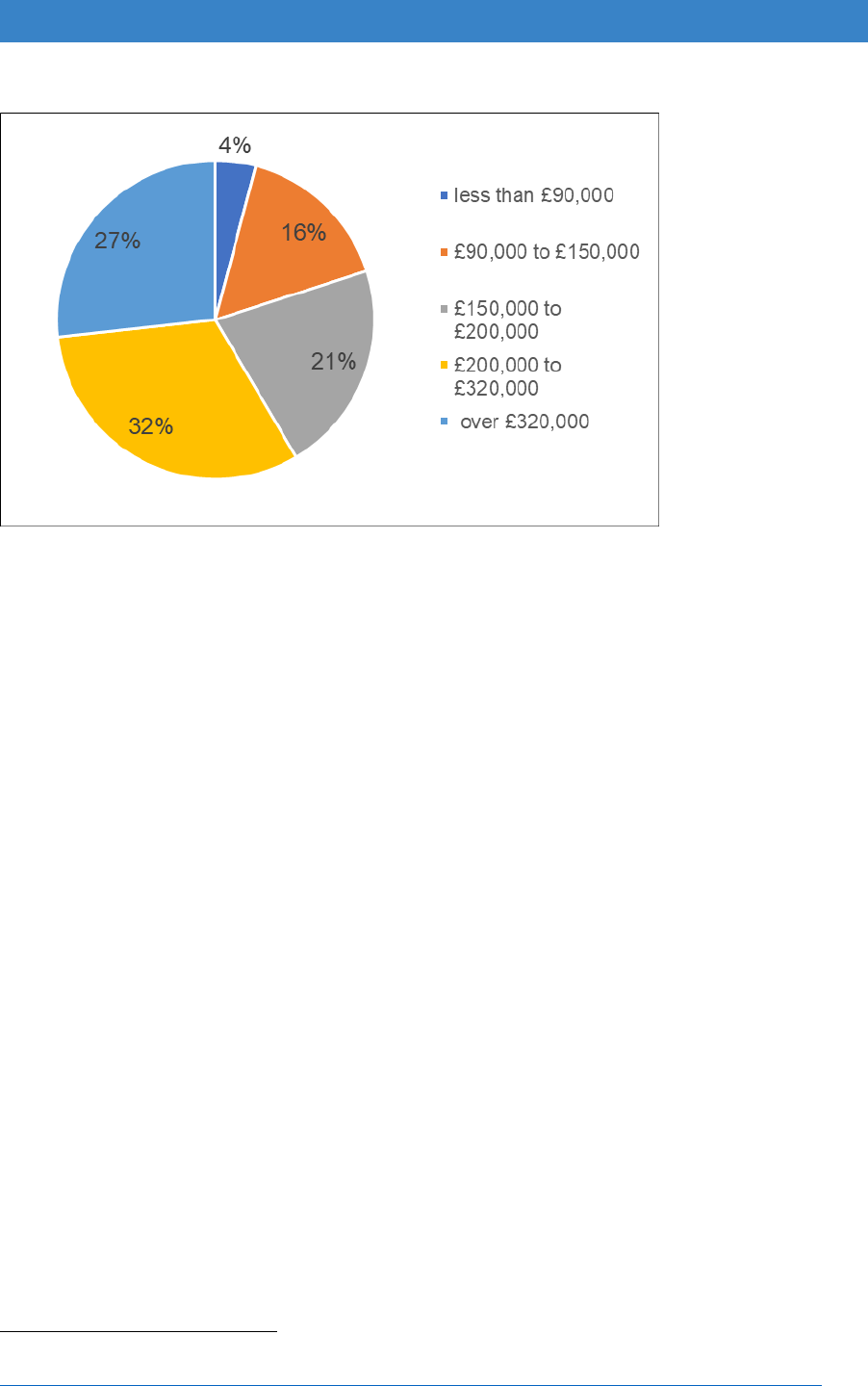

4.6 It is useful to look at who gets the grant by tenure, and the likely future trends, to

see how this might affect grant allocations and the delivery process. Applicants

for DFG funding can be owners, those renting privately and tenants of registered

providers, but not council tenants. Landlords are allowed to apply directly on

behalf of their tenants.

Home owners

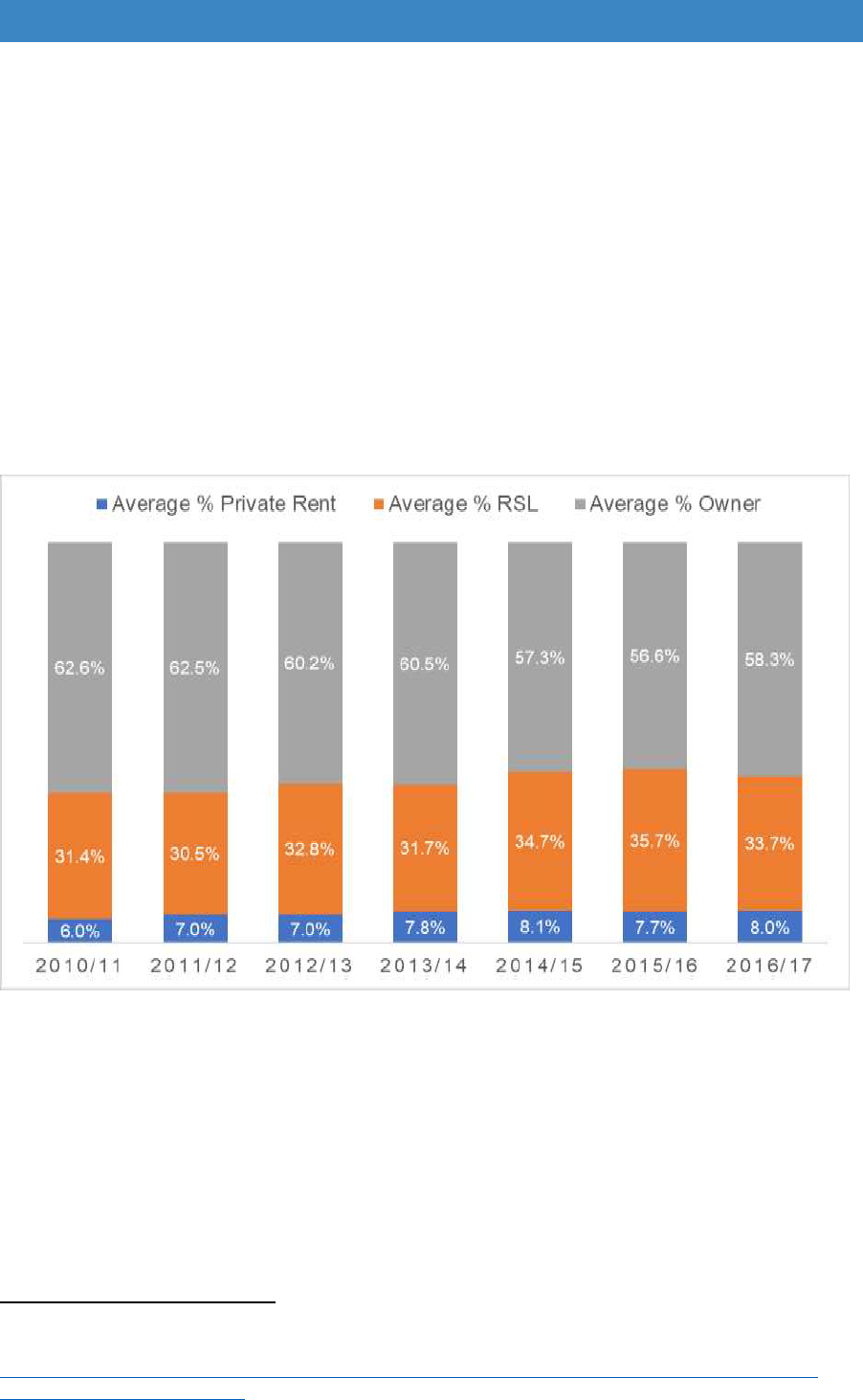

4.7 Home owners on low incomes have always been the biggest recipients of DFG

funding as the grant mostly goes to older people, and 76% are home owners. In

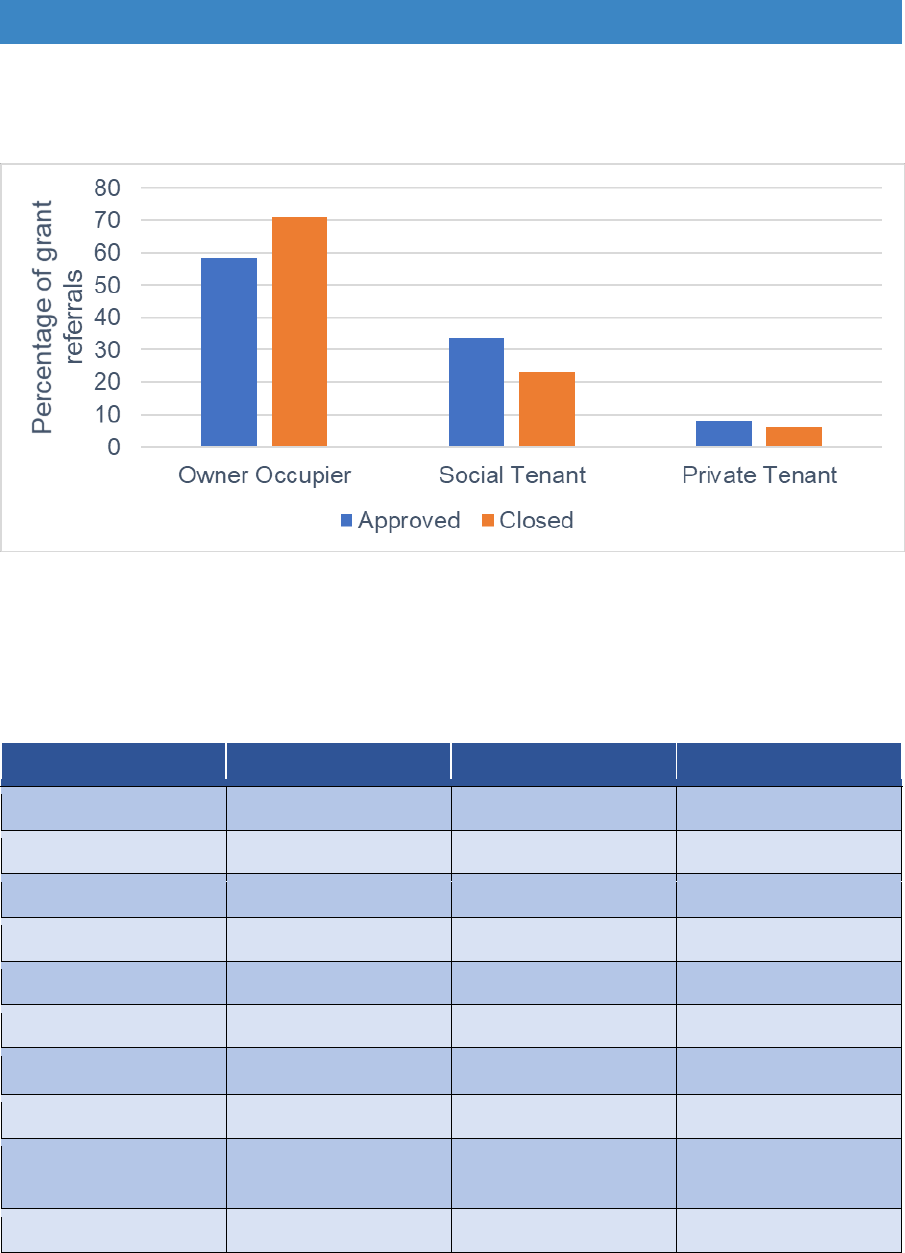

2016/17, 58% of grants went to home owners but there has been a slight

decrease in the proportion going to this tenure since 2010/11 (Figure 4.5). It is

14

Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (2016b) English housing survey 2014 to

2015: Housing for older people report, ibid.

29

Disabled Facilities Grant (DFG) and Other Adaptations: Main Report

an optimistic sign that in the English Housing Survey over half (55%) of

households over 75 that required adaptations in their home said that they already

had them installed (although there was no independent check on the quality or

appropriateness of these adaptations)

15

. There has been a lot of investment in

the owner-occupied stock over the last 30 years, with showers and wet rooms

seen as desirable features which may start to reduce the need for the

replacement of baths.

4.8 However, the English House Condition Survey shows that people over 65 are

still by far the biggest group requiring adaptations. Home ownership is also

common in the cohort approaching retirement and as the population continues

to age, grants for older home owners will continue to dominate DFG allocations.

Figure 4.5 Trends in tenure of DFG recipients

Source: LOGASnet

Registered providers

4.9 A third of grants go to tenants of registered providers. Many disabled people are

in this sector as they tend to have lower incomes and cannot afford home

ownership. However, registered providers only hold between 5 and 15% of the

housing stock in any local authority area. From previous research, areas where

15

Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (2016a) English housing survey 2014 to

2015: Adaptations and accessibility of homes report, London: MHCLG.

https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/english-housing-survey-2014-to-2015-adaptations-and-

accessibility-of-homes-report.

30

Disabled Facilities Grant (DFG) and Other Adaptations: Main Report

stock has been transferred have a higher proportion of grants going to registered

providers than those with retained council stock

16

.

4.10 Registered providers’ use of the DFG seems disproportionate as their housing is

newer on average, with a higher proportion of accessible homes. It is probably

because registered provider tenants have a clear route. They are signposted

directly to the DFG with some landlords applying on their behalf. In contrast,

home owners and private tenants have very few ways of finding out about the

grant, as it is seldom advertised and not easy to find on local authority websites.

Private rented sector tenants

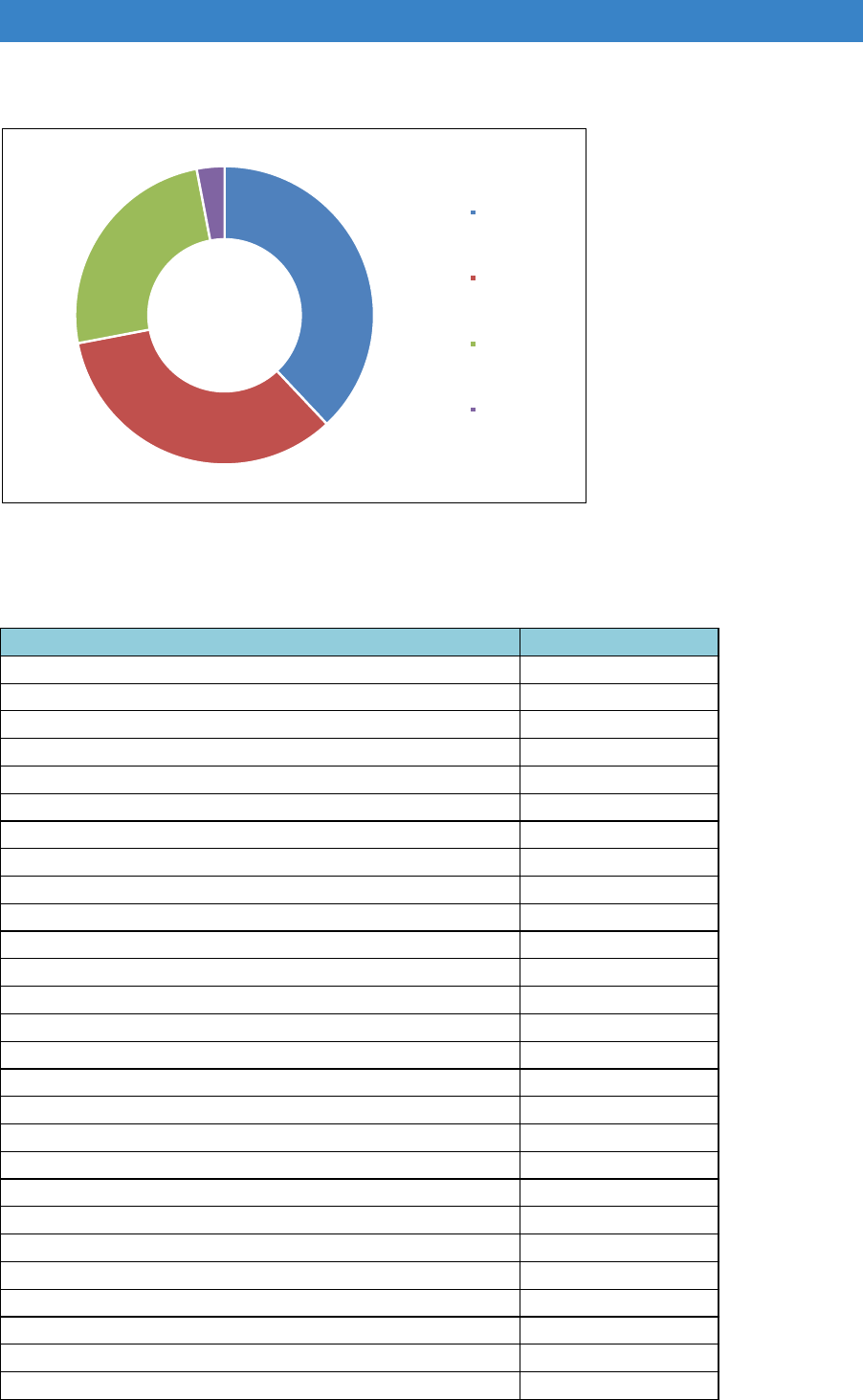

4.11 Private renting is becoming increasing common and the share of grants going to

this sector is inevitably going to continue to rise, particularly for younger age

groups. However, one in four privately rented dwellings do not meet the Decent

Homes standard and they are more likely than other tenures to have Category 1

hazards such as excess cold or risk of falls

17

. One in three disabled private rented

sector tenants feels that their home does not meet their needs, which is higher

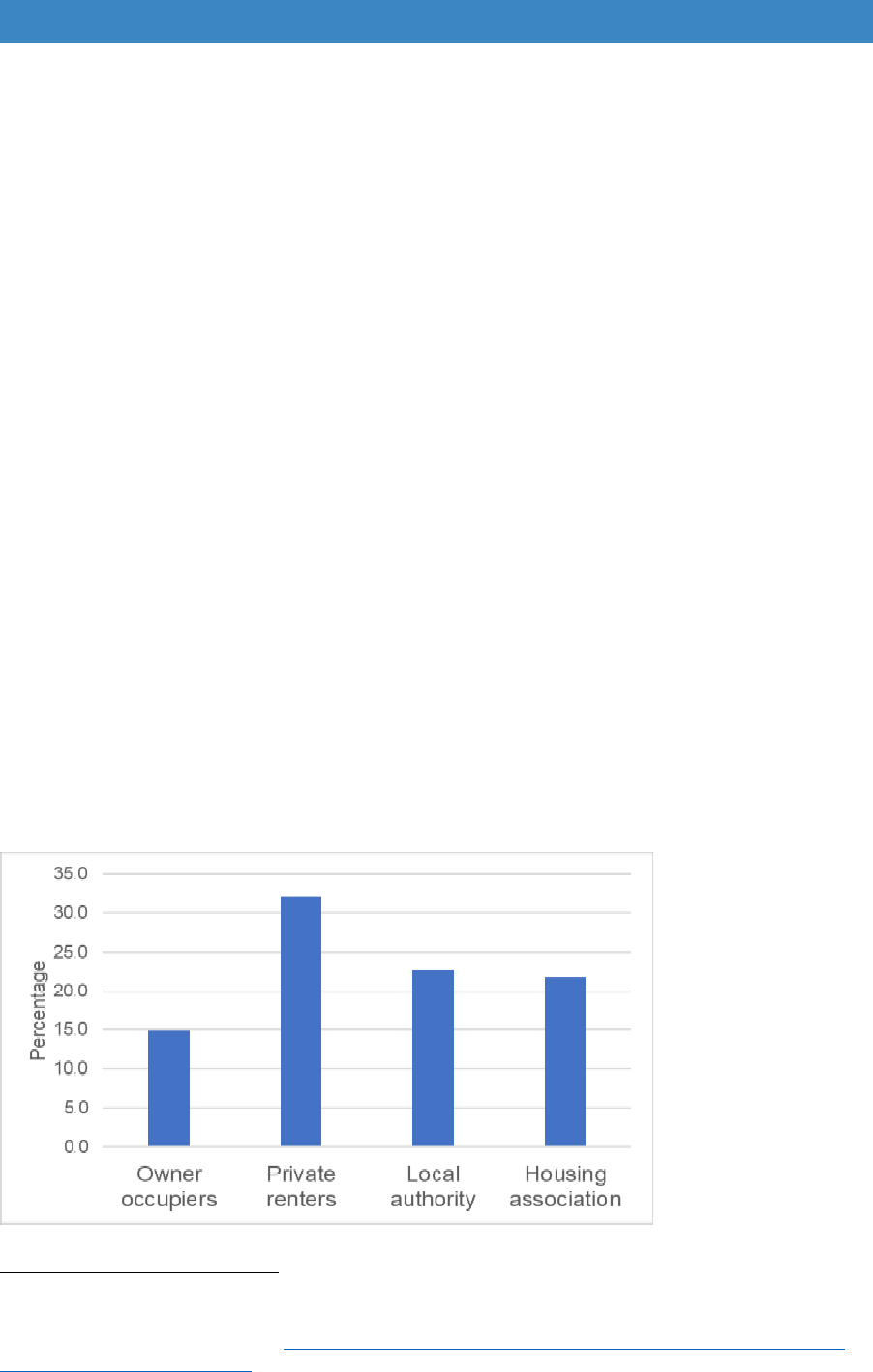

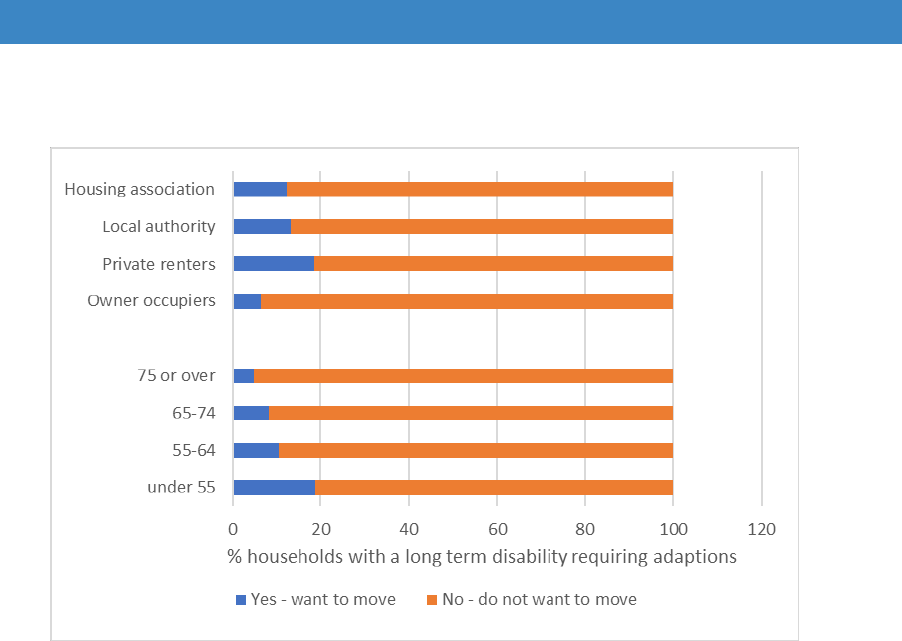

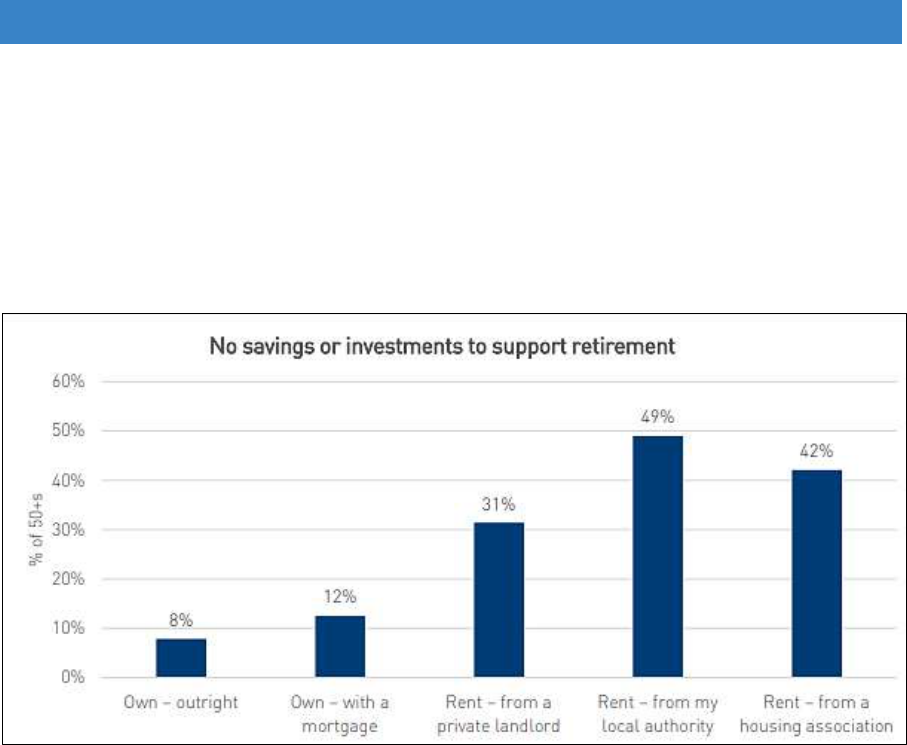

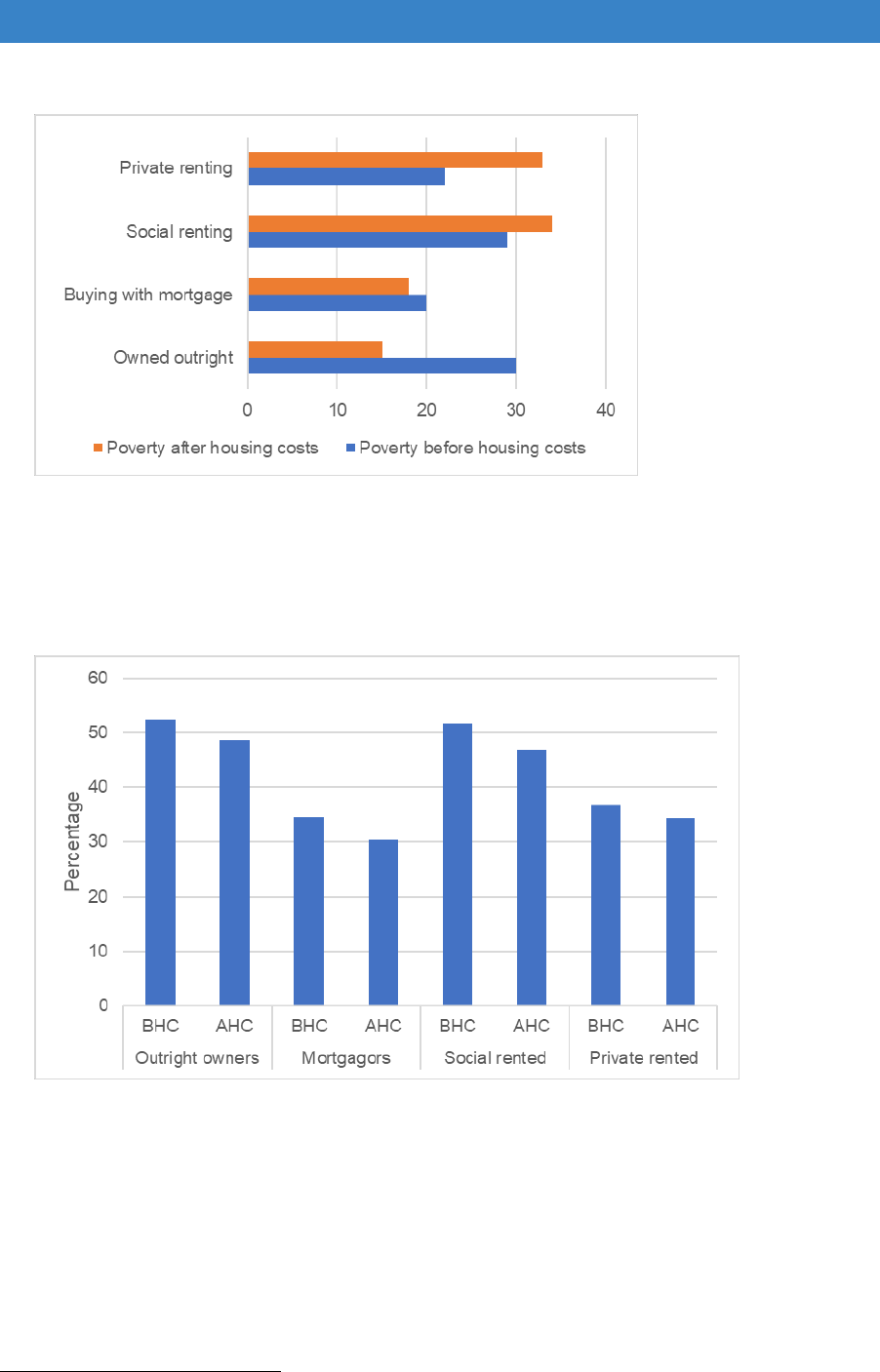

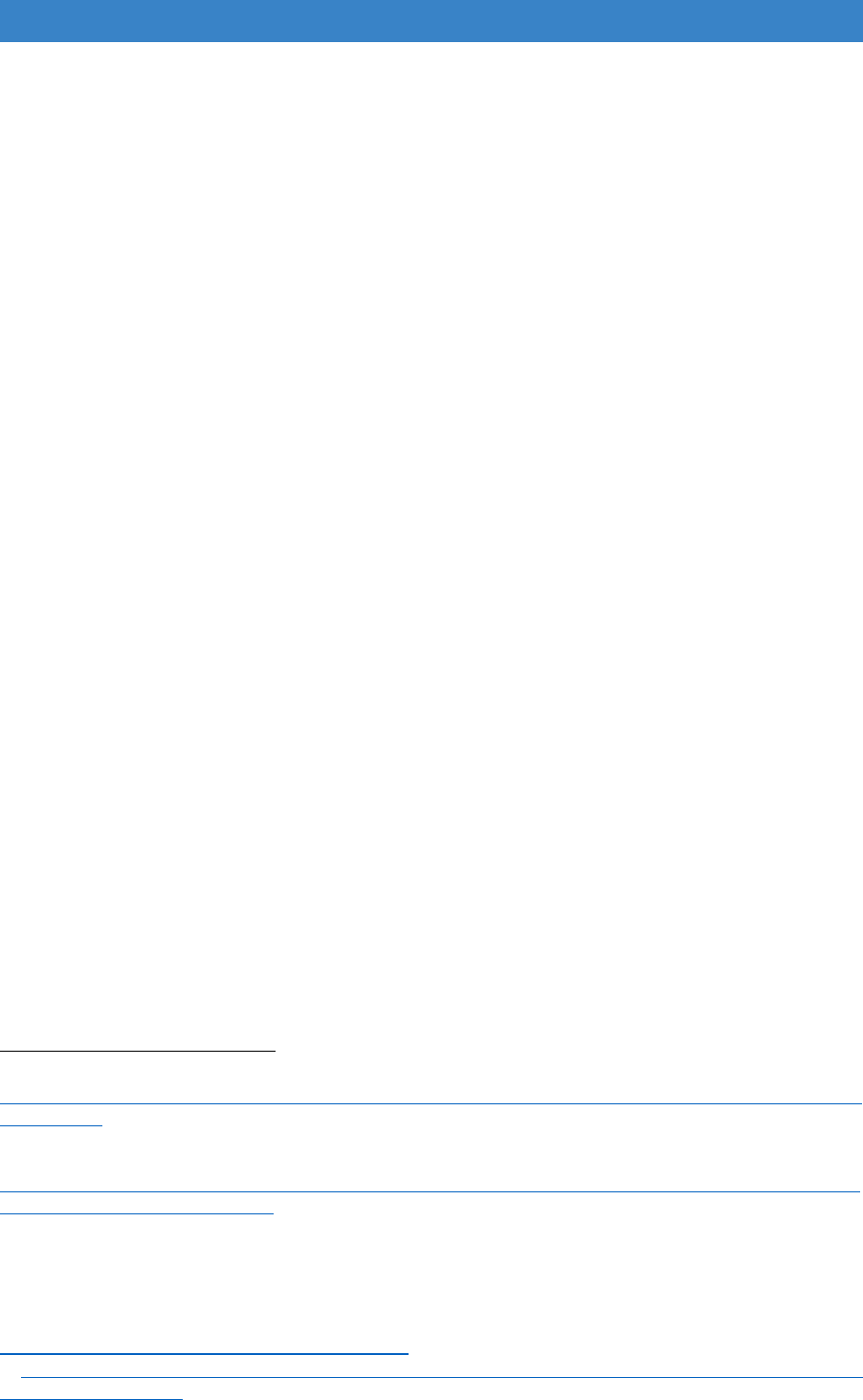

than any other tenure (Figure 4.6)

18

.

4.12 There are now almost as many disabled households in the private rented sector

as renting from registered providers (Figure 4.7). Although they are worse

housed, they get a fraction of DFGs (8%) compared to registered providers

(34%).

Figure 4.6 Unsuitable accommodation by tenure 2014-15

Source: MHCLG (2016) English Housing Survey, Table 1.3

16

Mackintosh S. and Leather P. (2016) ibid.

17

Department of Communities and Local Government (Mar 2018) English Housing survey: Headline

Report 2015/16, London: DCLG. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/english-housing-survey-

2015-to-2016-headline-report.

18

Department of Communities and Local Government (2016a) English Housing survey: 2014 to 15,

Adaptations and accessibility of homes report, ibid.

31

Disabled Facilities Grant (DFG) and Other Adaptations: Main Report

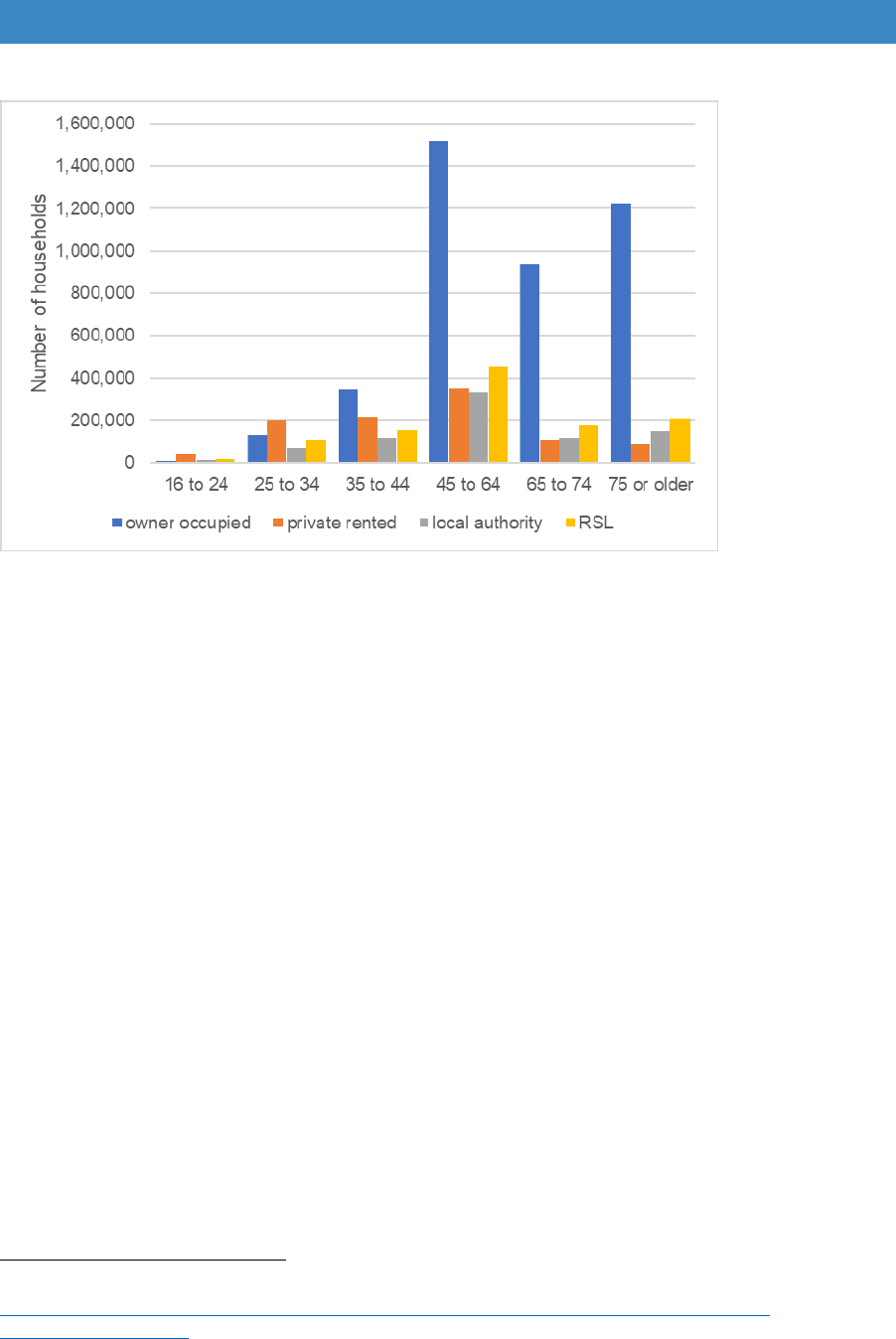

Figure 4.7 Number of households with long-term limiting illness by age and tenure

Source: English Housing Survey 2014-15, full household sample

4.13 Most households with long-term limiting illness are of working age. Increasingly

they are in private rented homes as it becomes harder to get into social housing

or on to the home ownership ladder. The focus of government policy is on getting

as many disabled people as possible into work, but this is difficult if the home is

not accessible, lacks level access to the street outside, or does not facilitate

home working.

4.14 There are now more children in the private rented sector than in social housing

19

.

Households with dependent children rose from 30% of all privately renting

households in 2005-06 to 36% in 2015-16 and half a million (510,000) children

live in privately rented homes that are unsafe. Research has shown that disabled

children tend to be the worst housed of any age group

20

. They also tend to spend

a lot of time at home and are often very isolated, meaning the accessibility and

quality of the home assumes even greater importance

21

.

4.15 Despite the rise of families in the tenure, the private rental sector remains an

insecure place to live

22

. A third (34%) of private renters have lived in their current

home for less than a year, and two thirds for less than three years (67%).

4.16 Until recently, the number of older people in the private rented sector was low. In

2014-15, households over 65 made up just 8.5 per cent (360,000) of all those

19

Parker, I. and Isaksen, M. (2017) A state of disrepair: Why renters deserve a better deal.

https://www.citizensadvice.org.uk/Global/CitizensAdvice/Housing%20Publications/PRS-

AStateofDisrepair.pdf.

20

Beresford, B. and Rhodes, D. (2008) Housing and disabled children, York: Joseph Rowntree

Foundation.

21

Contact a Family (2011) Forgotten Families: The impact of isolation on families with disabled

children across the UK, London: Contact a Family.

22

Parker and Isaksen (2017) ibid.

32

Disabled Facilities Grant (DFG) and Other Adaptations: Main Report

renting privately

23

. However, there is a diversity of supply and tenancy

arrangements, with some older tenants living in very poor conditions

24

. Numbers

of older people in this sector will begin to increase in the 2020s as higher

proportions are in the cohorts approaching retirement age (Figure 4.7 above). A

survey in 2016 for Citizens Advice revealed that 40% of people aged 55-64 and

34% of those over 65 renting privately have a tenancy that lasts six months or

less

25

. As numbers in this tenure increase, for a significant proportion, it may

become difficult to age in place successfully.

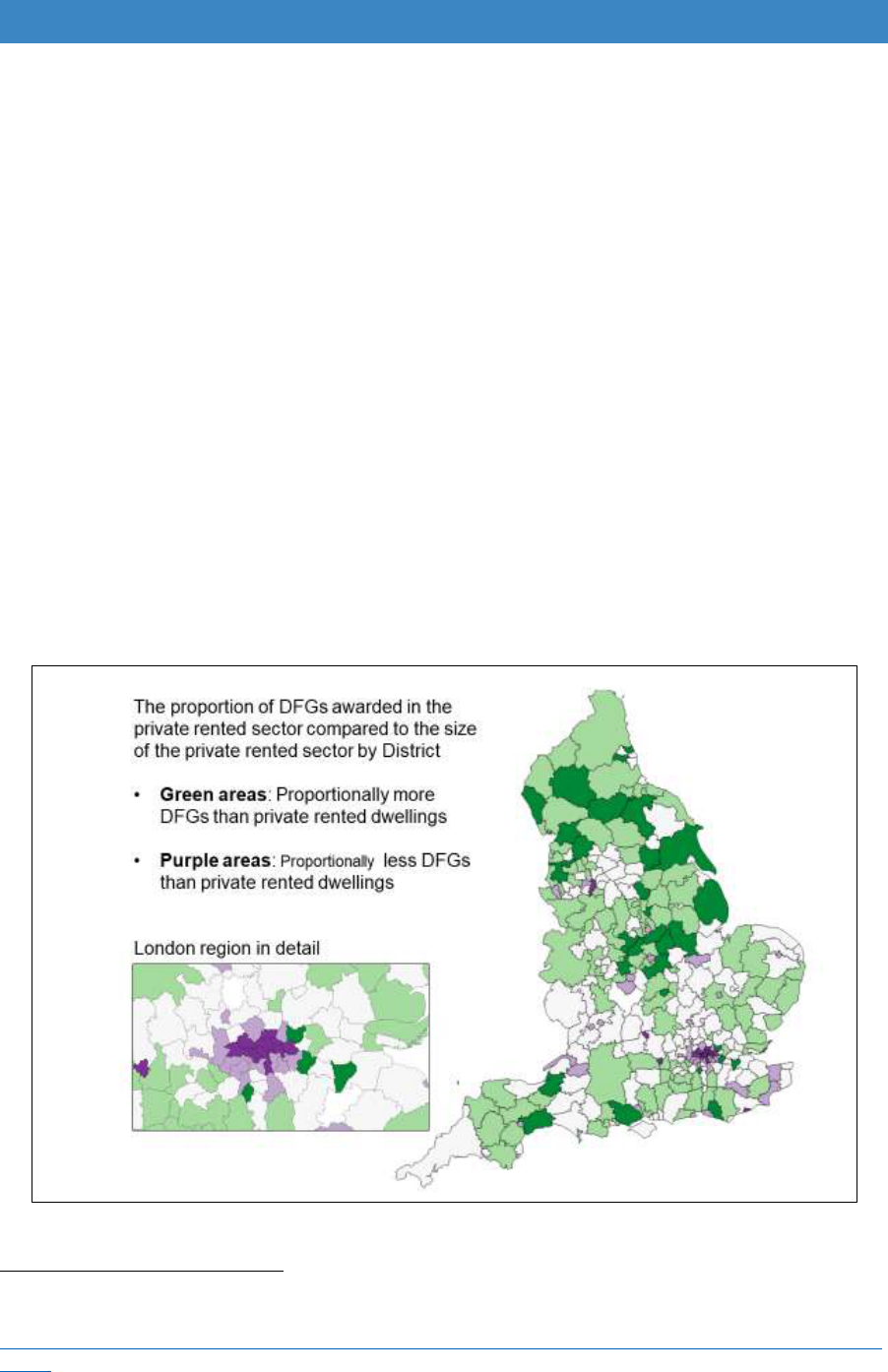

4.17 There are problems delivering the DFG in this tenure. Grants are difficult to

approve if the home is in poor condition, but in many areas of the country

alternative accommodation is not easy to find at a price people can afford. Short-

term tenancies also have a major effect on DFG approvals as residents are

supposed to show they plan to remain for at least five years. In addition, landlords

may not always give permission for the necessary changes to the property. Parts

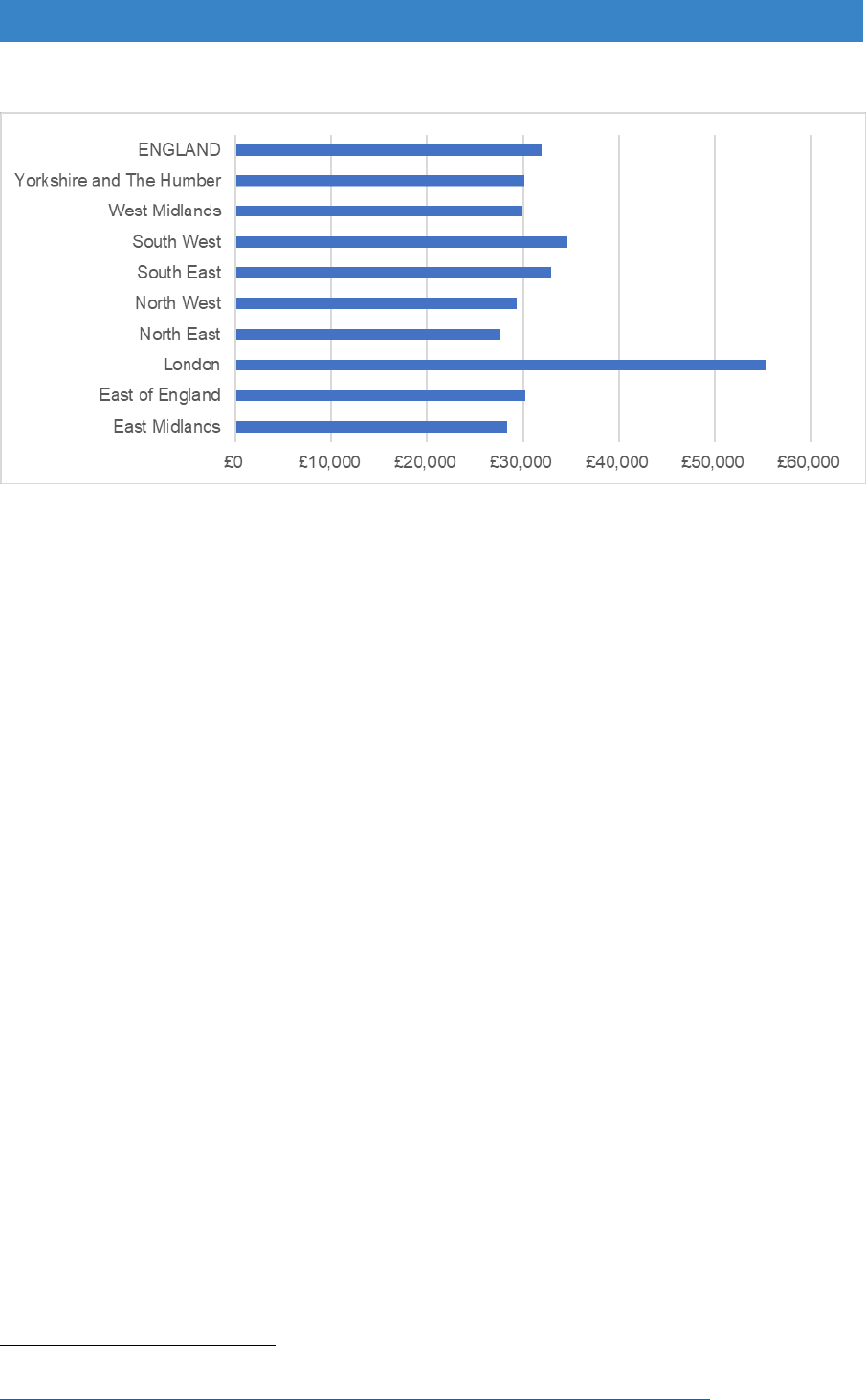

of the country with high proportions of private renting, such as central London,

appear to be getting fewer grants than might be expected, probably because of

these reasons (Figure 4.8).

Figure 4.8 Distribution of DFGs in the private rented sector

Source: LOGASnet

23

Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (2016c) English Housing Survey 2014 to

2015: Private Rented Sector report, London: MHCLG.

https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/english-housing-survey-2014-to-2015-private-rented-sector-

report.

24

Rugg, J. and Croucher, K. (2010) Older People’s Experiences of Renting Privately, London: Age

Concern and Help the Aged.

25

Parker and Isaksen (2017) ibid.

33

Disabled Facilities Grant (DFG) and Other Adaptations: Main Report

Council stock

4.18 The main DFG budget cannot be used to fund adaptations to local authority

properties

26

. Council landlords are expected to use their own resources from the

local authority Housing Revenue Account (HRA). Additional funding was

included for disabled adaptations in self-financing determinations from 2012

27

.

Compared to registered providers, council tenants tend to be older, and the stock

was built at an earlier date.

4.19 How funding levels and delivery processes differ using the HRA relative to the

DFG is outside the remit of this review. However, if more stock is transferred and

becomes eligible for the DFG, account will need to be taken of this in the national

allocation of resources. A FOI in 2017 to 176 authorities with more than 100 units

of retained stock was returned by 76% of authorities (80% of those with

significant amounts of stock). This showed that the majority were using the HRA

(91%). Those that were not using the HRA were all Arms-Length Management

Organisations (ALMOs). It is hoped that they have their own budgets for

adaptations, but some may be using the DFG.

4.20 Whichever funding source is used to access assistance with home adaptations

(DFG or HRA), it should be tenure neutral with all applicants given equal access

to funding. In some areas, local adaptation teams handle council stock

modifications alongside DFG work, making it easier to apply to apply the same

standards.

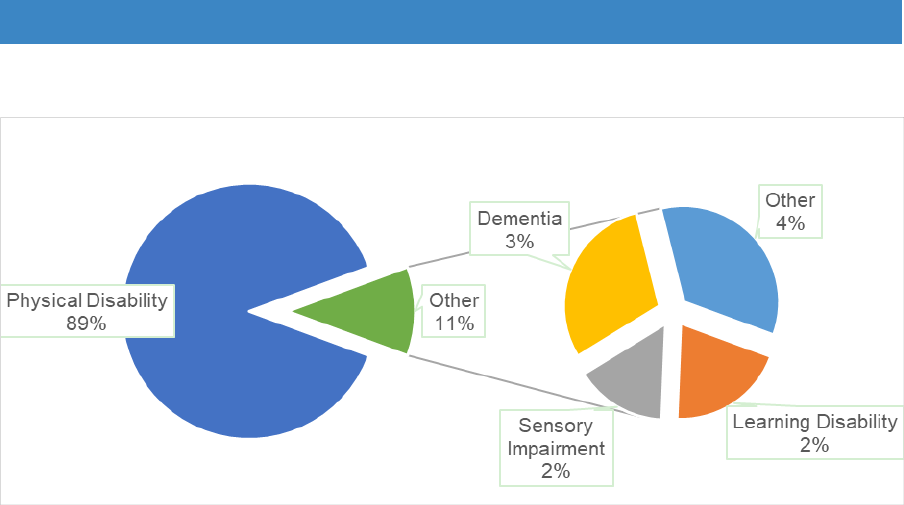

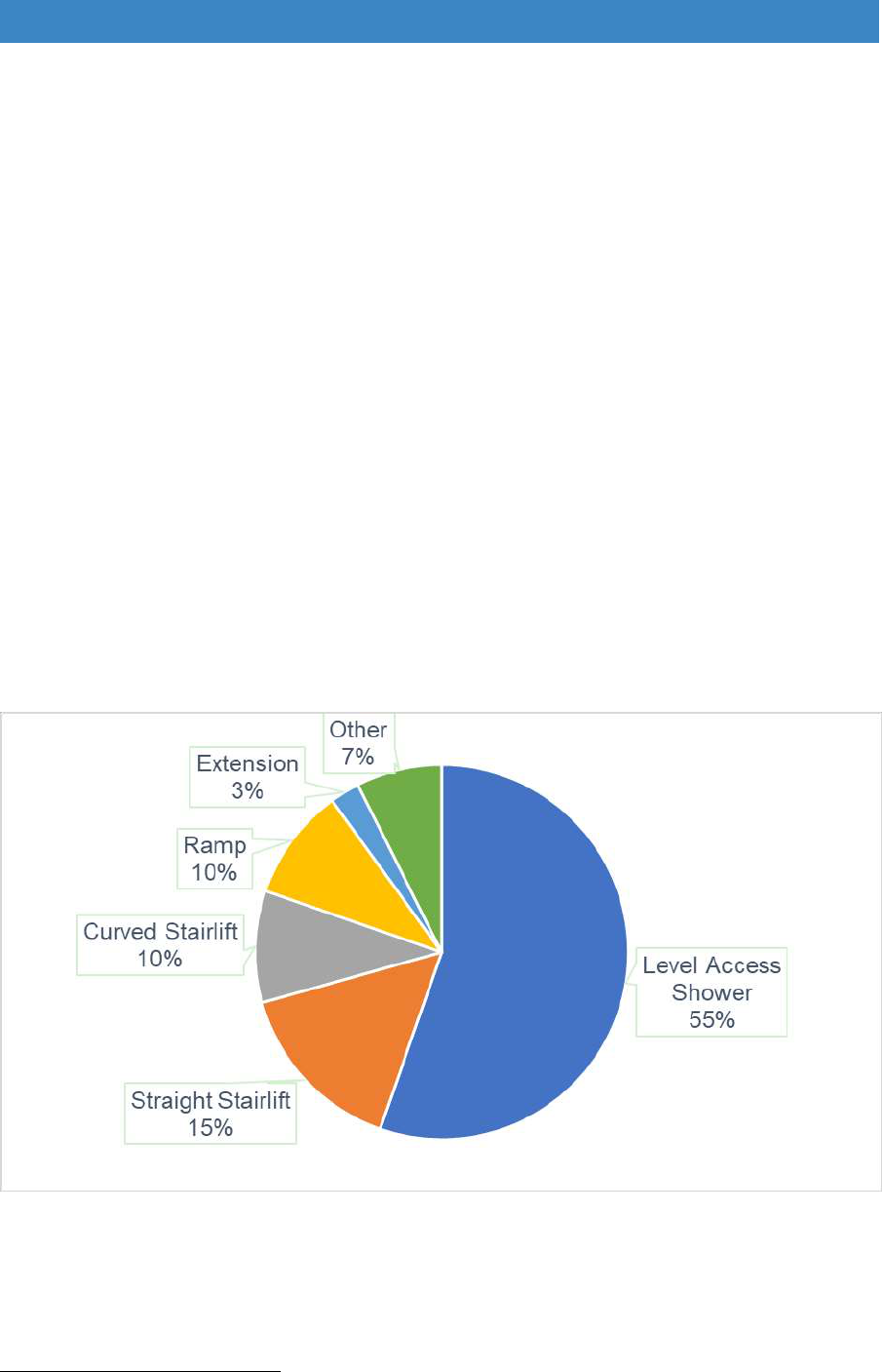

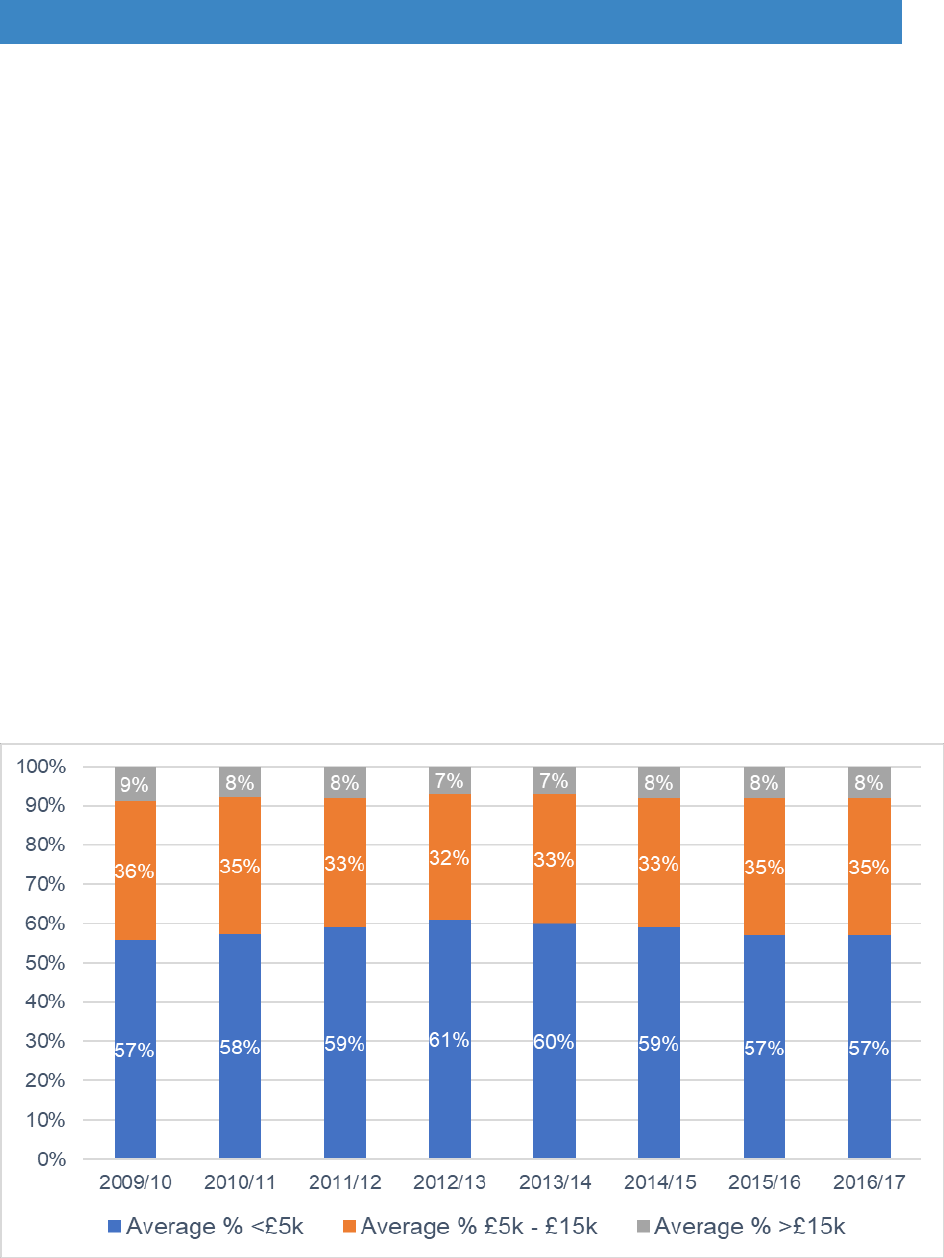

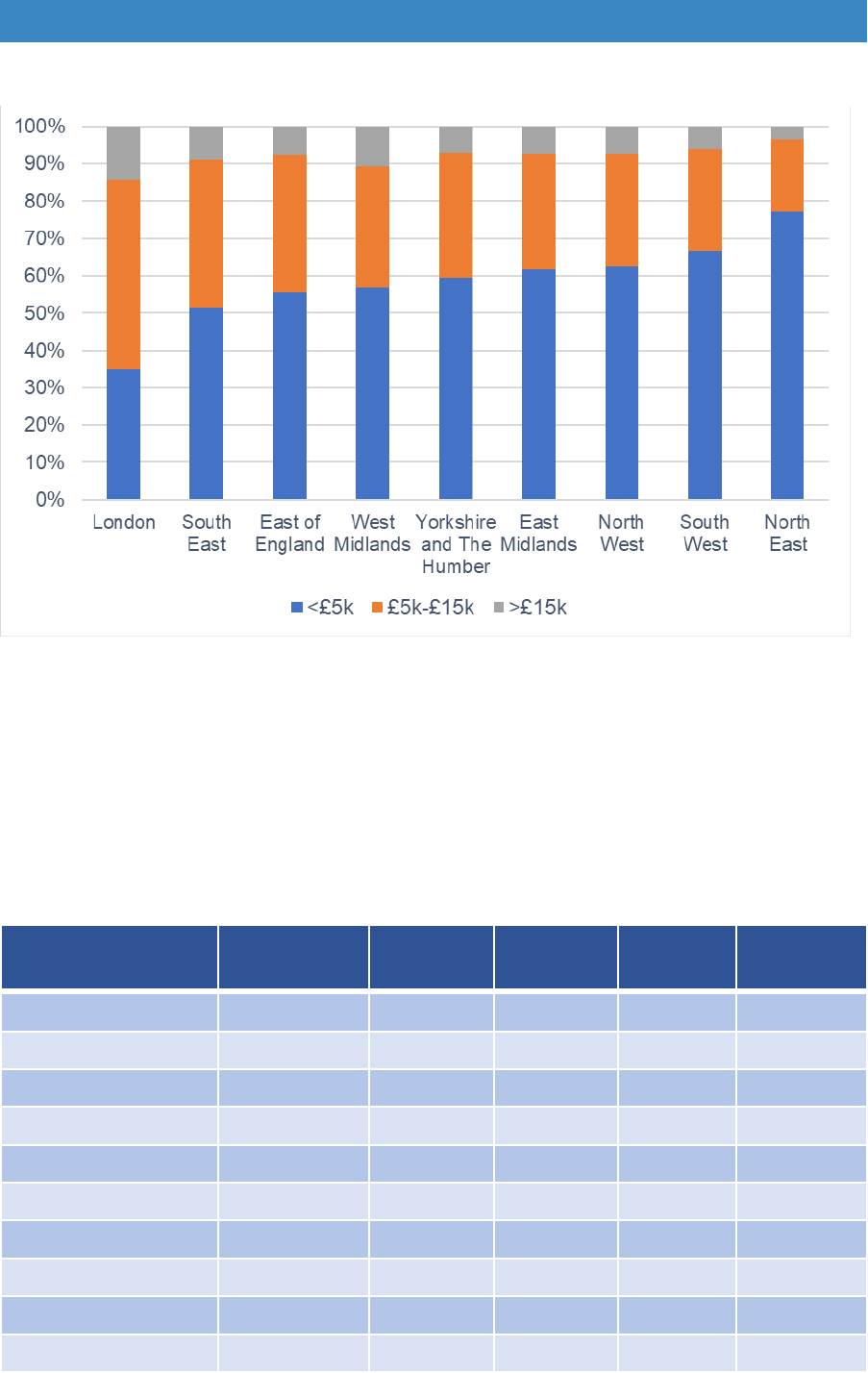

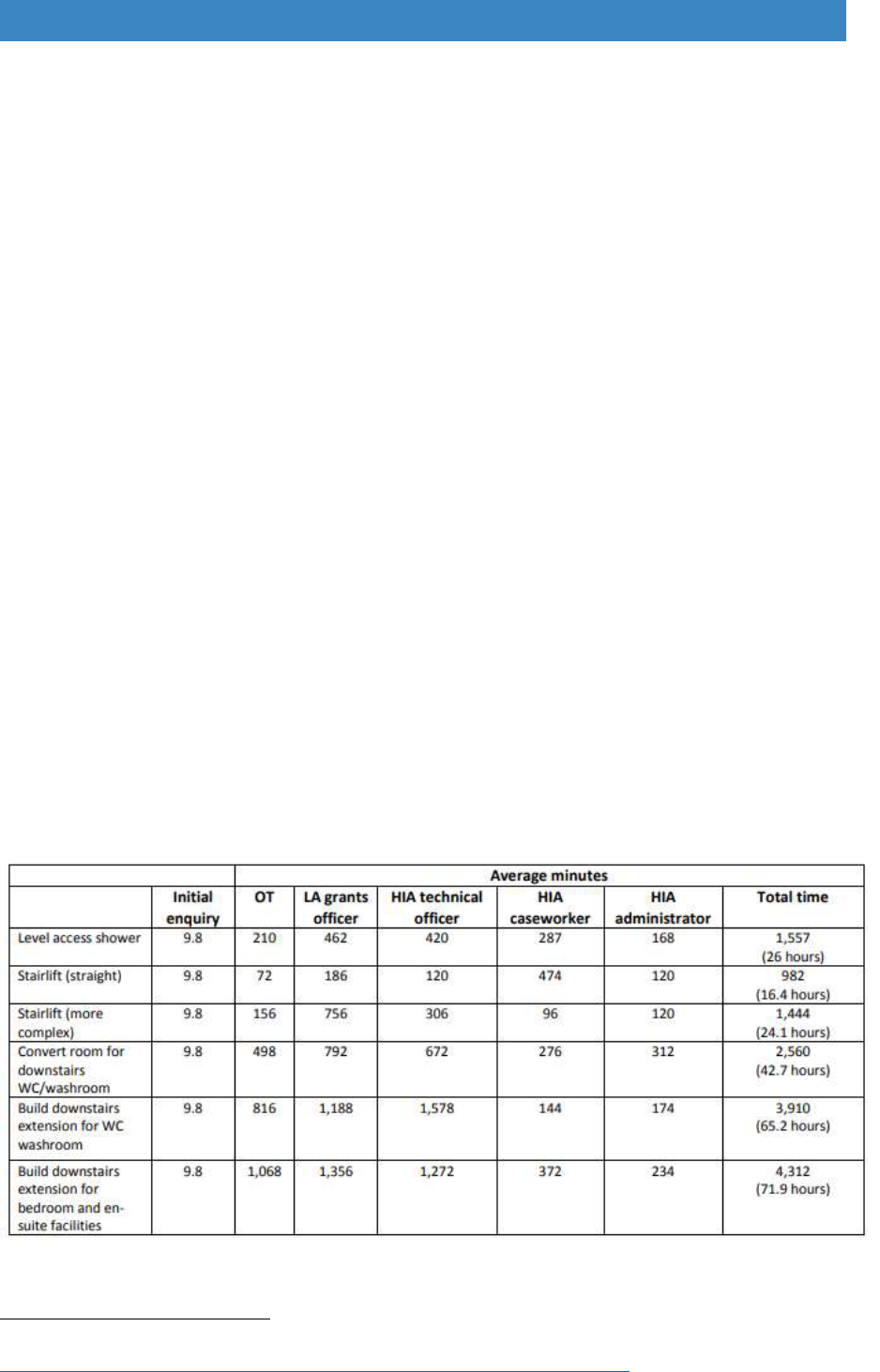

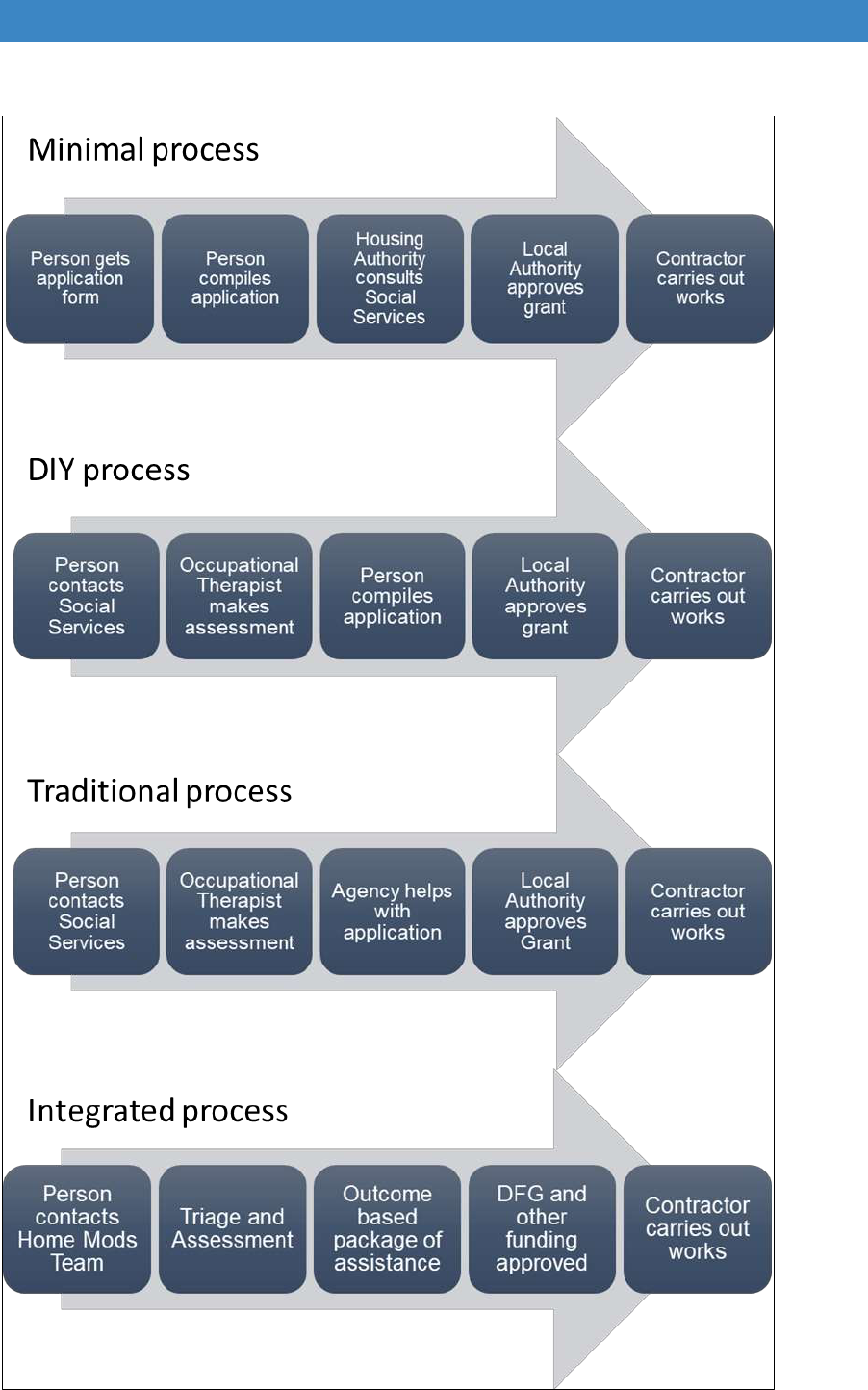

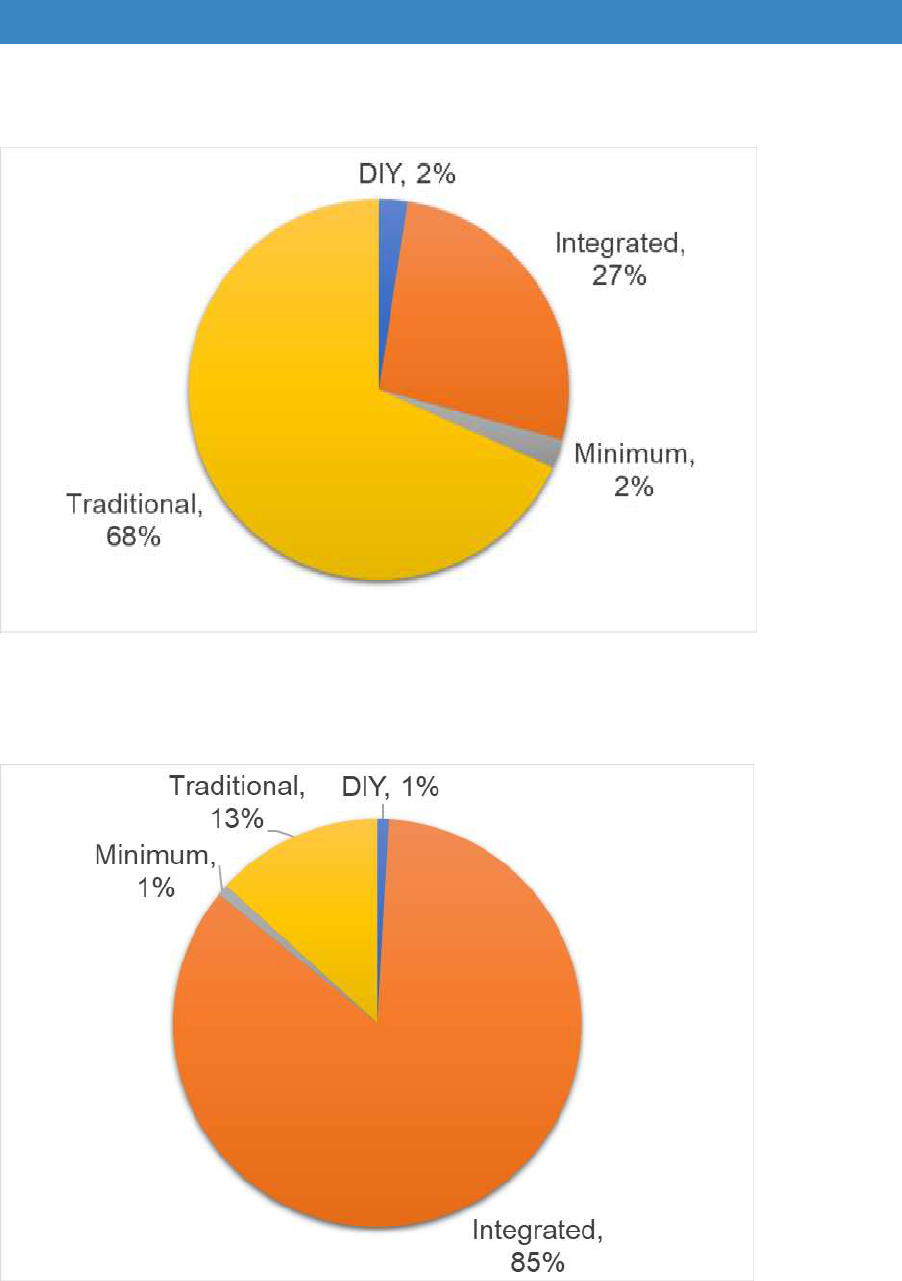

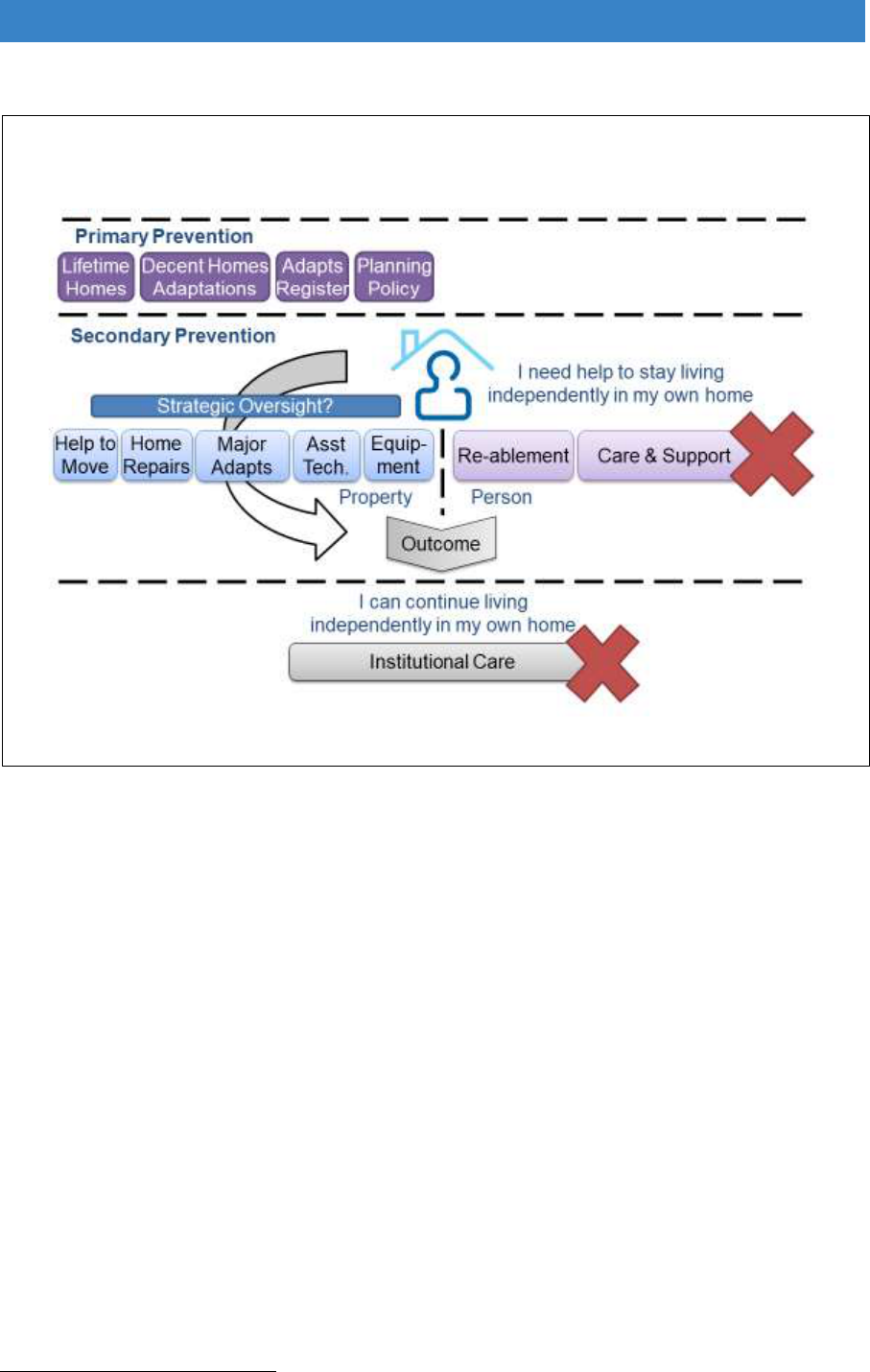

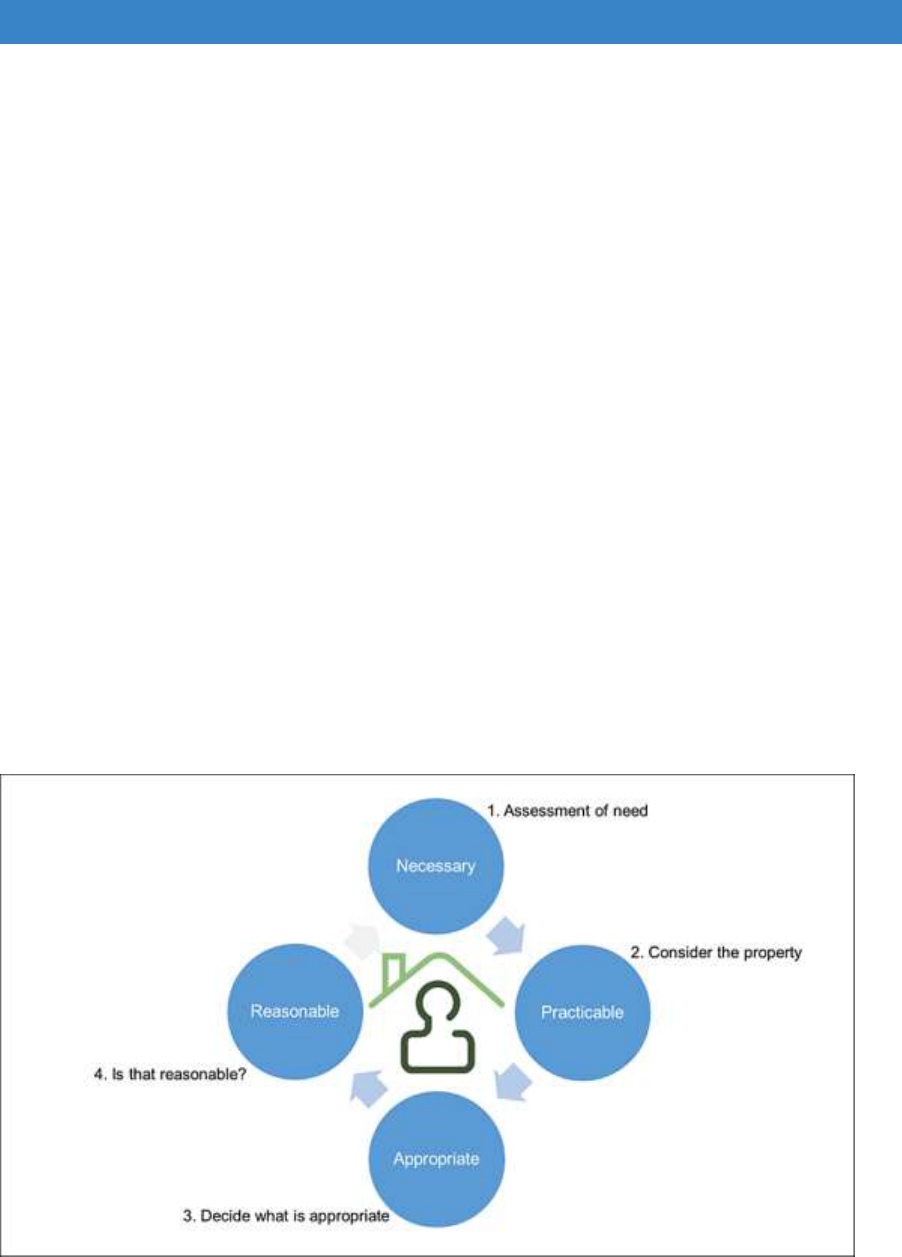

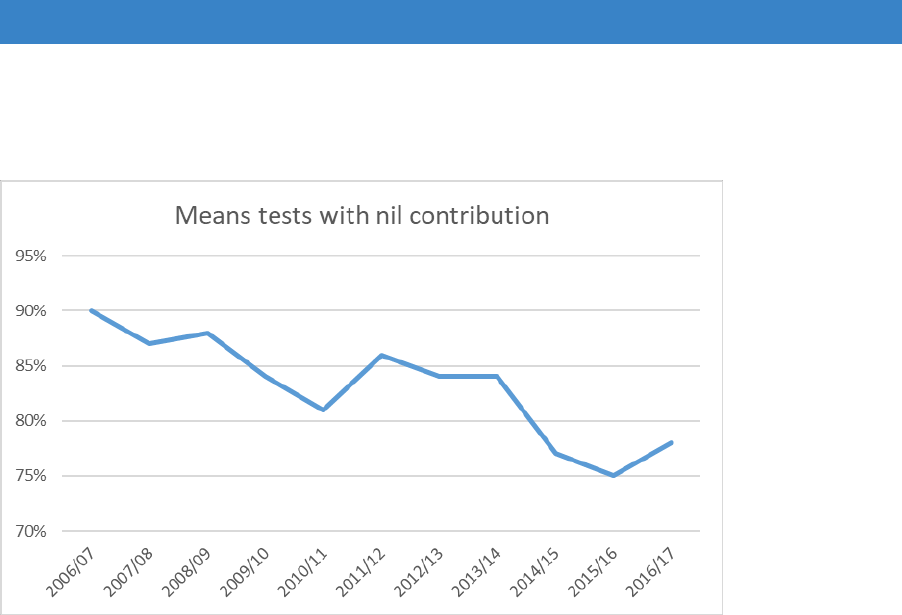

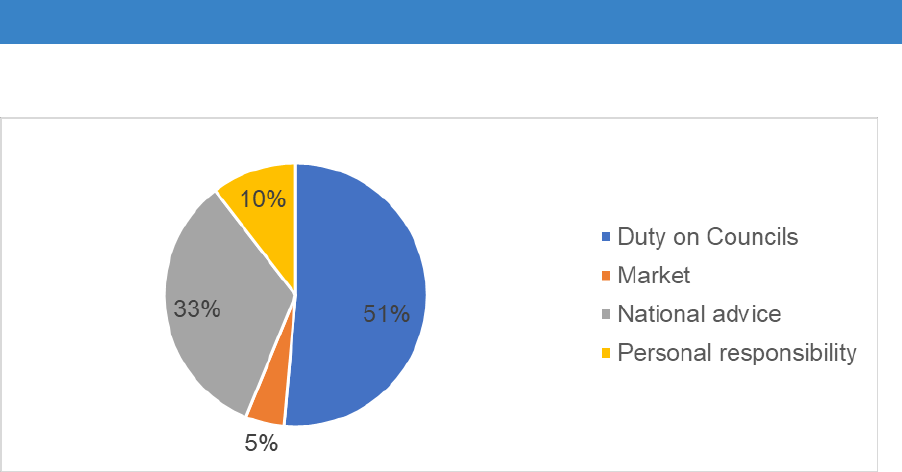

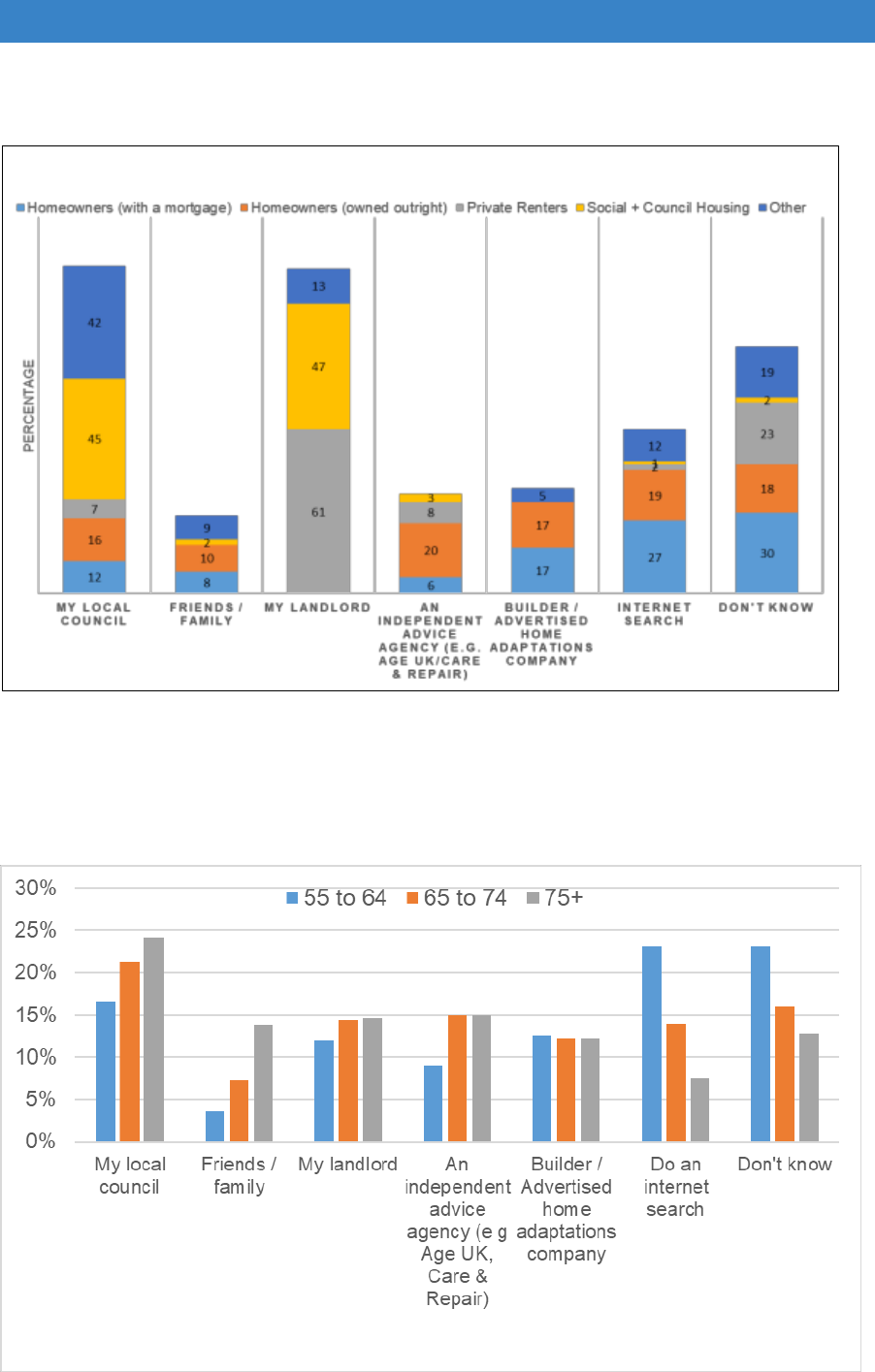

Rural housing